Thomas Kinkade dies at 54; ‘Painter of Light’ worked to project ‘serene simplicity’

- Share via

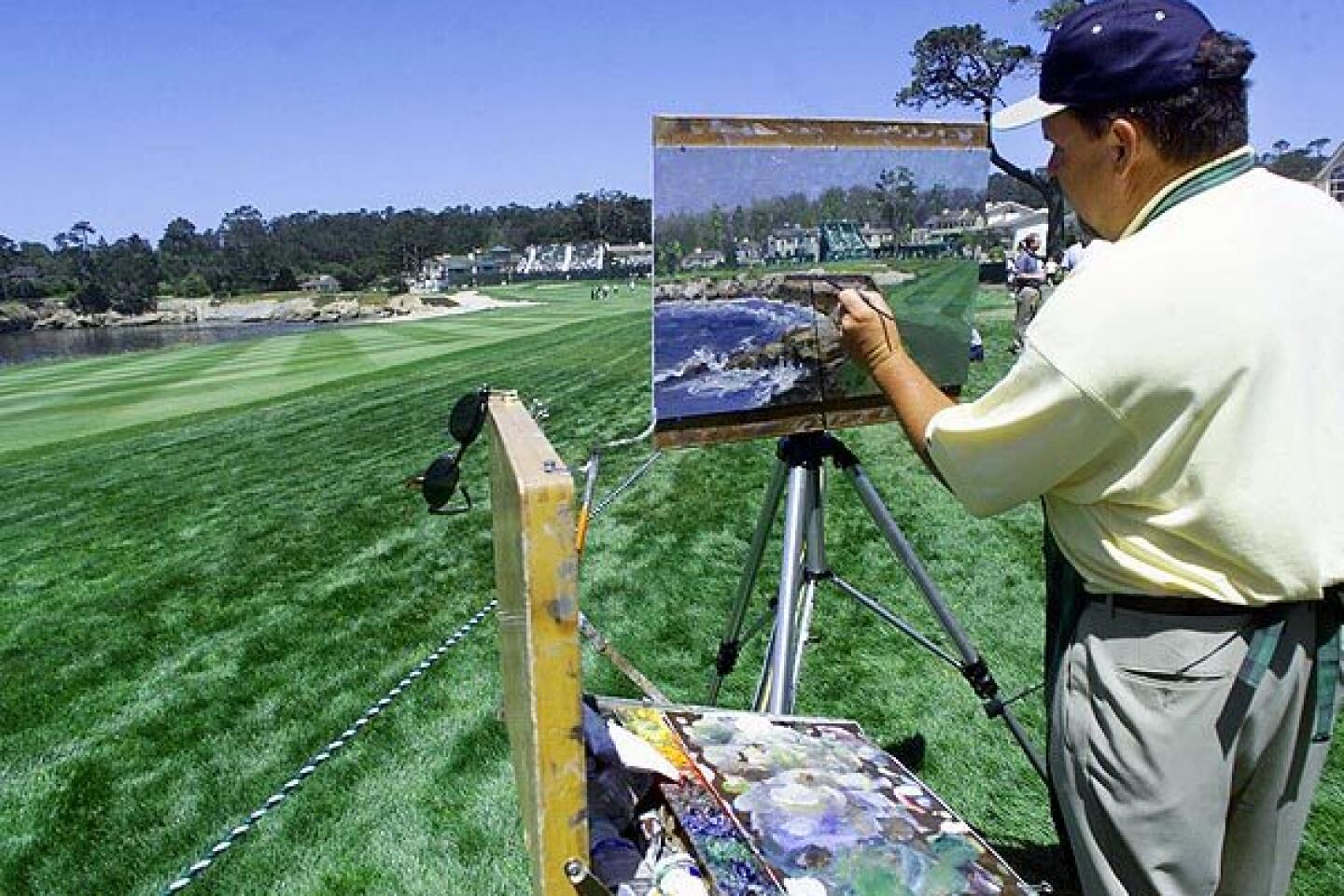

Thomas Kinkade, the self-styled “Painter of Light” who died Friday at 54, once said he worked to “create images that project a serene simplicity.” But despite his astonishing commercial success with luminous seascapes and paintings of cottages and street scenes, Kinkade’s life in many ways was neither serene nor simple.

Millions of his paintings and prints hang in homes around the world, popularity that translated to more than $50 million in earnings for the artist from 1997 to 2005 alone. Lauded for his generosity, he once gave an Anaheim widow $25,000 worth of his art to replace what she’d lost in a fire.

“He lived life to the fullest,” said Ken Raasch, his former business partner who co-founded Kinkade’s company more than 20 years ago. “He was a very eclectic character, an amazing artist who was not a stereotypical man in any sense. He created his own mold, I’d say, and I think we were all blessed because of that.”

Kinkade’s fame and fortune, however, were complicated by personal and business struggles.

