Lies, insults and exaggerations: A U.S. presidential campaign tradition

- Share via

This year’s presidential campaign has been described as outrageous, coarse, unfitting of a civilized country. But there might be another way to describe it: thoroughly American.

The United States is no stranger to scandalous and strange presidential elections. In fact, they were the norm in the country’s early years, when candidates resorted to invective that not even Donald Trump has equaled.

Presidential campaigns have evolved with developments in technology as well. Throughout the evolution, however, words — sometimes hyperbolic, insulting, even blatantly false — have always mattered.

1800: Early days and a vicious campaign

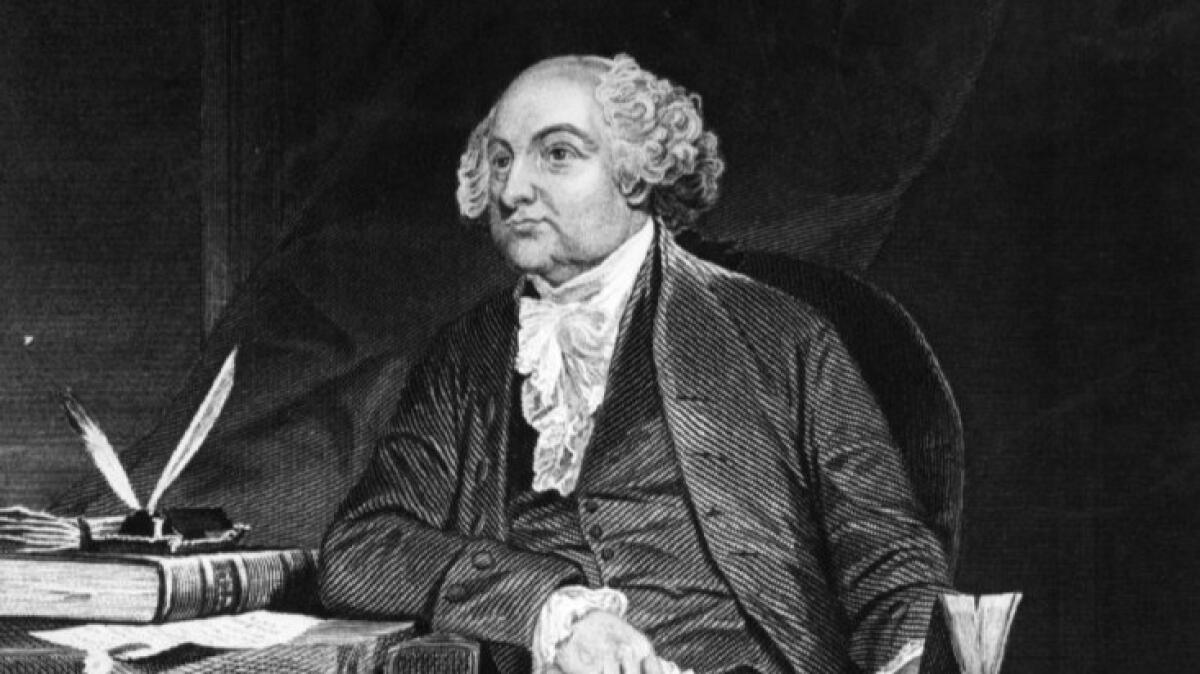

The presidential campaign of 1800 gave the American public its first taste of how outrageous and fierce candidates could be in pursuit of the highest office.

Thomas Jefferson, who lost the 1796 election against John Adams, campaigned formidably against the incumbent.

He paid the editor of the Richmond Examiner to print anti-Federalist and anti-Adams articles and praise his own campaign.

Written attacks by Jefferson supporters claimed Adams was a “hideous hermaphrodital character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

Adams’ campaign retaliated, calling Jefferson a “mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.”

