In need of life-saving surgery, he was promised refuge in America. Just 15 months later, he died — still waiting

- Share via

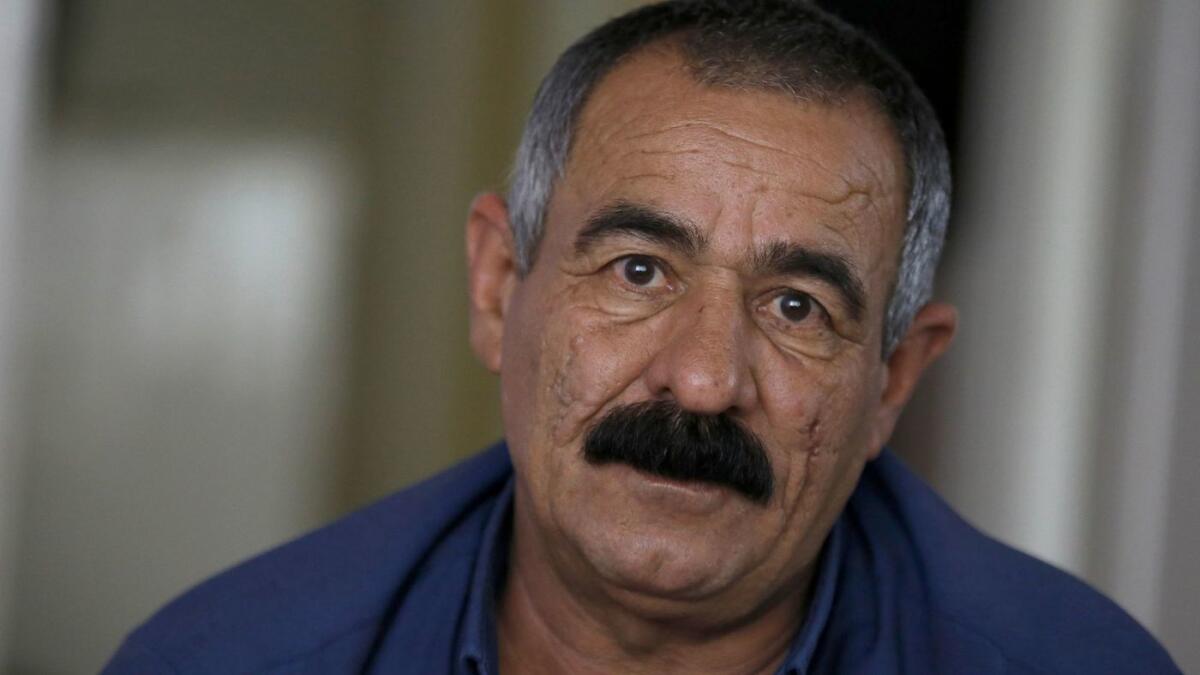

Seid Moradi was elated when he found out his family had been approved to resettle in America.

As non-Muslims who’d fled death threats in Iran, the family barely scraped by in Turkey. His sons had trouble finding work because of discrimination toward refugees. His wife picked through trash bins for food. And the family of six crammed into a friend’s apartment.

Moradi’s case had a special urgency, however. He needed life-saving surgery for a bulging blood vessel by his heart. An American doctor, he was told, could perform the operation once he arrived in the U.S.

But as President Trump signed shifting restrictions on refugee resettlement — at one point closing the country entirely to all new refugees — the family’s flights to the U.S. were canceled again and again with little explanation. Be patient, officials told the family, which over the years had passed dozens of interviews, background checks and medical visits for U.S. resettlement.

This month, more than four years after fleeing his small town of Sarpol-e Zahab near the Iraqi border and 15 months after he was told he could come to the U.S., Moradi collapsed and died on his balcony in Kayseri, Turkey. The swollen blood vessel had burst, triggering a heart attack. He was 54.

There are more than 76,000 refugees in the pipeline waiting to come to the United States, including those who still must be screened by the Department of Homeland Security, having been referred to this country by the United Nations or one of the nine refugee service centers the U.S. has designated to process refugee applicants around the world. Of that 76,000, thousands are thought to be refugees with pressing medical needs, according to refugee agencies. Those with life-threatening medical problems, such as Moradi, have historically been given priority.

