Confederate flag has new meaning for many Southerners since Charleston slayings

- Share via

Times are changing in the hearts of Dixie.

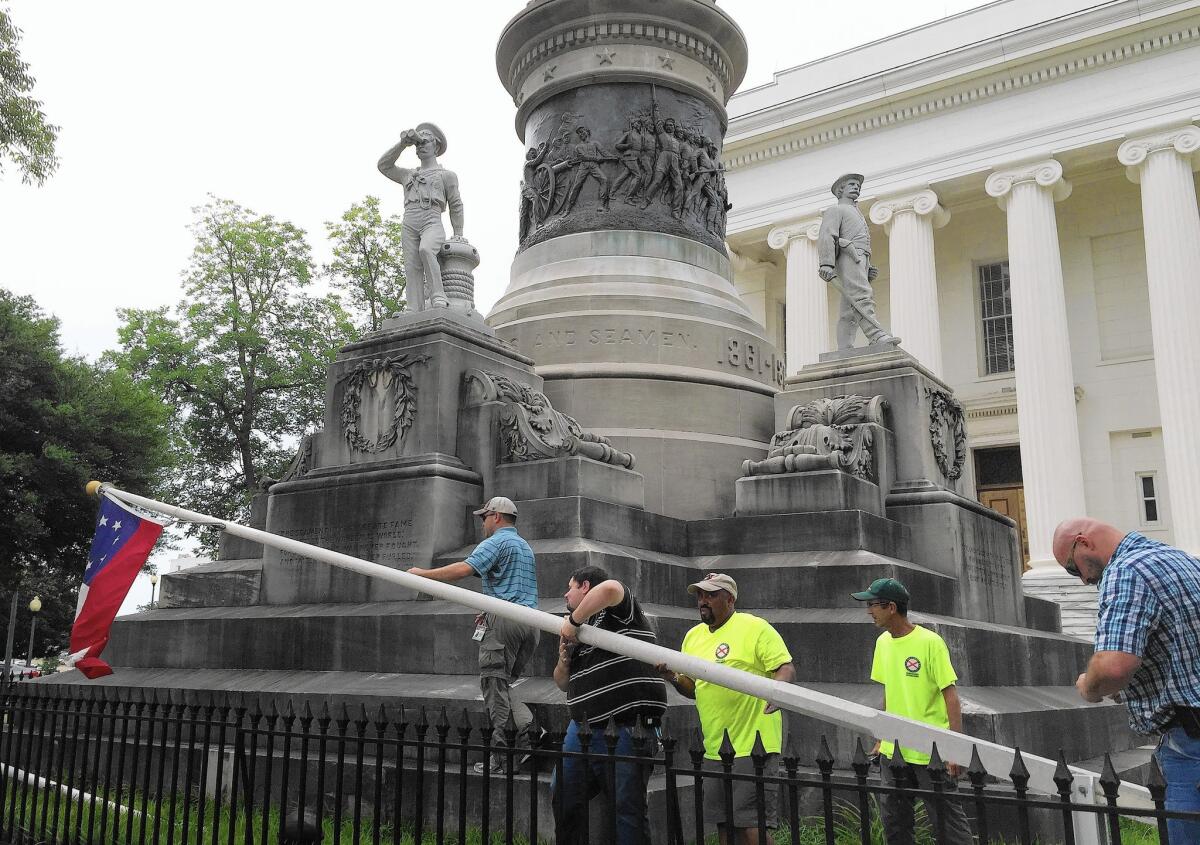

On Wednesday, Alabama Gov. Robert J. Bentley, a Republican, became the first Southern governor to use his executive power to remove four Confederate banners from a monument on the Capitol grounds. It was the latest step in the search for a safe spot between heritage and racism.

“It has become a distraction all over the country right now,” Bentley told reporters. The Confederate battle flag, which in modern times became a revered symbol to many in the South, “is offensive to some people because, unfortunately, it’s like the swastika,” he said. “Some people have adopted that as part of their hate-filled groups.”