1828: Round 2 of Jackson vs. Adams

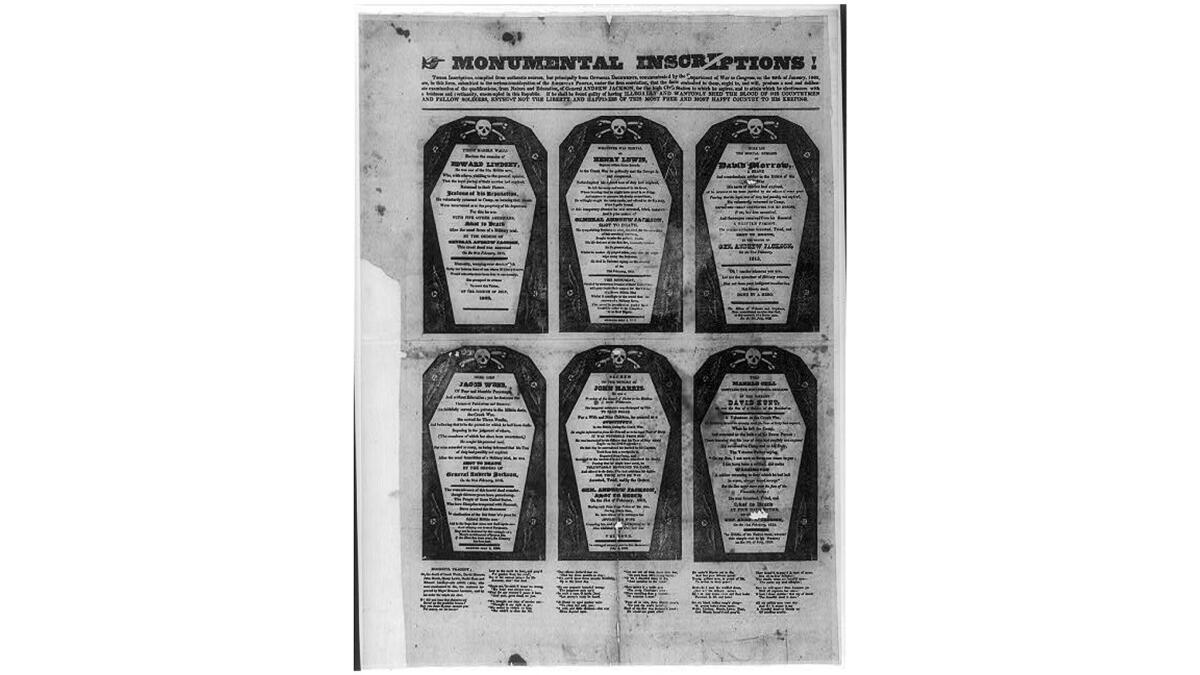

Andrew Jackson, a decorated Tennessee war hero, lost the presidential election of 1824 to John Quincy Adams. So there was bad blood between the two when Jackson challenged Adams four years later, in 1828. The race turned into one of the ugliest in the country’s history.

Jackson and his wife, Rachel, were vilified by Adams’ campaign. They were called “adulterers,” after Jackson’s opponents discovered Rachel was still married to her first husband when she married Jackson.

Jackson’s enemies called his wife a bigamist and his mother a “common prostitute.”

Mudslinging also came from Jackson’s supporters, who referred to Adams as a “corrupt bargainer” and an “unscrupulous aristocrat” who had misused tax dollars.

After Jackson won the election, Rachel said she “would rather be a door-keeper in the house of God than to live in that palace in Washington.”

On Dec. 22, 1828, just three months before her husband’s inauguration, she died of a heart attack.