This month, the U.S. announced the lowest refugee limit in its history. A maximum of 30,000 refugees will be allowed in for the fiscal year beginning Monday. Last year, the cap was set at 45,000, but only about 21,000 were admitted. Refugee resettlement groups say the U.S. government may approve only half the new limit this coming year amid increased screening procedures, a decrease in refugee interview slots abroad and the closure of dozens of resettlement offices in the U.S. — changes that have resulted in a backlog of tens of thousands of applicants.

The Trump administration says it is committed to resettling refugees but is doing it more deliberately and in smaller numbers to ensure security. In announcing the decreased refugee ceiling, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo said the country had a backlog of hundreds of thousands of asylum cases that were taking resources away from processing would-be refugees. Refugee groups contend that both programs can operate effectively, as they have in previous years.

They point to cases such as Moradi and his family as tragic examples of the nation’s retooled refugee system failing those who need it the most.

“This family is the poster child for refugee resettlement,” said Nicky Smith, who directs the International Rescue Committee office in Seattle, which had prepared for the Moradi family’s arrival. “They are a religious minority. They are an ethnic minority. They had a family member with an urgent medical condition. In most years, this would all put you on the top of the list to get to the United States.”

That’s not necessarily the case anymore, according to refugee agencies, human rights advocates and former federal government officials.

It’s not known how many people with critical health issues die while in line for admission to the U.S., though the waiting list has grown longer and will grow moreso as the government tightens how many refugees it allows in the country.

There is no requirement that any of the agencies that handle refugee applications be alerted when someone dies, and refugee groups in the U.S. typically have no direct contact with refugees until they land in the country.

“The process to get into the U.S. used to take 18 to 24 months,” said Anne Richard, the assistant secretary of State for population, refugees and migration in the Obama administration, which during its last year had pledged to bring 110,000 refugees to the U.S. “Every now and then, I am sure someone in a family may die while waiting. But it was not the norm.”

Now it feels different, Richard said.

“Many refugees have extreme circumstances that the U.S. has offered to help with, such as health conditions, and there is a concern among refugee groups that more and more could be left to die as it becomes harder to get into the country,” she said.

The International Rescue Committee only learned of Seid Moradi’s death after it was told by The Times, which profiled the family last year. A spokeswoman for the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration declined to speak about the family, saying she said could not comment on individual refugee cases.

The journey from Iran to seek a home in the U.S. was a long one for Moradi. According to interviews last year, he worked for a water and power company in his homeland before fleeing. One day, after complaining of mistreatment by his boss because of his faith, he said he was threatened with jail and interrogated by the police.

The description is similar to examples on a State Department website about the treatment of members of his religion, Yarsanism, which is a syncretic faith that traces its roots to 14th century Iran. The Iranian government considers its followers to be part of a “false cult.” About 2 million live in the country.

In August 2014, Moradi gathered his savings and boarded a bus for the more than 20-hour ride across the country’s northwestern border with hopes of starting anew. His family later joined him, and they were approved for asylum by authorities in Ankara, Turkey. They moved to Kayseri, where they lived with a family friend.

Within a year, they applied with U.N. authorities for refugee resettlement to an unspecified country. A year later they received approval to come to the U.S. after passing medical and security clearances that included interviews and submitting extensive records of travel, job, residence history and relatives names.

By June 2017, a flight to the U.S. had been booked and the Moradis sold everything they couldn’t fit into suitcases. Then, without explanation, their tickets were suddenly canceled, as were two subsequent flights, as federal court cases over the president’s travel ban loosened and tightened the flow of refugees into the U.S.

Since last October, when new refugee vetting restrictions went into place, the Moradis have heard nothing about coming to America, where they expected to live in Seattle. Their medical and security clearances to enter the country have expired. And without their father, the main refugee applicant, they will probably need to reapply.

“Right now, my mom isn’t working and my sister isn’t working,” said Sirvan Moradi, 24, a son who works temporary jobs sewing clothing. “Sometimes, my brother finds work. Once or twice a month, he finds a job in construction, then they kick him out.”

Seid Moradi’s wife, Fanoos, used to work odd jobs as a hairdresser. But since her husband’s death she’s suffered from depression and is now recovering from liver surgery. Along with three other family members, she and Sirvan squeeze into the third-floor apartment they share with a friend, where beds and furniture are few and paint chips fall from the walls. Oftentimes all five sleep in the same room.

“Since I was a kid, I’ve liked America,” Sirvan said. “My entire family did. But now Trump did this and I’m upset. My dad could have been saved if he came to America.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.