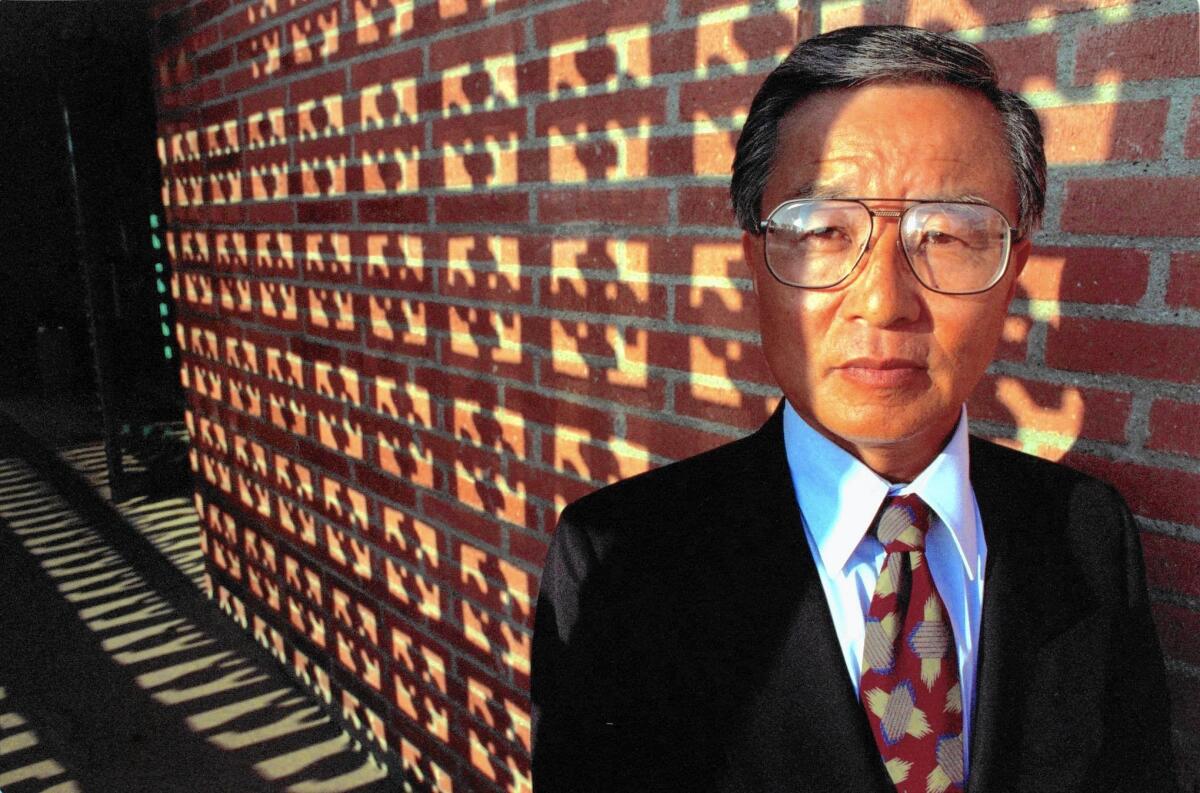

Donald Chung dies at 82; Korean War vet became author, doctor, donor

Fleeing his North Korean village in wartime 1950, Donald Chung promised his mother he would be back within three days.

He never saw her again. Unable to return, Chung went on to fight on the side of South Korea in the Korean War, endure bruising hardships and make his way to the U.S., where he became a highly respected cardiologist in Long Beach.

In the 1990s he gave more than $500,000 — the largest single donation — toward creating the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. But his life was haunted by the fact that his mother died before he was able to return to his native country, 33 years after his promise.

Chung, 82, died Nov. 3 at Long Beach Memorial Medical Center. He had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage about a week before, said his son Richard Chung.

Donald Chung’s 1989 memoir, “The Three Day Promise,” had a limited audience until his wife, Young Chung, suggested he send a copy to Abigail Van Buren, author of the nationwide “Dear Abby” advice column.

Van Buren was so taken with Chung’s saga that she made the book the sole subject of a “Dear Abby” column, calling it “one of the most fascinating, educational and inspirational books” she had ever read. Suddenly, Chung was a popular author, with thousands of letters pouring in. When he told Van Buren he was overwhelmed, she suggested he get an automatic letter opener.

“I had never heard of an automatic letter opener before. I am a heart surgeon,” he said in a 1995 Times interview.

Chung gave the proceeds of the book to the establishment of the memorial that opened in 1995.

He was born Dong Kyu on Feb. 6, 1932, in the small town of Chuul near the northeastern coast of what is now North Korea. His first exposure to Western-style medicine was in 1945, when his life was saved by a Japanese doctor who performed emergency surgery to treat his ruptured appendix.

“It made a deep and lasting impression,” he said in his book. “I realized that myth and mystery had no place in treating the ill.”

When the Korean War began in 1950, he was a beginning medical student and felt relatively safe while South Korean troops held the Chuul area. But when they began to retreat, he feared advancing North Korean forces would take him prisoner or kill him because he had ignored an induction notice.

Chung pinned his hopes on a report that it was to be a short, tactical retreat, but the column of retreating forces he joined traveled all the way to South Korea. Shortly after arriving, he and other refugees were inducted into the South Korean army. Chung was issued a flimsy uniform and vintage rifle, and shortly thereafter plunged into battle.

He and the other refugees-turned-soldiers were often under fire, hungry and cold during the war years. Of the 151 members of his army company, only about 40 were still alive when a truce ended the fighting in 1953.

Unable to return home, Chung attended Soo-Doo Medical College in Seoul, graduating in 1960. Two years later he came to the U.S. for a residency at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, where he also trained as a cardiologist. He was hired into a private practice in Long Beach in 1971.

In 1983, through a contact in Canada, he secured permission to visit North Korea. But before he departed came the news on “the saddest day of [his] life” that his mother had died several years before.

He dedicated his veterans memorial donation to her. “I want to honor my mother,” he told The Times, “to let her know that in my own way, I have kept my promise.”

In addition to his wife, Young, and son Richard, he is survived by another son, Alex, and four grandchildren. All live in Long Beach.

The family does not know whether his three sisters in North Korea are still alive.

david.colker@latimes.com

Twitter: @davidcolker

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.