A mother risked her life to reunite with her kids in the U.S. Now she faces prison time

In the weeks after her deportation, Mayra Machado sat alone in a dark room, staring at her phone.

In video chats, her three children battered her with questions. Where was she? Why had she abandoned them? When would she come home to Arkansas?

She couldn’t bear to tell them the truth — that she was in a remote village in El Salvador overrun with gangs — so she lied. “I’m fine,” she said. “I’ll be home soon.”

The United States deports hundreds of thousands of immigrants each year. But for Machado and other parents of American-born children, staying in their home country sometimes simply isn’t an option, despite the risk.

To keep her promise to her kids, Machado had to embark on a dangerous journey abetted by abusive smugglers linked to a powerful drug cartel.

She would eventually make her way back to the sleepy town of Siloam Springs, Ark., but a reckless decision from her youth — and a little-known feature of American immigration policy — would threaten to separate her family yet again.

Machado was 5 when she and her mother crossed illegally to the United States, fleeing bombings in their village during the final years of El Salvador’s civil war.

She grew up speaking English with a laid-back California accent during her youth in Santa Ana. Later, after she and her mother moved to be near family in Arkansas, she adopted a gentle Southern drawl. She loved shopping and football and moved through life with a cheerful American optimism.

At age 19, Machado made a foolish mistake. After she fell behind on loan payments, her car was impounded. To get it out, she forged a friend's signature on two checks totaling $1,500.

She was found guilty of three felonies and, after completing a court-ordered boot camp program, vowed to never mess up like that again.

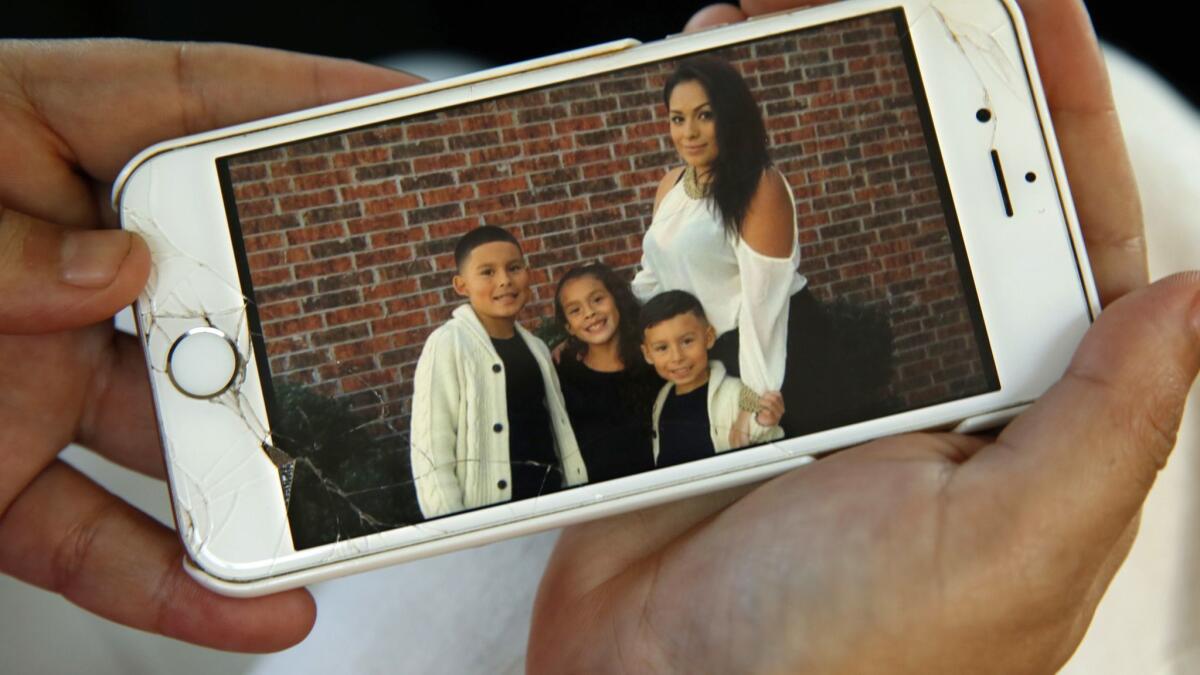

A decade later, Machado said, she had turned her life around. She worked at an ophthalmologist’s office, drove a BMW and had three photogenic kids. The father of her children was out of the picture, but Machado had met a kind man with a good job and they were engaged.

Shortly before Christmas in 2015, a routine traffic stop changed everything. Because she had an unpaid ticket, Machado was taken to a police station. There, an officer deputized to act as an immigration agent discovered Machado’s felony convictions and began the process that led to her deportation.

Unlike previous administrations, which had often targeted immigrants for deportation using arbitrary traffic checkpoints or workplace raids, President Obama had vowed to prioritize removals only of people with criminal convictions, saying he would target “felons not families.” Machado thought she had paid her debt to society but discovered that as an immigrant in the country illegally, she didn’t have the luxury of making mistakes.

After fighting her case for 13 months, Machado was deported in January 2017. She arrived in El Salvador in shackles on an Immigration and Customs Enforcement plane.

Distant relatives had offered her a place to stay in the rural hamlet of Hacienda La Carrera, but her broken Spanish and American clothing made her a target. Many homes had been abandoned by residents fleeing gangs that levied “taxes” on locals and forced pretty women to be their girlfriends. In an interview in the village last year, Machado said machete-toting gang members had begun loitering outside.

