George McGovern dies at 90; liberal standard-bearer against Nixon in ’72

- Share via

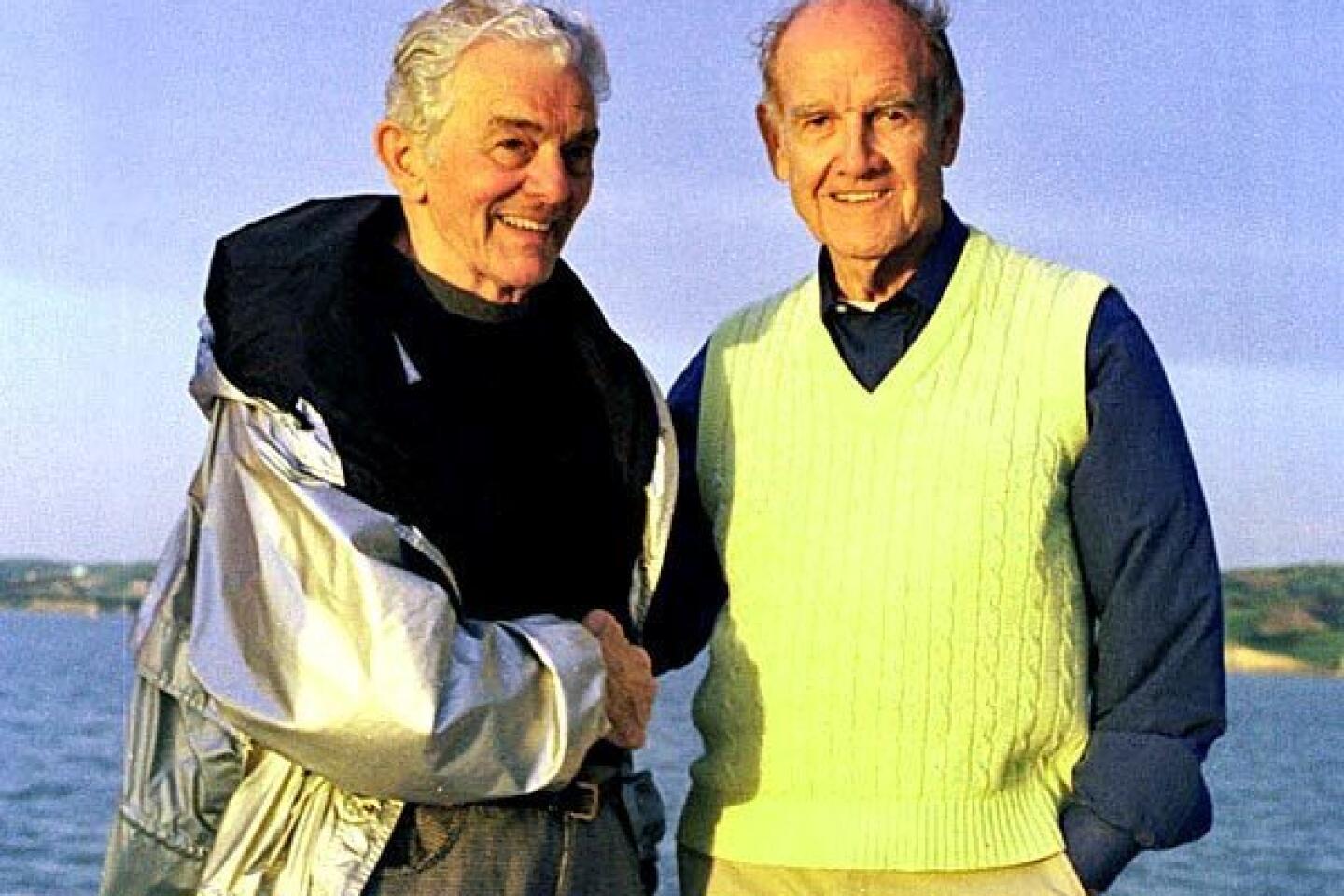

George S. McGovern, an icon of American liberalism who campaigned for the White House with moral fervor against President Richard M. Nixon and the Vietnam War but lost in a thundering landslide, has died. He was 90.

McGovern died Sunday morning while under hospice care in Sioux Falls, S.D., said family spokesman Steve Hildebrand. He had been hospitalized for various illnesses and injuries since suffering a serious fall last December.

