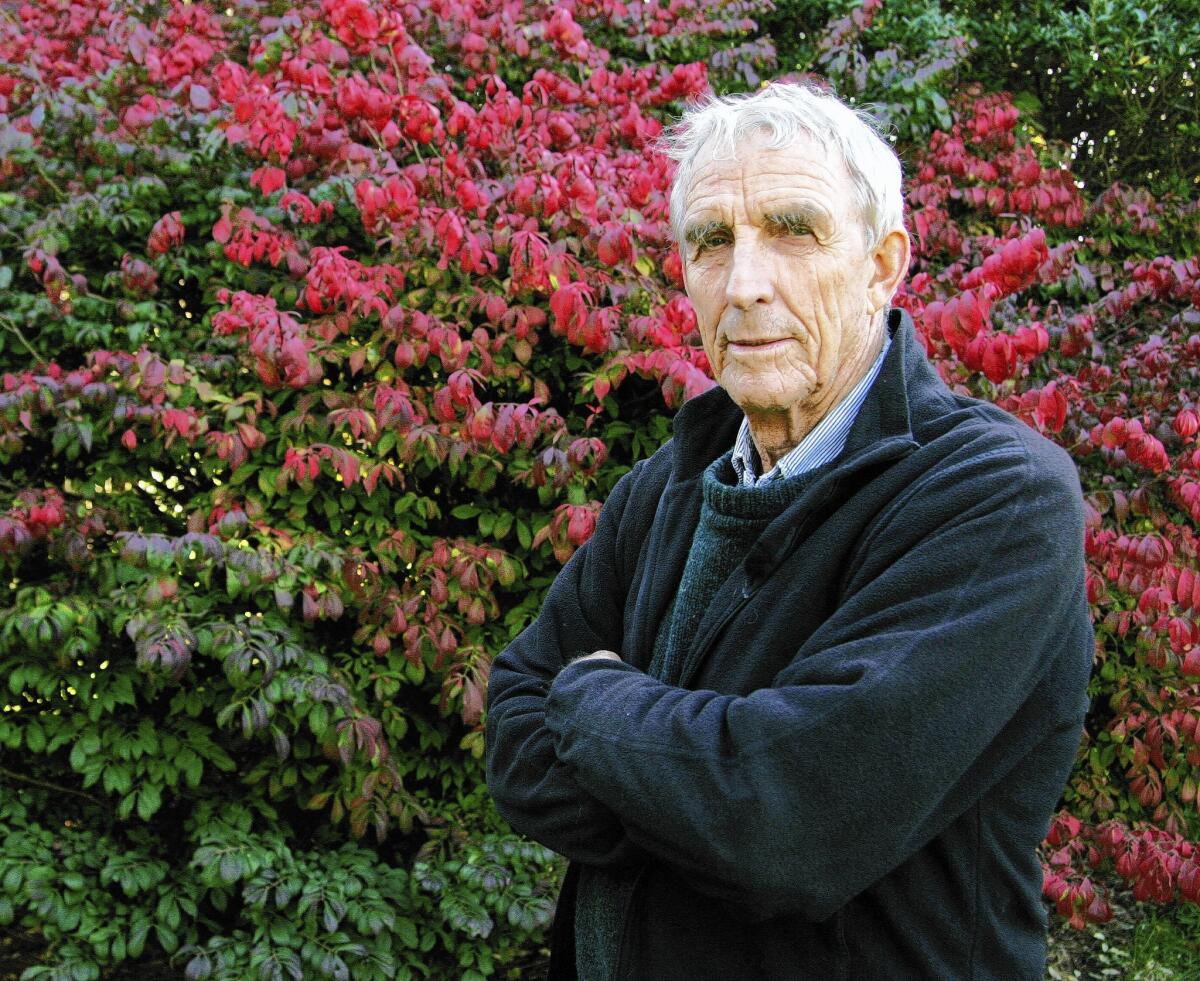

Peter Matthiessen dies at 86; novelist and naturalist

- Share via

In interviews, Peter Matthiessen always had to answer, in his correct, patrician tones, a question seldom put to other writers: Just what kind of writer, exactly, are you?

The confusion was understandable. Matthiessen, the only writer to win the National Book Award in both fiction and nonfiction, was both an elegant novelist and a rugged naturalist, a traveler known for his graceful yet spare descriptions of the wildest places on Earth.

FOR THE RECORD:

Peter Matthiessen: In the April 7 LATExtra section, the obituary of Peter Matthiessen, author of “The Snow Leopard,” said that he died at a hospital near his home in Sagaponack, N.Y. He died at home.