This is a far cry from the time — just last week — when officials vigorously defended Confederate symbols as honoring what some saw as a glorious rebel past. But when a gunman — whom authorities identify as a young white supremacist who glorified the Confederacy — opened fire in a historic black church in Charleston, S.C., killing nine African Americans who were studying the Bible, that Southern worldview radically shifted.

In recent days, politicians in Virginia, South Carolina, Mississippi and Tennessee have questioned Confederate symbols including flags and statues, while top retailers such as Wal-Mart and EBay have said they will no longer sell Confederate flags, belt buckles, clothing and the like. Even the quintessential Southern sport of stock-car racing announced it was walking away from Confederate symbols.

“This is symbolism,” said James Forman Jr., a professor at Yale Law School who has written about race and the Confederate flag. “And symbolism matters.”

The fight over Confederate symbols is hardly new, but it took on added urgency after the shootings in Charleston, where Dylann Roof, 21, is being held on nine murder counts. Photos of Roof with Confederate symbols have surfaced along with racist documents mourning the loss of white domination.

The South is filled with memorials to the Confederacy, including parks, schools, college mascots, street names and statues of famous leaders at state capitols. The list seems as endless as the battles over the symbolism.

In recent years, Confederate flags sparked a fight in Georgia. There have also been controversies over the naming of parks for prominent racists, especially Nathan Bedford Forrest, a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army and the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Tennessee officials are again calling for removing his statue from state grounds.

In New Orleans a battle is brewing over the landmark column and sculpture dedicated to Confederate hero Gen. Robert E. Lee, located at Lee Circle on St. Charles Avenue. Statues of Jefferson Davis, the only president of the Confederacy, are an invitation to heated debates like the one underway about whether one such statue should be removed from Kentucky’s Capitol Rotunda.

“It makes sense that efforts to change Southern symbols comes on the heels of the Confederate-flag-supporting terrorism that killed nine people in Charleston,” said Ted Ownby, director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. But in a telephone interview, he argued for a broader view of history.

Many people look at the South’s history and see what historians call the “cavalier myth, an old idea that there was something distinctive about the Southern upper class.” That group, which included some of the U.S. Founding Fathers who owned slaves, saw itself as educated aristocracy.

That view of the South changed over the Civil War. The loss to the North and the following years spawned a vision of the Confederacy as a time of bravery and sacrifice in defense of the homeland. South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, a Republican, referred to those values when she described the Confederate battle flag as “a symbol of respect, integrity and duty” for those who consider it a memorial.

But Haley went on to call for the flag’s removal, noting: “This flag, while an integral part of our past, does not represent the future of our great state.”

While the Charleston killings may have been the immediate spark for change, questions about race and violence have been building, Ownby said. He traced the start to the Trayvon Martin case, which pushed the issue of violence against blacks to the forefront. During a 2012 confrontation in Florida, Martin, an unarmed teenager, was shot to death by George Zimmerman, who has described himself as a light-skinned Latino. Zimmerman was acquitted of second-degree murder.

Roof and other supremacists also cite the Zimmerman case as part of the reason they see whites as losing standing.

There has also been a range of cases in the last year involving police violence against blacks, from Ferguson, Mo., to Staten Island, N.Y., to Baltimore to North Charleston, S.C. Those, too, have kept the issue in the forefront and have provided a fertile background for change, Ownby said.

Forman also cited Charleston but looked beyond.

“People in South Carolina were not just horrified by what happened at Emanuel [African Methodist Episcopal Church], but were also moved by the kind of mercy and compassion and openheartedness that the victims of that crime showed in the aftermath,” Forman said. He also mentioned the slain pastor, Clementa Pinckney, a state senator whose body lay in state at the Statehouse on Wednesday.

“It’s clear that the personal relationship is critical here,” Forman said of Pinckney and the decision to remove the Confederate flag, which is pending in the state Legislature. “People knew this man and by all accounts respected him. So some of this is local.”

Forman also sees the decision on the flag as a gesture similar to efforts to remove racial slurs from public discourse.

“Symbolism is only part of the answer,” Forman said. “The same way the N-word has been retired, the flag has been retired. It’s not easy, but it is easier than dealing with access to voting, race in the criminal justice system and equal opportunity.”

Twitter: @latimesmuskal

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.