A three-term U.S. senator from South Dakota, McGovern won the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. His hard-fought campaign against Nixon and the war in Southeast Asia attracted millions of angry, anti-Establishment voters, including women and minorities, long-haired students and buttoned-down idealists.

PHOTOS: George S. McGovern | 1922-2012

He chose Sen. Thomas Eagleton of Missouri to be his vice presidential running mate without knowing that Eagleton had a history of depression. When the revelation caused criticism, McGovern dumped him, only to end up looking fickle. He also fell victim to some of the transgressions of Watergate, the scandal that ultimately forced Nixon to resign. But public outrage came too late, and McGovern suffered one of the biggest defeats in U.S. history.

His campaign left a significant legacy, including his proposals, since fulfilled, that women be appointed to the Supreme Court and nominated for the vice presidency. He inspired scores of budding politicians: Bill Clinton was his Texas coordinator before becoming governor of Arkansas, then president. Gary Hart was his campaign manager before becoming a senator from Colorado, then a candidate for the White House.

FOR THE RECORD:

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the number of George McGovern’s surviving grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

McGovern was a die-hard idealist. His electoral loss embittered him, but not for long. He never abandoned his optimism or his faith in humanity. Neither did he give up his devotion to liberalism or what colleagues called his extraordinary sense of decency.

George McGovern was born July 19, 1922, in a parsonage in Avon, S.D., and grew up in Mitchell. His father was a fundamentalist Methodist minister and a political conservative.

McGovern enrolled at Dakota Wesleyan University and married classmate Eleanor Stegeberg on Oct. 21, 1943. But within months, he left to fly a B-24 in World War II. On his bunk, he read philosophy and history. The books broadened him, and he came home, he said, wanting to know more about “the nature and destiny of man, about the adequacy of our contemporary value system and the capacity of our institutions to nurture those values.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2012

He also returned a hero. On one of 35 missions against Nazi targets in Europe, he took hits that blew out most of the nose of the plane and wounded a gunner. Shrapnel cut the hydraulic brake and electrical lines. He ordered his crew to crank down the landing gear and tie parachutes to girders just inside the rear hatches. He landed and released the parachutes. Not a life was lost. McGovern was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war he returned to Dakota Wesleyan, then entered Garrett Theological Seminary in Chicago. He liked preaching, but the counseling and ceremonies that were part of ministry held little appeal. So he switched to Northwestern University and history.

He read Hegel, then Walter Rauschenbusch, a noted advocate of what was called the social gospel. To McGovern, it meant applying the idealism of Christianity, and it became his secular belief. He supported the Progressive Party’s Henry Wallace for president in 1948. But, according to Robert Sam Anson’s “McGovern: A Biography” (1972), McGovern grew disillusioned by fanaticism among Wallace’s supporters, so he became a Democrat. He opposed the Korean War and favored recognition of the communist government of Beijing. He earned a doctorate in history and returned to Dakota Wesleyan to teach.

“The principal reason I wanted to move from the classroom into politics [was] that I felt I could influence the course of history more directly,” Anson quotes McGovern as saying.

In 1956 he ran for Congress and became the first Democrat from South Dakota to be elected to the House of Representatives in 22 years. After two terms, he ran for the Senate in 1960, but lost.

