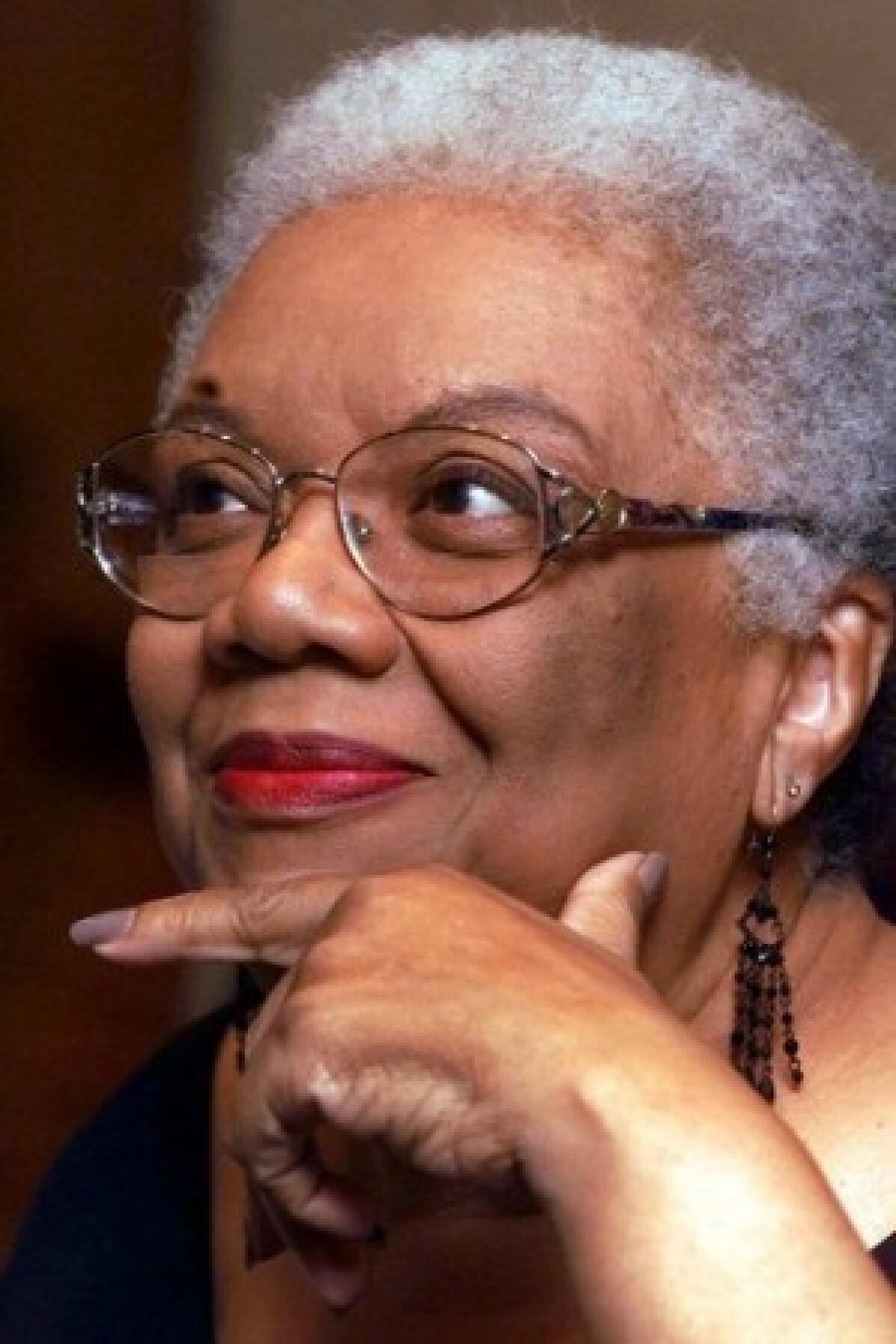

Lucille Clifton dies at 73; award-winning poet

- Share via

When Lucille Clifton was a girl in the 1940s, she saw her mother burning poems in their furnace. A grade-school dropout who loved words and wrote traditional verse, her mother had an offer to publish her work in a book, but her husband and children scorned the idea of a poet in the family.