Over six decades, he produced acclaimed volumes of natural history based on his treks through East Africa, New Guinea and the Amazon. He chronicled the plight of disappearing tribes. He wrote books about Cesar Chavez and Native American activist Leonard Peltier. He became a Zen devotee and wrote of a painful spiritual journey as he hiked through the Himalayas in “The Snow Leopard.” At the same time, he wrote fiction; four of his novels centered on a respected and reviled sugar-cane planter who was killed by his neighbors in the Everglades.

He also helped found the Paris Review, the renowned literary magazine, which he used as a cover during his brief career as a spy for the CIA.

Matthiessen died Saturday at a hospital near his Sagaponack, N.Y., home, his publisher, Riverhead Books, announced. He had been undergoing leukemia treatment for more than a year. He was 86.

His final work, “In Paradise,” a novel inspired by a Zen gathering he attended at Auschwitz, is due out Tuesday.

The late novelist William Styron once said that Matthiessen produced “as distinguished a body of work as any writer of our time.”

“He has immeasurably enlarged our consciousness,” Styron said.

In a 1975 Los Angeles Times review of the novel “Far Tortuga,” Peter Benchley, the author of “Jaws,” wrote that Matthiessen “need tip his hat to no man, not to Melville or Conrad, when it comes to writing about the sea.”

“He knows it and loves it,” Benchley wrote, “and one is tempted to suppose that the sea bestowed upon him the words with which it would like to describe itself.”

With dialogue in the Cayman dialect, “Far Tortuga” is based on a voyage Matthiessen made aboard a turtle-hunting boat off the coast of Nicaragua. The descriptions are lean — influenced, Matthiessen told the Paris Review in 1999, by his Zen training.

“The grit and feel of this present moment, moment after moment, opening out into the oceanic wonder of the sea and the sky. When you fix each moment in all its astonishing detail, see its miracle in a fresh light, no similes, no images are needed,” Matthiessen said. “They become ‘literary,’ superfluous. Aesthetic clutter.”

Among Matthiessen’s best-known books is “At Play in the Fields of the Lord,” a 1965 novel about missionaries, mercenaries and an elusive tribe in the South American rain forest. It was turned into a 1991 film starring Tom Berenger, John Lithgow and Daryl Hannah.

Born in New York City on May 22, 1927, Matthiessen was the son of an architect and grew up in privilege. After boarding school in Connecticut, he served in the U.S. Navy and then attended Yale, spending a year at the Sorbonne in Paris.

During college, he later said, a professor recruited him for the CIA.

“I was just a greenhorn,” he told an interviewer at Penn State in 2009. “I didn’t have any politics at all. I was just a Yalie.”

After a couple of years in Paris, where he was writing his first novel, “Race Rock,” and working on the Paris Review with his friend George Plimpton, he left the agency. The communists he tracked were “humorless and wrong-headed,” he said, “but they were honest and committed.”

Moving to the eastern tip of Long Island, where his family had summered, he worked as a commercial fisherman as he continued to write. The experiences later surfaced in a 1986 nonfiction book, “Men’s Lives: The Surfmen and Baymen of the South Fork.”

In 1956, Matthiessen started traveling seriously. Loading a shotgun, a sleeping bag and a few texts into his Ford convertible, he visited wildlife refuges across the U.S. The result was an encyclopedic work called “Wildlife in America.”

In years to come, Matthiessen traveled to remote corners of Alaska, Siberia, Peru, East Africa, Nepal and elsewhere. In central New Guinea, he was part of the 1961 Harvard-Peabody expedition that chronicled a Stone Age tribe, the Kurelu. Michael Rockefeller, the son of then-New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, disappeared on the same expedition.

Matthiessen’s most controversial work was “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse,” a critical look at the conviction of Leonard Peltier in the 1975 murders of two FBI agents. Lawsuits filed by an FBI agent and South Dakota’s former governor, Bill Janklow, were dismissed in 1990.

His most ambitious fiction was the National Book Award-winning “Shadow Country,” a massive novel based loosely on the life of Edgar Watson, a charismatic but murderous landowner in the Everglades. Matthiessen had heard as a teenager that Watson, who owned the only house in the huge swamp, died after neighbors shot him 33 times.

Intrigued by the story, Matthiessen wrote three novels telling the tale from different points of view: “Killing Mr. Watson,” “Lost Man’s River” and “Bone by Bone.” “Shadow Country” was a reworking of those books.

As to just what kind of a writer he was, Matthiessen was clear: He was a fiction writer who also wrote nonfiction, not the other way around.

At the end of a day writing nonfiction, he said, he felt drained from arranging “my set of facts.”

But “deep in a novel, one scarcely knows what may surface next.... In abandoning oneself to the free creation of something never beheld on Earth, one feels almost delirious with a strange joy.”

Matthiessen, who was married twice before, is survived by his wife, Maria, two daughters, two sons, two stepdaughters and six grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.