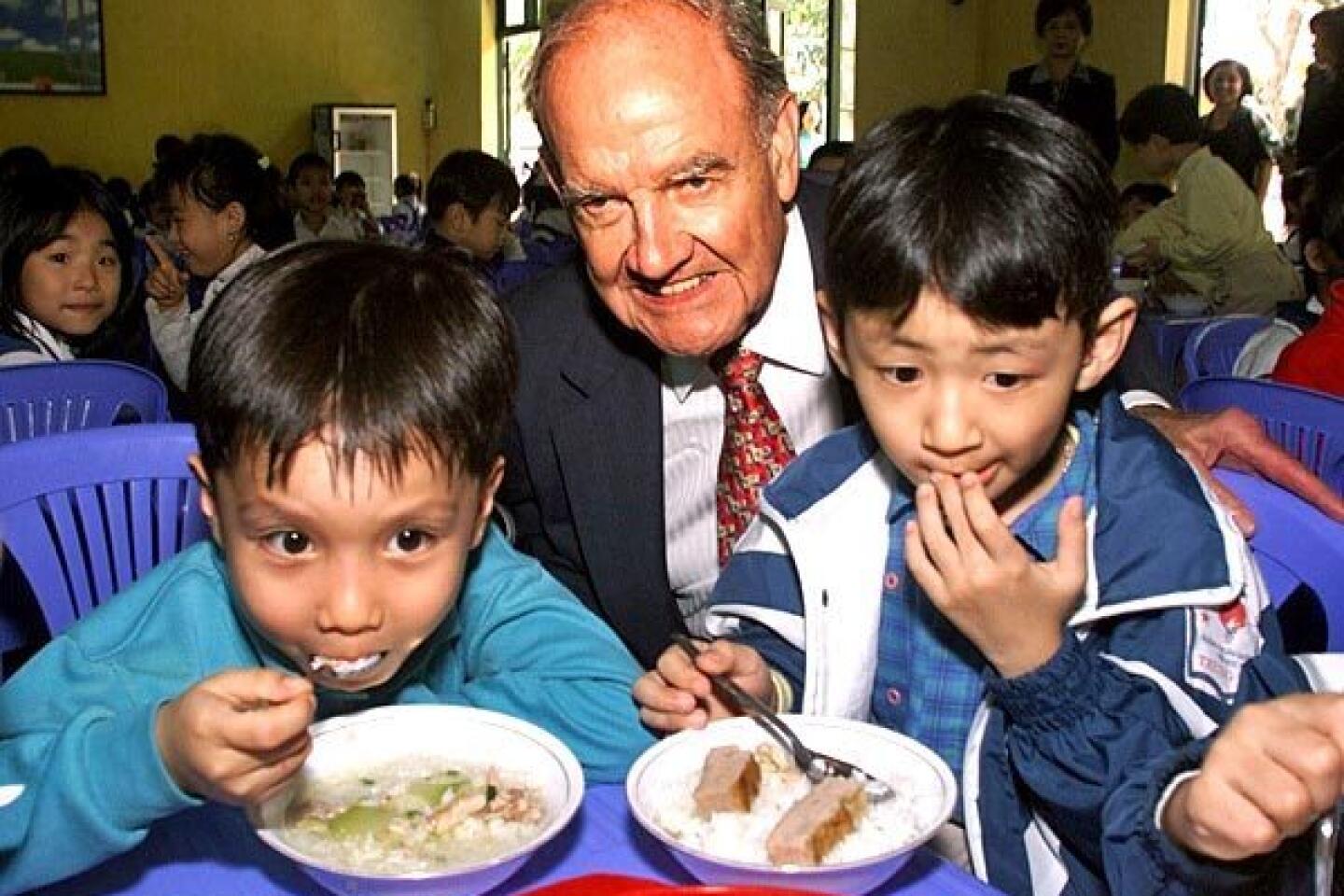

Newly elected President John F. Kennedy asked McGovern to open an agency to send surplus food abroad. By late 1961, McGovern had Kennedy’s Food for Peace program operating in a dozen countries. It was one of McGovern’s proudest achievements.

In 1962, he became the first Democrat elected to the Senate from South Dakota in 26 years. His chief interest was world peace. He challenged “our Castro fixation,” decried America’s capacity for nuclear “overkill” and proposed a $4-billion reduction in the U.S. defense budget. He also supported Medicare, school lunches and the war on poverty.

Conservative South Dakotans reelected him twice, despite his 81% rating from the liberal Americans for Democratic Action. Part of his success was his attention to constituents. But another part was his authenticity, decency and sense of mission. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-N.Y.) noticed it. “Of all my colleagues,” he said, “the person who has the most feeling and does things in the most genuine way is George McGovern.”

McGovern was one of the first senators to warn against involvement in Vietnam, in 1963. Two years later, he opposed extending the fighting into North Vietnam and called the war a “moral debacle.” After Robert Kennedy was assassinated during his run for president, McGovern mounted his first campaign for the White House. He was defeated at the 1968 Democratic Convention, where young antiwar protesters were clubbed by police on the streets of Chicago.

Four years later, with antiwar sentiment at a pitch, he ran for president again. Almost immediately, McGovern became a target of attacks that grew into Watergate. President Nixon’s aides saved their worst for other Democrats, because Nixon thought McGovern would be easier to beat. Nonetheless, they took steps to insert a Nixon “plant” into McGovern’s campaign.