Still, what kept her up at night, as she listened for occasional bursts of gunfire and swatted away the mosquitoes that bit her arms and legs raw, was fear for her children: Dominic, 12; Dyanara, 11; and Dorian, 8. They were living in Siloam Springs with their grandmother, who rose before dawn to work at a meat-packing plant.

Dominic still didn’t know where she was but blamed himself for his mother’s disappearance. At the time of the 2016 traffic stop, Machado had been returning to the store where he had left his eyeglasses.

The bright, outgoing boy, who shared his mother’s wide smile and almond-shaped eyes, had become withdrawn during the months Machado spent in immigrant detention. He had started lashing out at his younger sister. His grades were slipping.

Machado knew the dangers of trying to return to the United States. But, she told herself, she was a mother, and mothers are supposed to be with their kids.

So one morning in March 2017, less than three months after she was deported, Machado woke at dawn and trudged through miles of sugar cane fields toward a narrow highway, where she caught the first of many buses north.

She was finally nearing the U.S. border when a smuggler put a gun to her head.

Machado had been on the migrant trail for weeks, hiding from authorities in taxi trunks and crowded tractor-trailers. She had gone days at a time without eating and had begun dreaming about what it would feel like to take a shower.

But only now, as the smuggler cocked his gun, did she realize the danger she was in.

“I’m in the hands of the Gulf cartel,” she thought. And then: “I might die, and my children will never see their mother again.”

Machado had used $8,000 of her savings to pay a smuggling network that had promised a short journey to the United States. But arriving that April in Tamaulipas, the northern Mexican state where drug gangs had entered the human trafficking business, it didn’t matter that Machado had paid all that cash weeks before. The smugglers said she would have to wait to cross the border until they were ready.

At a dingy safe house filled with dirty mattresses, Machado was made to cook and clean. She knew nothing about Mexican cuisine, and when she messed up while making salsa, the men threw it in her face.

“You’re fat and lazy!” screamed one cartel member as he beat her. Twice, Machado said, she fought off his attempts at rape.

After months in captivity, the smugglers helped Machado cross the border. It was the Fourth of July, 2017.

Two family members picked her up in Texas and drove all night to Arkansas. Shortly before sunrise, she opened the door to the bedroom where her children were sleeping and woke them up with hugs.

“I’m dreaming,” they murmured.

“No,” she said. “I’m really here.”

Back in Arkansas, Machado knew she had to earn back the trust of her children. Dominic had made that clear.

“Why did you have to go away?” he would ask on the days that he spoke to her at all.

For so long, she had lied. Finally, she decided to tell him the truth.

“I wasn’t born here, and I don’t have citizenship,” she said. Then she told him about the forged checks: “It was the worst mistake of my life.”

Machado opened a map, pointed to El Salvador and showed Dominic the more than 2,000 miles she had traveled. Dominic asked if she was going to disappear again. She shook her head.

In March of this year, she and the kids moved in with her fiance, Tony, whom her youngest son had started calling Dad. But she still lived a life in the shadows. Machado didn’t have an ID. Didn’t have a job. On the rare occasions she drove, she scanned the rearview mirror for police.

On a hot afternoon in May, she took the risk of picking up her daughter, who had just completed fifth grade. At a roundabout, the car in front of her stopped suddenly. Machado didn’t.

The woman’s Mercedes was not badly damaged, and Machado offered to pay on the spot for repairs. But the driver was angry and called the police.

Machado panicked. She phoned her best friend, who urged her to flee. That would be wrong, Machado said.

“OK,” her friend urged. “When the police come, give them my name instead of yours.”

That’s what Machado did, but the officer grew suspicious. Why didn’t Machado’s photo flash on his screen when he typed her name into his system?

When he threatened to call a fingerprint expert, Machado started crying. “My name is Mayra,” she said.

The officer charged her with a felony for obstruction of government operations. The charge was eventually dropped, but by then Machado had been flagged by ICE, and she was once again taken into immigration custody.

Only this time, she would be charged with a more serious crime.

The Washington County Detention Center in Fayetteville, Ark., is a cluster of low-slung buildings in a suburban office park. Machado has been living there for months alongside women charged with federal crimes that include drug trafficking and murder.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the U.S. government stepped up the criminal prosecution of immigrants, reversing its longtime practice of treating immigration offenses as civil matters. Machado is one of thousands of immigrants who have been charged this year with the felony crime of reentering the U.S. after a previous deportation.

Her court-appointed attorney has asked Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican whose reelection campaign has been endorsed by President Trump, to pardon Machado for the check forgery, in hopes of eliminating the rationale for deporting her. A grass-roots campaign has also taken up Machado’s cause, recently holding a rally outside the Arkansas prison where activists chanted “Free Mama Mayra!”

If those efforts fail, Machado faces up to two years in prison — followed by a second deportation.

The idea of remaining behind pains her, but it is less scary than the idea of being immediately deported again. “At least I’ll be safe in prison,” she said.

Machado has been prescribed medication for anxiety and depression, but in phone interviews from prison, she said she still cries all day. Her only respite, she said, is a twice-weekly Bible study class — and books.

She’s trying to be a mother from afar, speaking on the phone at a cost of 50 cents a minute.

“Who will do my hair when you’re not here?” her little girl asks. “I want to cuddle with you,” her youngest son says.

Dominic doesn’t speak much. He spends much of his time on his PlayStation. But recently, on a phone call, he told his mother, “If you go away again, it will break my heart.”

If she is eventually deported, she would not bring the kids to El Salvador, not with the gangs.

“What if they looked at my daughter the way they looked at me?” she wonders. “Would my son become one of them?”

Machado wonders, too, if she will be able to stay in El Salvador, or if she will try to reach the U.S. once again.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.