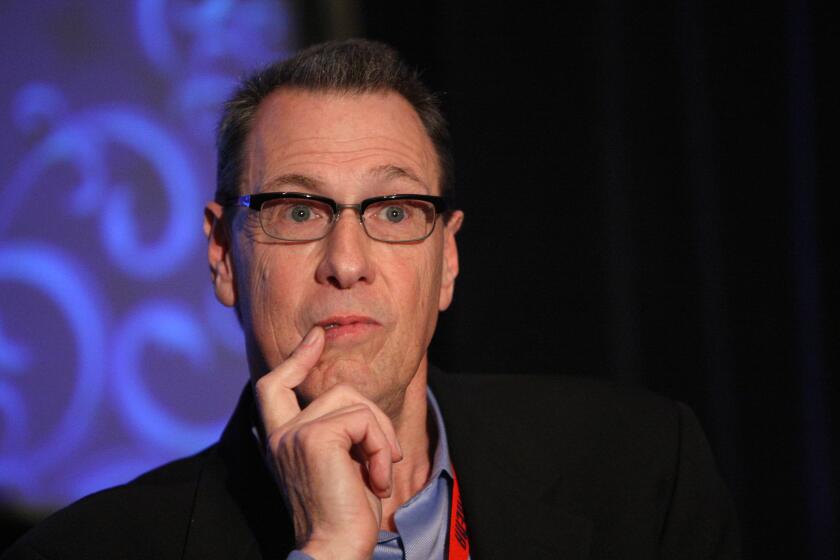

Andrew Kay dies at 95; inventor pioneered compact computers

For a few years in the 1980s, Andrew Kay’s computers were top-quality, low-cost and, for the day, feather-light.

The Kaypro II, one of the top-selling “portables” in America, weighed in at a mere 26 pounds. While elephantine by today’s standards, it was a favorite of early computer aficionados and Kay became, albeit briefly, a high-tech titan. By 1990 he had filed for bankruptcy protection.

Kay, a charismatic inventor who scoffed at traditional management techniques and gave his factory workers and salespeople an unusual degree of freedom, died Aug. 28 at an assisted living home in Vista. He was 95.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Andrew Kay obituary: In the Sept. 11 LATExtra section, the obituary of personal computing pioneer Andrew Kay said that he and his wife, Mary, who died in 1996, were married for 66 years. They were married for 56 years. —

------------

His death from ailments related to old age was confirmed by his son David.

Kay, who grew up speaking an Eastern European dialect called Lemko, believed in the power of an improved vocabulary and always encouraged employees to build their word skills. Enthused by the human potential movement of the 1960s, he took frequent trips to Esalen with his wife and four children, and tried to apply some of the movement’s precepts at work.

“People grow through learning and I guess that is what I tried to do in my factory,” he said years later.

At Kay’s plant in Solana Beach, Calif., he junked the time clocks. Salespeople were not forced to produce detailed expense reports but were trusted to spend their monthly expense allowances wisely.

Assembly line workers were paid as much as 25% more than minimum wage. After Kay noticed that the workers who put the final touches on a product at the end of the line seemed a lot happier than the ones at the start, he developed self-governing teams of six to nine employees who did it all.

“We regard management as basically an affair of teaching and training, not one of directing and controlling,” he told an interviewer. “We control the process, not the people.”

While the team idea is commonplace now, it was so innovative at the time that the renowned psychologist Abraham Maslow spent a summer in Kay’s plant, which he chronicled in his 1965 book, “Eupsychian Management.” “Eupsychian” was a Maslow coinage meaning human-centered.

The company, then called Non-Linear Systems, produced the digital voltmeters that Kay invented in 1953. They were said to be the first electronic test instruments to use a digital display instead of the less precise readings afforded by a needle on a dial.

In the 1970s, Non-Linear was battered by competition from large companies and cuts in the aerospace industry. Drawn to the burgeoning personal computer industry, Kay, with his son David, designed the all-in-one Kaypro, a compact unit meant to compete with the standard set-up of separate devices connected by a tangle of cables.

Among the Kaypro’s first users was a young Pizza Hut marketing executive who each night would sign on to an early Internet service from his apartment in Wichita, Kan.

“I remember it being frustrating,” Steve Case told Time magazine in 1997, “but there was something magical about the notion of sitting in Wichita and talking to people from all over the world.”

Case went on to found AOL.

Born in Akron, Ohio, on Jan. 22, 1919, John Francis Kopischiansky grew up in Clifton, N.J., the son of immigrants from a region in what is now Poland. He graduated from MIT in 1940 and worked for a defense company during World War II.

He moved to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1949, when he shortened his name to Kay. He and his family later moved to Del Mar, Calif., and he started Non-Linear in 1952.

After the company morphed into Kaypro, it underwent a tremendous growth surge, with revenues peaking at $125 million in 1983.

However, the growth also had chaotic aspects. Parts for Kaypro computers were stored in as many as 40 trailer trucks and a 20,000-square-foot white circus tent set up on the company’s eight-acre property.

While Kaypro outlasted some of its competitors, it failed after Kay refused to ship manufacturing overseas, said David Kay, who in 1988 left the company he had served as head of marketing.

“He was loyal to the people he worked with for 30 or 40 years,” David Kay said. “He wouldn’t move their jobs.”

Andrew Kay’s father, Fyodor Kopischiansky, worked for him as a maintenance supervisor until he was 98, when the Kaypro plant closed.

Kay continued in the computer business well into his 80s, supervising a few employees who built custom desktops for businesses in San Diego.

Mary Marble Kay, his wife of 66 years, died in 1996.

In addition to his son David, he is survived by his son Allan; daughters Janice and Nancy; 14 grandchildren, and 26 great grandchildren.

steve.chawkins@latimes.com

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.