In the last decade he had been locked in legal battles with former Thomas Kinkade Signature Gallery owners, some of whom accused him in lawsuits of trading heavily on his Christian beliefs even as he drove them to financial ruin.

He had battled alcohol abuse, former business associates said in court records and interviews, and in 2010 his mug shot went viral after his arrest on a drunken driving charge to which he later pleaded no contest.

And for more than a year, Kinkade had been separated from his wife, Nanette, with whom he had four daughters.

“The Thomas Kinkade story and legacy is a story of triumph and tragedy, which I believe that everyone can gain from paying attention to,” said Terry Sheppard, a former Kinkade friend and company vice president who parted ways with the painter in 2003.

Kinkade died Friday at his home in Monte Sereno, an affluent enclave near Los Gatos in the Bay Area. His family attributed his death to natural causes. The Santa Clara County coroner planned to conduct an autopsy Monday.

“Thom provided a wonderful life for his family,” his wife, Nanette Kinkade, said in a statement. “We are shocked and saddened by his death.”

In addition to his wife, he is survived by their daughters, Merritt, Chandler, Winsor and Everett, and a brother, Pat, who worked for Kinkade’s company.

On Saturday, Thomas Kinkade Co. officials sent a message to distributors that the business will continue, saying that “his art and powerful message of inspiration will live on.”

He was born William Thomas Kinkade III in 1958 in Sacramento County and often said he was the product of a broken home and a rough childhood.

Kinkade once worked as a film animator and sold his paintings in supermarket parking lots in his hometown of Placerville. More than two decades ago, he and his wife spent their life savings to start his printmaking business.

Since then, Kinkade became wealthy painting his romantic, idealized images of landscapes, lighthouses and country cottages with windows aglow. His images also have adorned air fresheners, night lights, teddy bears, toys, pillows andLa-Z-Boyloungers.

Some critics have dismissed Kinkade’s works — with titles such as “Silent Night” and “The Garden of Prayer” — as mass-produced kitsch. But that has not kept legions of admirers from paying from as little as $99 for a print to $10,000 or more for canvas editions signed and retouched by the artist.

Karen de la Carriere, a Los Angeles dealer who specializes in Internet resales of Kinkade’s work, said her business “spiked like never before” after Kinkade died.

In a 2006 Times interview, she had likened Kinkade to “a modern-day Leonardo da Vinci or Monet.” On Saturday, De la Carriere said that she would remember him for his talent and charitable works.

“A lot of people try to slime Thom, saying his art is just mass-produced for the money,” she said. “But Thom had a really generous side. I knew a lady whose entire house burned down. When he found out about it and that she was ... a widow who had lost her nine Kinkade images, he replaced them.”

Others’ memories of Kinkade, touted as one of America’s most widely collected artists, are harsher.

In 2006, an arbitration panel ordered Kinkade’s company, then called Media Arts Group, to pay $860,000 for defrauding the former owners of two failed Virginia galleries. The lawsuit, like those brought by other failed dealers, alleged that the company had used Kinkade’s religious faith to draw them into the business, and then stuck them with unsalable merchandise and forced them to open stores in markets that couldn’t sustain them.

The fraud finding did not single out Kinkade but said that he and others at the company created “a certain religious environment” designed to get prospective gallery owners to trust the company.

The $860,000 award was later increased to $2.8 million to cover interest and legal fees.

Kinkade agreed to pay the award after moving vans hired by the plaintiff’s lawyer, Norman Yatooma, showed up at one of Kinkade’s companies, Pacific Metro, threatening to take artwork to satisfy the judgment. The company had made one $500,000 payment and was due to pay an additional $1 million when it abruptly filed for bankruptcy protection, halting further payment. A new payment plan was worked out in the bankruptcy, Yatooma said Saturday.

“Running a charity that supports fatherless kids, and as a father of four daughters myself, my heart sincerely breaks for Thomas Kinkade’s family,” he said. “My heart also breaks for the lives of the countless other families that Thomas Kinkade’s company has devastated. Regrettably, my perspective of Thomas Kinkade was much more of a misled businessman than an accomplished painter.”

In sworn testimony and interviews with The Times, former gallery owners and ex-employees recounted incidents that made Kinkade’s personal behavior appear at odds with his Christian image.

The recollections included an allegedly drunken Kinkade heckling illusionists Siegfried & Roy in Las Vegas and cursing a woman who tried to help him when he fell from a bar stool.

The artist later accused “disgruntled ex-dealers” of launching “media attacks” on him. But he also said he might have behaved badly during a stressful time that he had since put behind him.

He also once testified the he was not perfect, and never claimed to be.

“Book of Ecclesiastes says enjoy yourself, have a glass of wine, for this is God’s will for you,” he said. “It’s never consistent with God’s will that we behave in a sinful way; however, God also loves us and accepts us and understands that at times we have our failings.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.