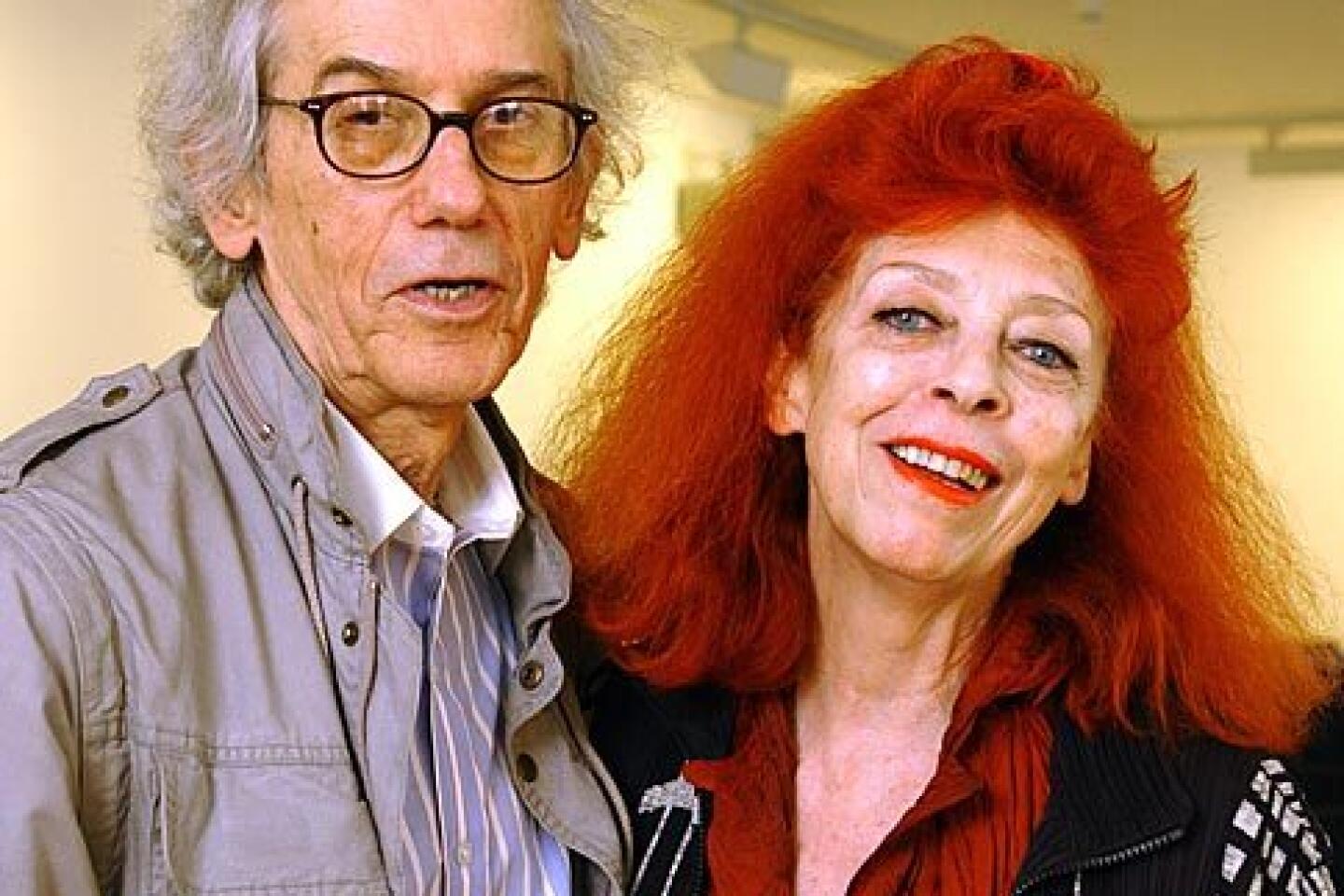

Jeanne-Claude dies at 74; collaborated with artist-husband Christo

- Share via

Jeanne-Claude, whose collaboration with her husband Christo in creating massive environmental works of art such as the 24-mile-long “Running Fence” in California in the 1970s attracted worldwide attention for decades, has died. She was 74.

