Ian Barbour dies at 90; academic who bridged science-religion divide

- Share via

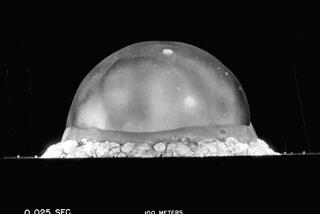

For Ian Barbour, the deadly possibilities of the Atomic Age raised questions that science couldn’t answer — a perplexing situation for a young physicist after World War II.

He responded to the challenge in an unusual way: After completing his doctorate in physics he enrolled in divinity school and forged a career devoted to bridging the chasm between science and religion.

Barbour, whose work opened a new academic field and brought him the prestigious Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion died at a hospital in Minneapolis on Christmas Eve, five days after a stroke, said his son, John Barbour. He was 90.

A professor at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., for more than three decades, Barbour wrote 16 books, including “Issues in Science and Religion,” a 1966 volume that helped spark the ongoing debate between scientists and theologians on issues such as the origins of the universe, evolution and the ethical implications of technology.

He “gave birth almost single-handedly to the contemporary dialogue between science and religion,” said Robert John Russell, the founder-director of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, a nonprofit teaching and research institute affiliated with UC Berkeley’s Graduate Theological Union. “He made a convincing and lasting case that science and religion are more alike and analogous than unlike and conflictive.”

In the 1950s, when Barbour began to promote discourse between the two fields, scientists had little tolerance for religion, and theologians had little interest in science. His was a lonely voice for rapprochement.

“I always felt we needed to move beyond the hostility,” Barbour told The Times in 1999. “Scientists say they believe in evolution, not God. Religious scholars say they believe in God, but not evolution. Well, I say we don’t have to choose a side. We can meet somewhere in the middle.”

He received the Templeton Prize in 1999 for a lifetime of work that judges said helped expand the field of theology. He gave most of the $1.24-million award to the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences.

His views about the commonalities between religion and science were criticized by such prominent scientists as Stephen Jay Gould. But Barbour’s advocacy made inroads at such leading organizations as the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science, which in the mid-1990s launched a program to improve communication between religious and scientific communities on matters such as environmental stewardship and life beyond Earth.

“Scientists particularly have appreciated the humble and insightful ways he has considered how we imagine and model the unknowns in each realm,” said Jennifer Wiseman, director of the association’s Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion.

Born in Beijing on Oct. 5, 1923, Ian Graeme Barbour was one of three sons of his American Episcopalian mother and his Scottish Presbyterian father, both of whom taught at Yenching University. (His father, George, was a distinguished geologist involved with the group that discovered the early human remains known as Peking Man.) The family left China in 1931 and spent a few years in England before settling in the United States.

Barbour earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Swarthmore College in 1943. Exposed to Quaker thought during college, he became a conscientious objector who spent World War II fighting forest fires in Oregon and working with mental patients in North Carolina.

After obtaining a master’s degree in physics from Duke University in 1946, he went for his doctorate at the University of Chicago, where he was a teaching assistant for Enrico Fermi, the Manhattan Project scientist responsible for the world’s first atomic chain reaction.

He earned his doctorate in 1949 and joined the physics faculty at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, where he found himself increasingly drawn to the ethical and theological implications of scientific discoveries. With a Ford Foundation fellowship, he studied theology, ethics and philosophy at Yale Divinity School and earned a divinity degree in 1956.

Before completing his divinity studies, he accepted an offer from Carleton College to teach physics and religion. In 1960 he founded its religion department and began to write about issues of concern to both scientists and religious thinkers.

“What had started as an attempt to fit together two halves of my own life had become a wider intellectual inquiry in which I found that many other people were interested,” he wrote in an autobiographical essay.

In 1989 and 1990 he gave Scotland’s prestigious Gifford Lectures, an annual series of talks on natural theology whose presenters have included Albert Schweitzer and Reinhold Niebuhr. Barbour’s lectures were turned into two books, “Religion in an Age of Science” (1990) and “Ethics in an Age of Technology” (1993).

In his acceptance speech for the Templeton Prize, Barbour spoke of the urgent need to break down barriers, offering cloning as an example of the ability of science to tell society what is possible and of religion to reflect on what is desirable.

He also challenged people to reconsider the biblical view of death as a punishment for human sin.

“Now we know that death was present long before human beings were around, and that it was a necessary feature of an evolutionary process in which new forms of life could appear,” he said. “We can take the Bible seriously without taking it literally.”

Barbour’s wife of 64 years, Deane Kern, died in 2011. He is survived by four children, a brother, three grandchildren and a great-grandson.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.