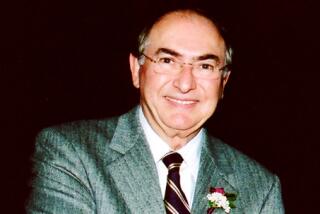

Robert Berke dies at 61; activist lawyer

- Share via

Robert Berke, an activist lawyer known for battling government injustice, particularly in defense of poor clients and victims of police misconduct, died Saturday at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica after a sudden illness. He was 61.

The cause was meningoencephalitis, an inflammation and infection of the brain and its lining, complicated by pneumonia, said attorney Gigi Gordon, a longtime friend and colleague.

Berke practiced law in Los Angeles for 36 years, first as a public defender and later at the Center for Law in the Public Interest and at private firms.

“He was one of the most respected defense lawyers in this community,” said Mark Rosenbaum, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “He made it his life’s mission to ensure that the state not be permitted to deny the dignity of individuals, whether they were complaining of police misconduct or whether they were incarcerated.”

As a public defender from 1973 to 1981, Berke played a leading role in two landmark cases that expanded access to police personnel files in cases alleging a pattern of officer misconduct. Kelvin L. vs. Superior Court (1976) pertained to prior acts of excessive police force, while People vs. Zamora (1980) established that the destruction of evidence deprived the defendant of a fair trial.

“This was the first successful effort by lawyers to pierce the shield of police officer confidentiality,” said Gordon, who directs the Post-Conviction Assistance Center, a public interest law firm funded by L.A. County. “It changed the legal landscape in a lot of ways.”

Berke also helped defend a number of inmates wrongfully convicted because of false testimony by jailhouse informants. In 1991, his client Arthur Grajeda was freed from life imprisonment after Berke proved that the informant in his case was not credible. It was the first reversal to result from a scandal that The Times exposed in the late 1980s when jailhouse informants were found to have received special favors in return for falsely reporting that other inmates had confessed to specific crimes.

In one of his longest-running legal battles, Berke and two colleagues, Janet Harold and Michael Rubin, established that lawyers who prevail in lawsuits brought in the public interest are entitled to compensation for their work. He and Rubin successfully argued the case before the California Supreme Court in 2008.

That fight stemmed from Harold and Berke’s advocacy on behalf of inmates in the state’s prisons who were being underpaid by outside employers, a violation of the Prison Inmate Labor Initiative of 1990. They won that case, Vasquez vs. State of California, but the state refused to pay the attorneys’ fees, although the so-called private attorney general statute requires the losing party to do so. The Supreme Court ordered the state to pay $1.25 million in fees for their nine-year effort.

Rubin said the high court ruling was a victory not merely for Harold and Berke but for all public interest lawyers in the state because it ensures that private lawyers “will take up the cudgel and work in the public interest and ensure that laws are enforced as the Legislature meant them to be enforced.”

Berke was born in New York City on March 18, 1948. He earned a bachelor’s degree at Pomona College in 1969 and a law degree at UCLA in 1973.

After eight years as an L.A. County public defender, he was a staff attorney for two years at the Center for Law in the Public Interest in West Los Angeles. From 1983 to 1990, he practiced at the firm of Overland & Berke in Santa Monica. Since 1991 he had a solo practice, also in Santa Monica.

He is survived by his mother, Sylvia Berke; and a son, Chad. Services will be at 1 p.m. Sunday at Kehillat Israel, 16019 Sunset Blvd., Pacific Palisades.

Berke waged one of his most impassioned crusades on behalf of a severely disabled 11-year-old orphan, Jesus Castro, whose parents committed suicide and who was nearly drowned by his step-grandmother. The boy was left blind and quadriplegic with the mental capacity of a 6-month-old. Berke sued the L.A. County Department of Children’s Services for failing to make routine visits to ensure the child’s safety while he was in his relative’s care and won a $5.4-million award. It was overturned on appeal but a confidential settlement with the county provided for the boy’s care.

The lawyer later forced the county to move Jesus from a state institution into a more home-like care facility. The day Jesus left the institution was, Berke told The Times, “the happiest day of my life.” He then found a new foster parent and the funding to build a home specially equipped for the boy and other children with severe medical disabilities. Jesus died a few months before he was to move in. Berke arranged his funeral and delivered a tearful eulogy.

“Bob was a true believer,” Gordon said. “He would fight endlessly and relentlessly because he decided the cause was just. He was a real cause guy. It defined his entire career.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.