Their rejection was so stinging that she turned the cherished words to cinders in a fit of fury and sorrow that Clifton never forgot:

her hand is crying.

her hand is clutching

a sheaf of papers.

poems.

she gives them up.

they burn

jewels into jewels.

her eyes are animals.

each hank of her hair

is a serpent’s obedient

wife.

she will never recover.

Clifton’s drive to write, her “wish to persist,” may have been born in that moment of witness. During a four-decade career, she produced 12 volumes of poems, three of which were nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and one of which -- “Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems, 1988-2000” -- won the National Book Award in 2000.

In 2007, she became the first African American woman to win the $100,000 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. Last month, the former poet laureate of Maryland and descendant of slaves added the Frost Medal of the Poetry Society of America to a long list of honors.

Known for elegant, spare poems that distilled the voices of African Americans and others, Clifton died Feb. 13 in Baltimore of a bacterial infection, according to St. Mary’s College of Maryland, where she taught for 18 years until her retirement in 2007. She was 73.

Her death caught fellow poets by surprise. She was a poet who celebrated survival, a theme inspired by historic tragedies as well as personal ones, including molestation as a child, kidney failure, cancer and the deaths of her husband and two of their children.

These adversities informed her highly autobiographical poems, which flowed with what poet Elizabeth Alexander, writing on the New Yorker’s website last week, called “a quiet, even woman’s voice telling sometimes terrible truths.” Or, as Clifton herself once said, “I am a black woman poet, and I sound like one.”

She had a parallel career as a prolific children’s author, whose 21 books -- often featuring a black boy named Everett Anderson -- offered messages about self-acceptance and tolerance for others. But she considered herself first and foremost a poet.

Born Thelma Lucille Sayles on June 27, 1936, in Depew, N.Y., she traced her roots to West Africa, where her great-great-grandmother was trapped by the slave trade.

Neither her father, a steelworker, nor her mother, a laundress, had much formal schooling, but they were voracious readers who lit a flame for learning in their daughter.

Clifton entered Howard University in Washington, D.C., at 16 to study drama and appeared in the first performance of James Baldwin’s “The Amen Corner.” But she neglected her studies and had to leave when she lost her scholarship. She transferred to what is now the State University of New York at Fredonia, where she joined a group of black intellectuals that included the writer Ishmael Reed and her future husband, Fred Clifton, whom she married in 1958.

Her career took off in 1969 with her first volume of poems, “Good Times,” chosen by the New York Times as one of the year’s 10 best books. Langston Hughes included some of her work in his 1970 anthology, “The Poetry of the Negro.”

These achievements were remarkable in light of the fact that Clifton by then had six children under the age of 10. She often joked that the crush of motherhood was the reason her poems were usually no longer than 20 lines. She composed them in her head, dispensed with capitalization and most punctuation, and favored a form so lean that, as critic Peggy Rosenthal once noted, “its spaces take on substance.”

Some of her poems were directed at the indignities of poverty. Others ruminated on injustice, as in “jasper texas 1998,” written in the voice of a black man named James Byrd Jr. who was chained to a pickup by three white men and dragged on a rocky road until he was decapitated:

i am a man’s head hunched in the road.

i was chosen to speak by the members

of my body.

Many of her poems offered earthy humor on taboo subjects such as menstruation. Her imposing physique suggested what Dana Gioia, the poet and former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, called “her most famous poem by a humongous margin,” the rollicking “homage to my hips”:

these hips have never been enslaved,

they go where they want to go

they do what they want to do.

these hips are mighty hips.

Clifton suffered many losses in later years. She had several occurrences of cancer and spent a year in dialysis before a kidney transplant.

Her husband, who taught philosophy at the University at Buffalo, died in 1984. A son, Channing, and a daughter, Frederica, also died. She is survived by three daughters, Sidney, Gillian and Alexia; a son, Graham; and three grandchildren.

Through the hardships, she wrote poems that urged gritty optimism, even transcendence, as in “blessing the boats”:

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.