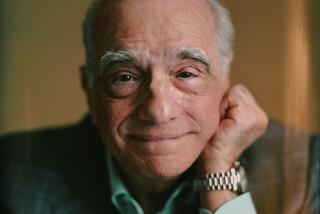

Eugene Genovese dies at 82; leftist historian turned conservative

Eugene D. Genovese became one of the most notorious radical intellectuals in the country in 1965 when he addressed an all-night teach-in at Rutgers University on the Vietnam War.

“I do not fear or regret the impending Viet Cong victory. I welcome it,” the self-described Marxist historian declared, setting off a furor that had politicians such as Richard Nixon demanding his dismissal.

An academic witch hunt ensued, but the onetime Communist Party member held to his political beliefs for decades. He freely admitted that Marxist ideas informed what became his most influential work: a 1974 study of slaves and slave masters in the antebellum South called “Roll, Jordan, Roll.”

In the 1990s, however, the staunch leftist evolved into an unfaltering conservative. He called on fellow leftists to repent, disavowed his long-held atheism and condemned political correctness.

Genovese, whose political and religious transformation added a mercurial twist to a distinguished career, died of natural causes Sept. 26 at his home in Atlanta, said his friend William J. Hungeling. He was 82.

“There seemed to be no middle ground,” Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon Litwack said of Genovese, whom he knew well and considered one of the most important American historians. “In some ways he was always an ideologue, whether of the left or, ultimately, of the right. But he was always open to the voices of others. I found him to be exhilarating company.”

During an academic career that spanned five decades, Genovese wrote several highly regarded books on the history of slavery, including “The Political Economy of Slavery” (1965) and “The World the Slaveholders Made” (1969). He also co-wrote “The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders’ Worldview” (2005) with his wife, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, a noted historian and pioneer of women’s studies who also moved rightward in later years.

Of his dozen books, “Roll, Jordan, Roll” was the most honored, winning the Bancroft Prize for American history in 1975. The book revised the traditional view of slave life as unrelentingly brutal and degrading, portraying instead a more complex relationship in which slaves, by accommodating their masters’ paternalistic ethos, gained some control that prevented their own dehumanization. The masters, in turn, needed their slaves’ gratitude to see themselves as moral beings.

Relying heavily on interviews with former slaves conducted in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, the book was the product of a decade’s labor and inspired the admiration of rival historians such as Litwack, a UC Berkeley emeritus professor who was writing his Pulitzer-winning work on Reconstruction during the same period in the 1970s.

“I felt after reading his book that few if any historians had such a grasp of the day-to-day relationships between whites and blacks, between the master class and slaves, on the plantation,” Litwack said last week. “He gave slaves a certain amount of humanity they had not been given before by other historians.”

The book had its critics, who faulted Genovese’s analysis as “too admiring of the slaveholders’ power and too dismissive of the slaves’ rebelliousness,” Steve Hahn, another Pulitzer Prize-winning expert on slavery who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in the New Republic last week. . But Hahn concluded that “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” with its broad scope and literary touches, “may well be the finest work on slavery ever produced.”

The son of an immigrant Italian dockworker and his homemaker wife, Genovese was born in New York City on May 19, 1930. He joined the Communist Party at 15, but his disregard for party orthodoxy caused his ejection a few years later.

He joined the Army after receiving a bachelor’s degree from Brooklyn College in 1953, but his service was cut short when superiors learned of his Communist past. He earned a master’s in history in 1955 and a doctorate in 1959 from Columbia University.

In 1963 he joined Rutgers. His controversial remarks about the Viet Cong came in the midst of New Jersey’s fall 1965 election season and became campaign fodder for the Republican candidate for governor and Nixon. “Let me brag,” Genovese wrote years later. “So far as I know, I remained the only professor in America whom Richard Nixon personally and publicly campaigned to get fired.”

Although he had tenure, Genovese left Rutgers in 1967. Over the next decades he taught at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, the University of Rochester, the College of William and Mary and several universities in Georgia, including Emory University. He also had appointments at Columbia, Yale and Princeton.

In 1969 he was 39 and twice divorced when he married Fox, a 28-year-old graduate student. They became what Christopher Hitchens later described as “the royal couple of the academic left.” An expert on the history of Southern women, she established the nation’s first doctoral program in women’s studies at Emory. With her husband she co-founded the short-lived journal Marxist Perspectives.

By the early 1990s, a shift was clearly in progress. Fox-Genovese wrote books that signaled major disenchantment with feminism. Her husband wrote a scorching 1994 essay for Dissent magazine titled “The Question,” which called on fellow leftists to acknowledge their support of brutal socialist regimes. Time magazine covered the resulting brouhaha, quoting Genovese saying he considered “the communist movement dead and socialism finished.”

In 1995, Fox-Genovese went to church alone, afraid to tell her nonbeliever spouse she was going to receive the sacraments of Roman Catholicism. After her conversion Genovese kept her company at Mass. In 1996 he embraced the religion and remarried his wife in a Catholic ceremony.

Genovese, who had no children, wrote of her affectionately in “Miss Betsey: A Memoir of Marriage. “ It was published in 2009, two years after her death from a long illness.

The book opens with an account of their first date, when she was recovering from hepatitis and anorexia. “Having expected a good-looking young woman, I came face to face with Death Warmed Over,” he wrote. “How could Death Warmed Over have so breathtaking a smile?”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.