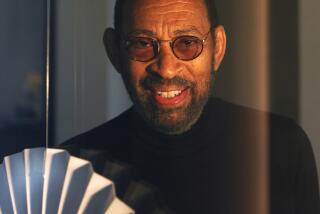

Robert Haines, who rose from deckhand to piloting Scripps’ research vessels, dies at 92

- Share via

Robert Haines, who spent most of his 92 years at sea aboard warships, research vessels, 8-foot dinghies and everything in between, died Jan. 26, ashore.

This sailor’s last wish, jotted on a sticky note, will correct that oversight. Haines asked that his ashes’ final resting place be in the Pacific, at a specified longitude and latitude midway between Coronado and the Coronado islands.

“Where an ocean eddy would keep his ashes forever swirling in the waters he loved to sail,” wrote Joe Ditler, a friend, “and the family he loved so deeply.”

During his 35 years with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Haines rose from deckhand to captain. While roaming the Pacific Ocean, he encountered an underwater volcano, witnessed an atomic bomb blast and charted a course through the eye of a tropical cyclone.

“The sun comes out and, while you still have big seas, there’s no wind,” he told Ditler. “As soon as the eye passes over you, you get hit again, and sometimes with winds close to 100 knots, and 50-foot waves.”

Robert Bentley Haines was born on Aug. 31, 1926, in Vallejo, Calif. His father was a submarine officer and moved his family frequently. “Baines,” as Haines was called, was introduced to Coronado as a boy and he learned to sail on Glorietta Bay.

During World War II, he dropped out of school to enlist in the Navy. Aboard the battleship Iowa, he fought in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and in Tokyo Bay witnessed Japan’s surrender.

In 1950, he took a job at Scripps as a deckhand. Except for a yearlong interruption, he would work there in various seagoing capacities until 1985. While aboard the research vessel Spencer F. Baird in 1952, he witnessed the detonation of the hydrogen bomb above Eniwetok, a Pacific island.

He rose quickly to the rank of captain, mastering the moods of the sea — and his crew members. Stephen Miller, who sailed with Haines on several Scripps expeditions, remembered the skipper handling a prickly scientist who never started work before 4 p.m.

Haines reset all the ship’s clocks so that the scientist would start his work earlier

Whether outmaneuvering a curmudgeon or shepherding a ship through a typhoon, Haines was unflappable. He could also be a genial host, once welcoming aboard CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, who had been reporting on deep sea submersibles.

On a passage through the Panama Canal, the skipper used his spare time to build an 8-foot Sabot-class sailboat. Back in San Diego, he gave it to his son, Robbie. The present helped launch a great sailing career — in the 1984 Olympics, Robbie Haines and two others would sail a Soling-class vessel to a gold medal.

“He was just a wonderful man,” said Amy Haines, his daughter-in-law. “He was very humble — he didn’t think any of what he had done was important or interesting. We did.”

Retiring from Scripps in 1985, Haines devoted himself to sailing — he was a Coronado Yacht Club member — golfing and family.

He is survived by his wife, Barbara; children Robbie, Pam Hardenburgh, Caroline and Bunnie Hamilton; four grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

Rowe writes for the San Diego Union Tribune

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.