In his authoritative 1976 book, “Nightmare: The Underside of the Nixon Years,” J. Anthony Lukas documented how Nixon’s aides did better than a single “plant.” They placed a spy among reporters covering McGovern’s campaign, they sent a private investigator to infiltrate his state campaign in California, and they inserted still another spy into his national headquarters near Capitol Hill.

This spy provided a floor plan, including electrical outlets and air ducts. Nixon’s men used it in several attempts to install electronic listening devices inside McGovern headquarters. Only after failing at this did they break into and bug the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex.

But that was not all. A private eye spied on McGovern headquarters at the Democratic convention in Miami, and a Nixon operative hired an airplane that flew over the convention with a sign: “Peace, Pot, Promiscuity. Vote McGovern.”

Supported by party irregulars, McGovern won the Democratic presidential nomination at a chaotic convention. He picked Eagleton as his vice presidential candidate, only to learn that his running mate had suffered depression and taken electric shock therapy. The public fretted that a potential commander in chief might become dangerously depressed. McGovern said he stood behind Eagleton “1,000%” and would keep him on the ticket.

In the end, however, McGovern could not weather the political storm, and he dumped Eagleton. Then he was seen as disloyal and indecisive.

On Election Day, he won only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. He stands tied with Walter F. Mondale, who lost to Ronald Reagan, for the worst state-by-state thumping in U.S. history.

In time, Nixon and his vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, were forced to resign, and more than 30 administration officials, campaign officers and financial contributors pleaded or were found guilty of breaking the law or covering up illegal activity. Nixon might have gone to prison but for a pardon from President Ford, who had succeeded Agnew as vice president and then took over the presidency when Nixon quit.

Nonetheless, McGovern was marked as a loser. Bitter, he blamed reporters, voters and Eagleton. But by mid-1973, he was able to fault himself.

In 1974, McGovern won reelection to the Senate.

Six years later, his opponents called him a baby killer because he was pro-choice and was considered a traitor for voting to let Panama take control of the Panama Canal. The attacks, plus Reagan’s first fitting in presidential coattails, were too much, and they cost McGovern his Senate seat.

In 1984, he ran again for president, preaching a resolutely liberal message. Instead of soldiers, he said, send envoys into hot spots. Be more even-handed in the Middle East. Use defense savings to build a new railroad system, create jobs, save fuel and cut pollution. Offer cheap loans to first-time home buyers. Give surplus food to the hungry.

He could not resist a dig at Watergate. “At least,” he told his campaign audiences, “I don’t have to check in with a probation officer before coming here.”

Even so, McGovern visited Nixon and made peace.

When he failed to place second in the Massachusetts primary, the only state that had voted for him 12 years before, he withdrew. But he had won back his dignity. For many, he became an icon of liberalism.

McGovern returned to teaching and for several years headed the Middle East Policy Council, dedicated to informing Americans about Islam and the Arab world.

But his later years were torn by personal tragedy. His daughter Teresa, who suffered from depression and alcoholism, was found in December 1994 in Madison, Wis., frozen to death in the snow after an evening of drinking. She was 45 and the mother of two.

In her diary, McGovern read how she had suffered as a youngster through his long campaigns and his endless nights in the Senate and how she had missed him and felt desolate, rejected and abandoned.

McGovern was overwhelmed with guilt. “I’d give everything I have, and I mean everything,” he told The Times, “for one more afternoon with [her], just to tell her how much I loved her.”

In deep depression himself, he sought help and finally regained his health.

Then, in 1998, his son, Steven, also an alcoholic, was jailed in Massachusetts after pleading guilty to beating his female companion.

Yet McGovern’s optimism was undiminished. Teresa’s death, he said, simply renewed his compassion for others. “I guess I’ve always been an optimist,” he once told a reporter. “I don’t know how you can live any other way.”

