Drug kingpin ‘El Chapo’ creates a rush for LA clothing firm’s shirts

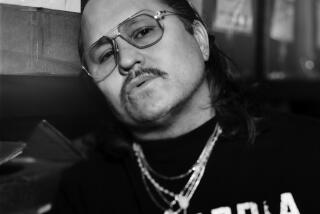

Sam Esteghball, CEO of clothing retailer Barabas, with the company’s Fantasy shirt, the same style worn by Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman in a widely distributed photo of him shaking hands with actor Sean Penn.

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s fashion sense has catapulted a Los Angeles men’s clothing company to new heights after the Mexican drug lord was photographed wearing two of the firm’s shirts in an interview with Sean Penn for Rolling Stone magazine.

Shortly after the article was published this month, Barabas’ wholesale customers began to call the company when they recognized the brand’s bright colors and bold patterns. Since then, Tatiana Kivachook and her husband, Sam Esteghball, one of the business’ owners, have been working more than 12 hours a day with little time off just to keep up with the demand for the El Chapo shirts.

“This sudden madness — I cannot call it anything different,” said Kivachook, vice president of the company. Esteghball, her husband, is chief executive.

In a matter of hours, the wholesale clothier with eight employees went from receiving 10 to 20 orders a day to hundreds. The phones rang endlessly, and the website crashed after the volume of orders overwhelmed the server.

TV crews lined up outside the company’s wholesale storefront and nearby open-to-the-public showroom in the Fashion District to get a shot of the shirts.

“In the beginning, it was like a panic,” Kivachook said.

Two weeks after the article was published, the blue shirts with floral and paisley patterns are still on back order with an expected shipping date between Sunday and Feb. 5. They sell for $128 on Barabas’ website, but can go for as much as $500 on eBay.

The company is hiring additional workers, especially in customer service, to handle the orders that are streaming in from around the world. The duo, buoyed by unexpected attention, is looking for a strategic partner to help open retail stores. Barabas’ clothing is mostly found in boutiques and mom-and-pop shops.

Even Kivachook is unsure why the shirts have become so popular and why it has continued for so long. She said she thinks customers are interested because the shirts are brighter than the drab-colored clothes usually marketed toward men, and because of the statement of power it represents.

Angel Garcia, 41, made a 30-minute trip after work last week to a showroom in downtown LA to try to purchase the “El Chapo” shirts. He said he was thwarted by the back order and the computer system, which was down because of the high volume of orders.

“It’s not that I approve what he does,” Garcia said. “He’s so popular, and I want to have that shirt, that’s all. I love the design, the color.”

Instead, he walked away with three other Barabas shirts — one blue, one brown and one with a pink-and-brown pattern. He said he has never shopped at Barabas before, but will be returning because he likes the feel and design of the shirts. He said he’ll try again later to get the Crazy Paisley and Famous styles sported by Guzman in Rolling Stone.

The company hasn’t shied away from its infamous customer. Images of the shirts flash across the Barabas website, labeled “Most Wanted Shirt.” At the company’s wholesale location, two headless mannequins model the shirts in front of passers-by.

But Barabas makes clear that it has no ties to Guzman.

“We have never met Joaquin Guzman, a.k.a. El Chapo,” the company says on its home page, attributing the drug kingpin’s “boldly crafted” sartorial choice to the “comfort, quality and style that (the) Barabas shirt projects.”

The garment-makers have no idea how Guzman became familiar with their products, but Barabas has a bigger market in Mexico than in the U.S. Its clothing can be found in shops and at a trade show in Guadalajara. Many musicians and bands have bought the company’s shirts, Kivachook said, and some of their photos paper a back wall at the garment firm’s wholesale location.

The 8-year-old company’s motto — “good words, good thoughts, good deeds” — is emblazoned on an awning outside its wholesale shop.

“We’re trying to bring some color into men’s fashion and to bring some emotion,” Kivachook said. “Clothes don’t have to be clothes. They can be an artistic masterpiece that can define you and your personality.”

She said the clothier plans to donate 5 percent of the profits from the El Chapo shirts to the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program that was founded by the Los Angeles Police Department in the early 1980s.

“We’re trying to help educate children on drug issues,” Kivachook said. “We’re trying to create something good.”

samantha.masunaga@latimes.com

Twitter @smasunaga

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.