Jeanne-Claude, who, like her more famous husband, used only her first name, died Wednesday night in a New York hospital from complications of a brain aneurysm, her family said in a statement.

The husband-and-wife team had been involved in creating large-scale, temporary environmental art projects since 1961, including wrapping the Reichstag in Berlin in more than a million square feet of silvery polypropylene fabric in 1995.

In 1976, they installed “Running Fence,” which consisted of 2,050 white fabric panels extending across 24 1/2 miles in Sonoma and Marin counties.

Returning to California in 1991, they installed 1,760 gigantic, custom-made yellow umbrellas along an 18-mile stretch of the Tejon Pass, about 60 miles north of Los Angeles. A bi-continental project known as “The Umbrellas,” it included the installation of 1,340 blue umbrellas in Ibaraki, Japan.

“The Umbrellas” had a tragic twist when high winds tore one of the 485-pound umbrellas from its stand and killed Lori Keevil-Mathews, a Camarillo insurance agent who was viewing the art project with her husband, Michael Mathews.

In 2005 came “The Gates,” in which more than 7,503, 16-foot-tall vinyl gates with free-flowing saffron-colored fabric panels were set up along 23 miles of walkways in New York City’s Central Park. The self-financed project cost $21 million.

As is typical of their work, “The Gates” was dismantled after 16 days.

“We create for us,” the flame-haired Jeanne-Claude insisted in a 2005 interview with the Washington Post. “We don’t create for the public. But, of course, those who like it, that’s a bonus for us.”

In an interview with New York’s Newsday the same year, she explained the temporary nature of their work with an anecdote.

“One of our workers on the night shift asked me why is it temporary,” she said. “I told him to think of a rainbow. And he grabbed my arm and says, ‘I think I got it: If the gates were there all the time, after a while nobody would be looking at them and the magic would be gone.’ And I said, ‘You’ve got it better than most art historians.’ ”

The Manhattan couple maintained their artistic freedom by never accepting sponsorships. Instead, they reportedly financed all their projects through the sale of Christo’s artwork, including preliminary drawings and collages of their projects.

For years, Jeanne-Claude was known for being her artist husband’s hard-nosed business manager. But they reportedly collaborated in envisioning their attention-getting outdoor projects and began putting both their names on their work in the ‘90s.

“It’s two artists,” Jeanne-Claude said in a 1995 Washington Post interview. “There is no longer the artist Christo. That doesn’t exist anymore. We have officially changed our name, repairing a 37-year-old mistake. We feel we are old enough now to tell the truth. Now it is Christo and Jeanne-Claude.”

In the same interview, Christo credited his wife with some of their most successful projects, including “Surrounded Islands,” in which pink woven polypropylene fabric floated around 11 islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay in 1983.

Asked why they had decided to now share the spotlight, Jeanne-Claude said that when they began collaborating on their projects “it was already hard enough trying to explain that it was a work of art. . . . Trying to explain that it was a work of art done by two artists was twice as difficult.

“Therefore, we were perfectly satisfied when we decided in 1961, when we did our first work of art, that there would be the artist and the manager.”

But as she frequently made clear in interviews, she was not an artist when they first met.

“I became an artist out of love for Christo,” she said. “If he had been a dentist, then I would have become one too.”

The daughter of a prominent French army officer, Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon was born June 13, 1935, in Casablanca, Morocco. By coincidence, Christo Javacheff was born the same day in Bulgaria.

Educated in France and Switzerland, she earned a bachelor’s degree in Latin and philosophy from the University of Tunis in 1952.

She met Christo in Paris in 1958 when he was commissioned to paint a portrait of Jeanne-Claude’s mother. Their son, Cyril, a poet, was born in 1960.

Their website said Christo is “dedicated” to completing their works-in-progress: “Over the River” a project over sections of the Arkansas River in Colorado; and “The Mastaba,” a project for the United Arab Emirates.

A date for a memorial service will be announced later.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.