Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter dies at 76; boxer wrongly imprisoned 19 years

- Share via

When Rubin “Hurricane” Carter was at his best as a boxer, it would have been impossible to foresee Nelson Mandela or Bob Dylan doing him any favors.

With his fearsome, drop-dead glare, precisely cut goatee and glistening, shaved head, Carter was violent and swaggering, a white racist’s caricature of a dangerous black man.

Talking to sportswriter Milton Gross for a 1964 story in the Saturday Evening Post, Carter made a widely publicized joking remark about killing cops in Harlem. At a weigh-in before a December 1963 fight against Emile Griffith, he chided his opponent by declaring: “You talk like a champ but you fight like a woman who deep down wants to be raped!”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2014

The fight was stopped two minutes and 13 seconds into the first round, with Griffith collapsing in pain as Carter pummeled him, yelling: “You gotta pay the Hurricane!’”

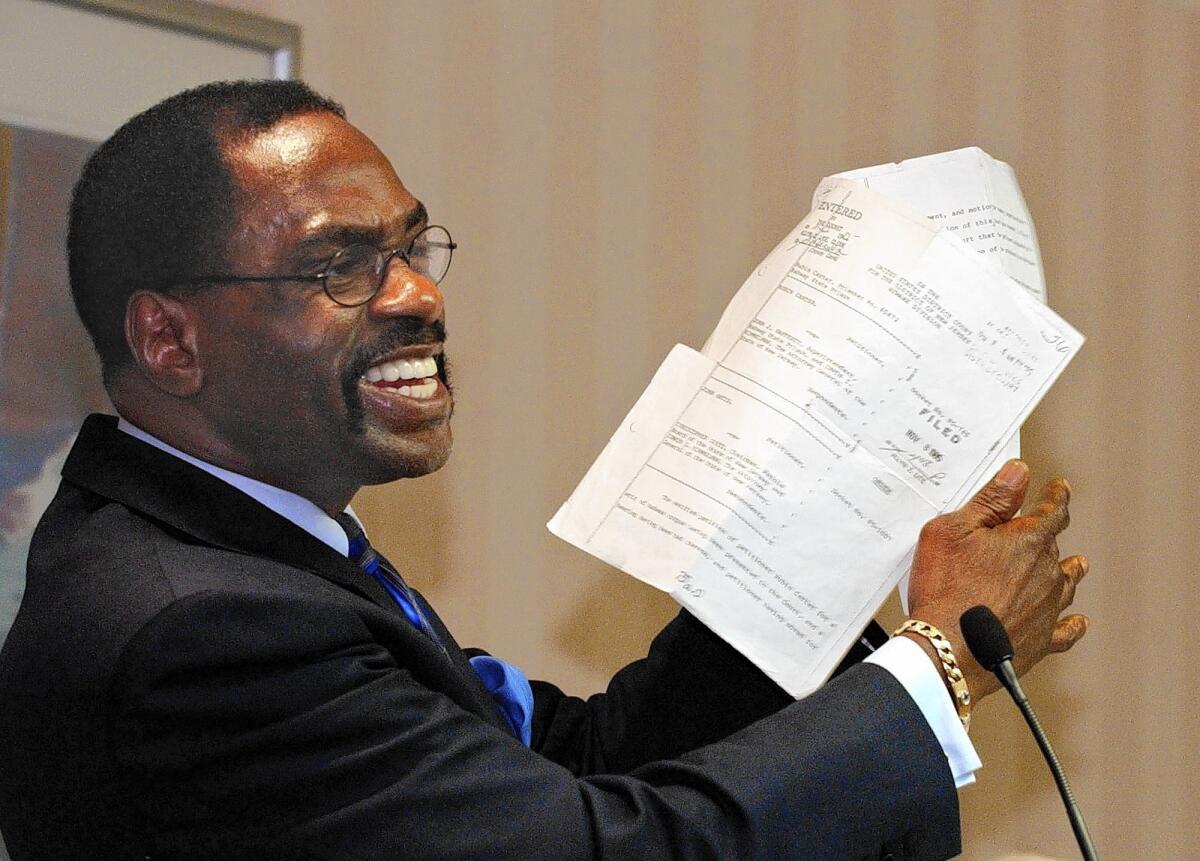

But, despite an explosive temper and a tendency to brag about acts like stabbing a man “everywhere but the bottom of his feet” when he was 14, Carter successfully fought the system that wrongly imprisoned him for 19 years. Convicted with a codefendant of three 1966 New Jersey barroom murders they did not commit, Carter was the subject of a Dylan anthem and a 1999 film starring Denzel Washington. Nobel laureate Mandela wrote a foreword for Carter’s 2012 memoir “Eye of the Hurricane.”

“Rubin woke up in prison and became a free man,” Mandela wrote. “His rich heart is now alive in love, compassion, and understanding.”

Carter died Sunday at his home in Toronto, Canada. He was 76.

Carter had been battling prostate cancer for three years, said Win Wahrer, an official with the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, a group Carter headed from 1993 to 2004.

“He was a complicated man but very inspirational,” Wahrer said. “He was the voice of the wrongly convicted when they didn’t have one.”