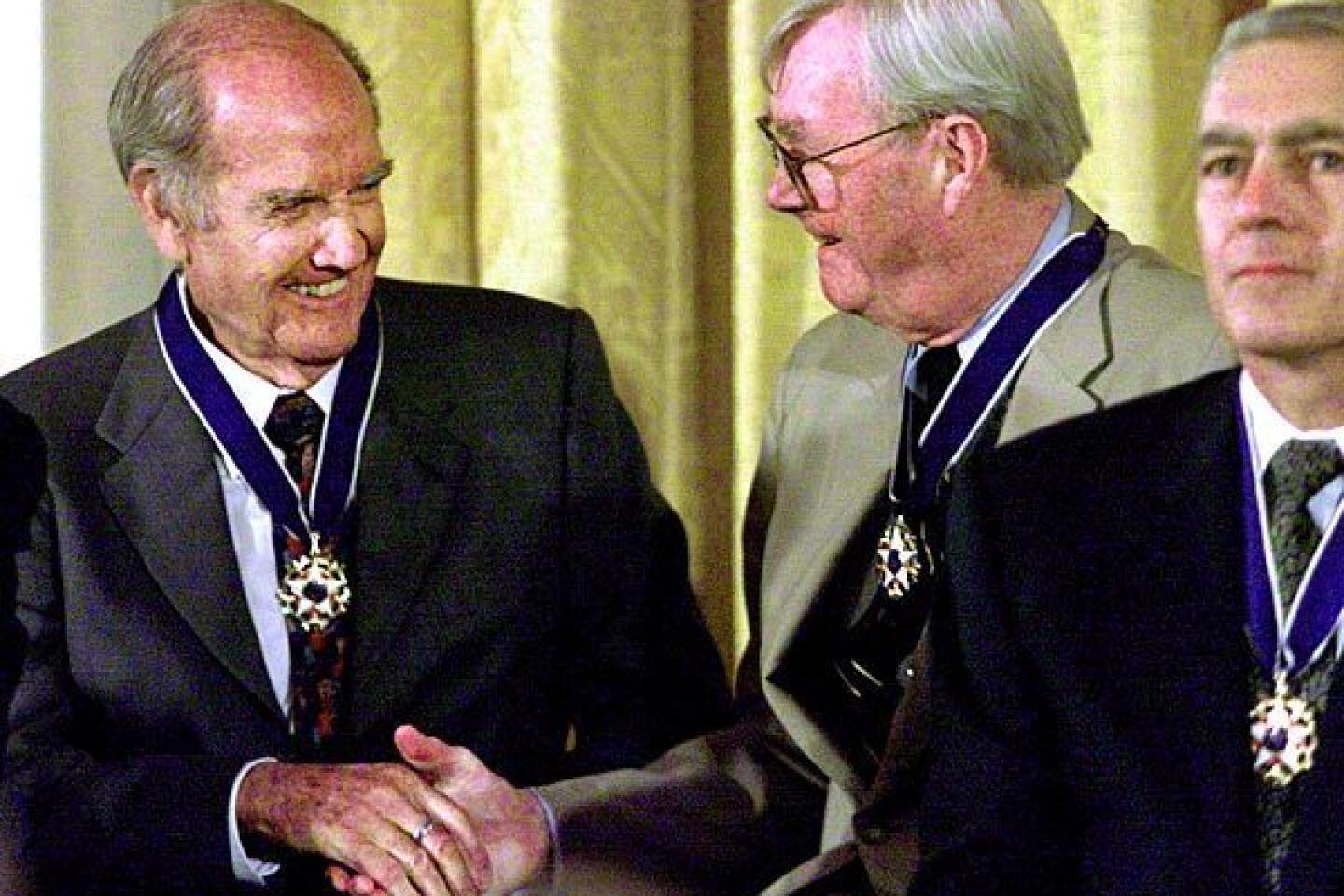

In 1998, Clinton sent him to Rome as the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. In 2000, Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. A year later, the U.N. made him its first global ambassador to ease hunger. In 2008, McGovern and his former Senate colleague Bob Dole (R-Kan.) shared the World Food Prize, sometimes called the Nobel Prize for combating hunger.

Over the years, McGovern published a dozen books. His last, “What It Means to Be a Democrat” (2011), summed up his political beliefs.

Be compassionate, he urged. Put government to work to help the less fortunate. End hunger. Spend more for education. Protect the environment. Reduce military spending. And forge peace in the Middle East by listening to all parties.

McGovern’s wife, Eleanor, died in 2007 and his son, Steven, this past July. He is survived by his daughters Ann, Susan and Mary, 10 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Meyer is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.