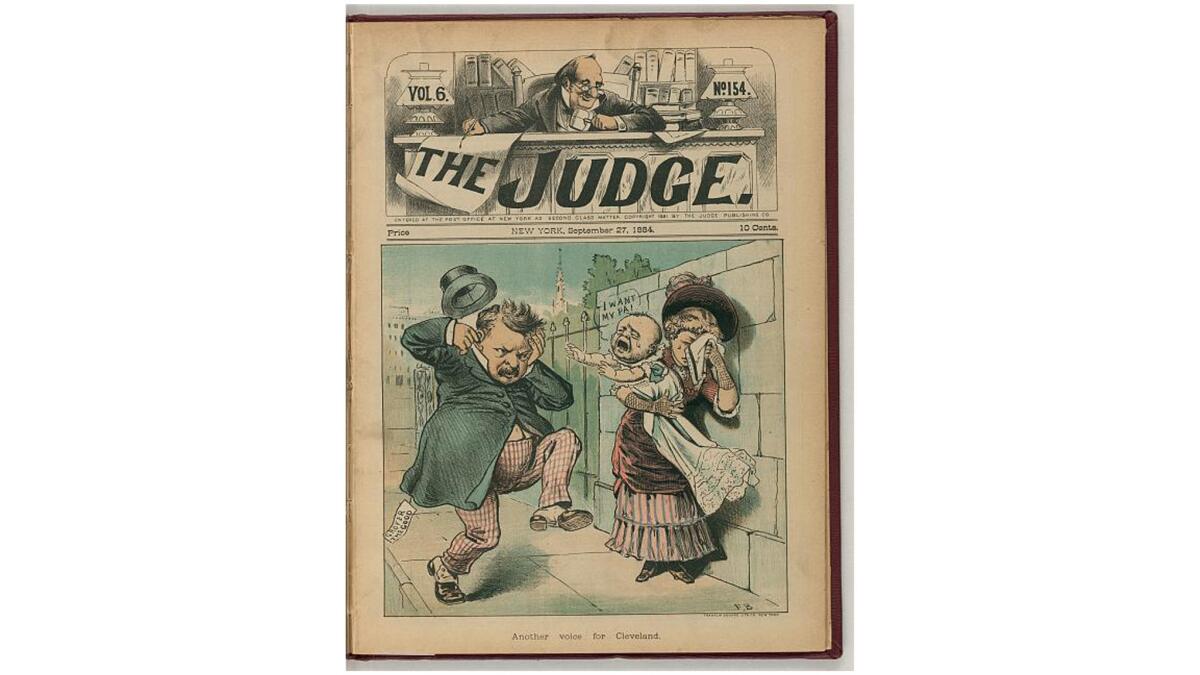

1884: ‘Ma, ma, where’s my Pa?’

In 1884, supporters of the Republican presidential candidate, James G. Blaine, created a jingle about an out-of-wedlock child his adversary, Grover Cleveland, had fathered: “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?”

Cleveland admitted to an affair with a woman named Maria Halpin 10 years earlier. The entanglement produced a son who was given the surname Cleveland. The baby was placed for adoption and Halpin was promptly sent to an asylum.

The scandal didn’t prevent Democrats from creating their own jingles. They began spreading rumors of Blaine’s crookedness with, “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, The Continental Liar from the State of Maine!”

After Cleveland won the election, Democrats had the last word with this rebuttal to their opponents’ jingle: “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa? Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha!”

1964: The ‘Daisy’ ad

Midway through the 20th century, one of the most notorious ads ever shown during a political campaign ran on Sept. 7, 1964.

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Peace Little Girl (Daisy)” campaign ad aired only once, during an NBC broadcast of “Monday Night at the Movies.”

In the ad, a little girl in a field plucks the petals off a flower. A voiceover begins a countdown while zooming in on the girl’s face. Once the countdown is complete, the video quickly cuts to a nuclear bomb detonating.

Then Johnson’s voice is heard: “These are the stakes. To make a world in which all of God’s children can live or to go into the dark. We must either love each other or we must die.”

Johnson had been vice president under John F. Kennedy, and ascended to the presidency in 1963 when Kennedy was assassinated. He ran for president against Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, whose ads were old-fashioned compared to Johnson’s.

Johnson wanted voters to focus on Goldwater’s right-wing views, and zeroed in on comments Goldwater had made about the possibility of using low-yield nuclear weapons in the Vietnam War.

Johnson’s campaign released another ad, “Merely Another Weapon,” displaying the detonation of a nuclear bomb and quoting Goldwater as saying atomic weapons were “merely another weapon.”

1968: Violence and Fear

Leading up to 1968, the number of American troops in Vietnam had risen, and opposition to the war was mounting. Johnson shocked the public by announcing he would not seek reelection.

The subsequent months seemed to bring one unimaginable shock after another. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, triggering riots in many major cities. Then Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who was running for the Democratic nomination for president, was also killed. Antiwar demonstrations grew in size and intensity, and a hyper-aggressive police response to protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago led to scenes of horrifying violence and chaos, with demonstrators chanting, “The whole world is watching!”

Vice President Hubert Humphrey became the Democratic presidential nominee. Former Vice President Richard Nixon was nominated his Republican opponent.

Nixon’s campaign focused on a “law and order” theme, and its TV commercials focused on images of a country raging out of control. His ads showcased rising crime, street violence and the unpopular war raging in Vietnam.

In Nixon’s “Failure” ad, sinister music plays as images of destruction and warfare sweep across the screen.

“How can a party that can’t unite itself unite the nation? How can a party that can’t keep order in its own backyard hope to keep order in our 50 states? … How, in the light of all this, can the American people fail to see that the United States urgently needs new leadership? By now it’s clear. The American people do see the need.”

Twitter: @alexiafedz

ALSO

'A sense of panic is rising' among Republicans over Trump, including talk of what to do if he quits

Hillary Clinton is content to let Donald Trump grab the attention while she campaigns

Obama: Trump is 'unfit to serve as president,' and Republicans should take back their endorsements

How Khizr and Ghazala Khan went from grieving parents to stars of the presidential race

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.