Carter’s example inspired Bernard Hopkins, the light-heavyweight world champion who at 49 won a key title bout Saturday.

During his incarceration for strong-arm robbery from 1984 to 1988, Hopkins learned of Carter and always wondered how “the bald-headed, black man in America at that time” persevered.

“That was a profound way to fight,” Hopkins told The Times, “a profound way not to lie down, a profound fight for freedom.... There has to be a situation where redemption is always there as an option.”

After an all-white jury in Paterson, N.J., deliberated for less than two hours in 1967, Carter and an acquaintance, John Artis, were found guilty of fatally shooting a bartender, a waitress and a customer at the Lafayette Bar and Grill. Another customer was wounded but survived.

After they won an appeal based on two key witnesses recanting their testimony, a second jury convicted them again in 1976.

Artis, who was with Carter when he died, was paroled in 1981.

The next year, the New Jersey Supreme Court upheld the convictions, but defense attorneys appealed to the federal courts. Carter was released in 1985, after years of celebrity-studded benefits and a public relations campaign directed by top Madison Avenue adman George Lois.

In a blistering ruling, U.S. District Court Judge H. Lee Sarokin cited “grave constitutional violations.” He wrote that Carter’s prosecution was “predicated upon an appeal to racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure.”

Prosecutors contended that the Lafayette killings were racially motivated payback for the shooting of a black bartender at another bar earlier that evening.

They were found to have withheld a tape recording on which a witness was offered the possibility of a reward and lenient treatment for alleged crimes in return for testifying against Carter and Artis.

Born in Clifton, N.J., on May 6, 1937, Carter was the son of Bertha and Lloyd Carter, a stern Baptist deacon who beat him for minor infractions. The family was firmly middle class, with Lloyd working in a rubber factory and running an ice business.

But the son was often in trouble, lashing out at teachers and getting in fights. Sent to reform school after stabbing a man with a broken bottle, he ran away from the institution, joined the Army at 18 and was sent to West Germany, where he learned to box.

Equipped with a powerful left hook, Carter won 51 of his military bouts, 35 of them by knockouts. He lost only five.

After his discharge, he immediately plunged back into trouble with a series of violent muggings. After four years in New Jersey state prisons, the 5-foot-8 middleweight started his professional boxing career in earnest and was a huge success.

Although Carter wasn’t technically among the best, he was “a rough, tough guy — a big puncher,” said Don Chargin, who promoted fight cards at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles.

“He really had the intimidation thing down,” Chargin said. “He was a showman.”

In Paterson, he played his role to the hilt, sporting fine suits, berets and Italian shoes. He drove an Eldorado with his name inscribed over each headlight and rode a horse in his 10-gallon hat.

Carter was “hard to miss passing the white families picnicking on the hillside, and he didn’t mind when his riding partner was a white woman,” wrote James S. Hirsch in his 2000 biography, “Hurricane.”

Hours after the Lafayette Grill killings on June 17, 1966, Carter and Artis were questioned by the police after a witness said they’d been nearby. They were released but then arrested four months later.

Friends and family members were shocked.

“They believed he was capable of killing three people but not in the fashion of the Lafayette bar murders,” Hirsch wrote. “The rules of the street were clear: Punks and sissies used guns or knives. Warriors used their fists.”

Police found no murder weapons or incriminating fingerprints. Officers “pressured two petty criminals who were committing a burglary down the street,” wrote Lewis M. Steel, one of the pair’s defense attorneys, in a 2000 Times article. “To bolster their case, police planted a bullet and a shotgun shell in Carter’s vehicle.”

In the racially charged late 1960s and 1970s, the case drew national press attention. In 1974, the New York Times criticized police and prosecutors in an extensive front-page article. Carter himself published a book, “The Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472.” The next year, Dylan came out with his tribute, “Hurricane,” whose lyrics are still quoted in law school classes.

“That’s the story of the Hurricane

But it won’t be over till they clear his name

And give him back the time he’s done

Put him in a prison cell but one time he could-a been

The champion of the world.”

In prison, Carter flouted rules — he refused even to carry an ID card — and immersed himself in books on religion, philosophy and metaphysics. He drew legions of outside followers, including members of a Canadian commune who asked him to join upon his release.

He married its leader, Lisa Peters, but their marriage fell apart in the early 1990s.

Denzel Washington received an Academy Award nomination for his portrayal of Carter in “The Hurricane.” The film was criticized for its Hollywood treatment of Carter’s real-life story, including soft-pedaling his criminal past.

Carter was married twice. He and his first wife Mae Thelma had a son and a daughter during their marriage, which ended in divorce.

Traveling across the U.S. and Canada on behalf of the exoneration cause, Carter sounded a more mellow note in his later years than in his turbulent past.

A Toronto resident since 1988 and a naturalized Canadian citizen, Carter told the New Yorker in 2011 that he preferred life north of the border.

“I don’t feel comfortable in the U.S. at all,” he said. “People are too mean, too hot-tempered, too ready to believe things that don’t exist. I’d rather be around people who are polite.”

Times staff writer Lance Pugmire contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.