Suspicion surrounds Mississippi hanging, though suicide is suspected

- Share via

Reporting from PORT GIBSON, Miss. — They found the black man’s body hanging by a bedsheet from a locust tree.

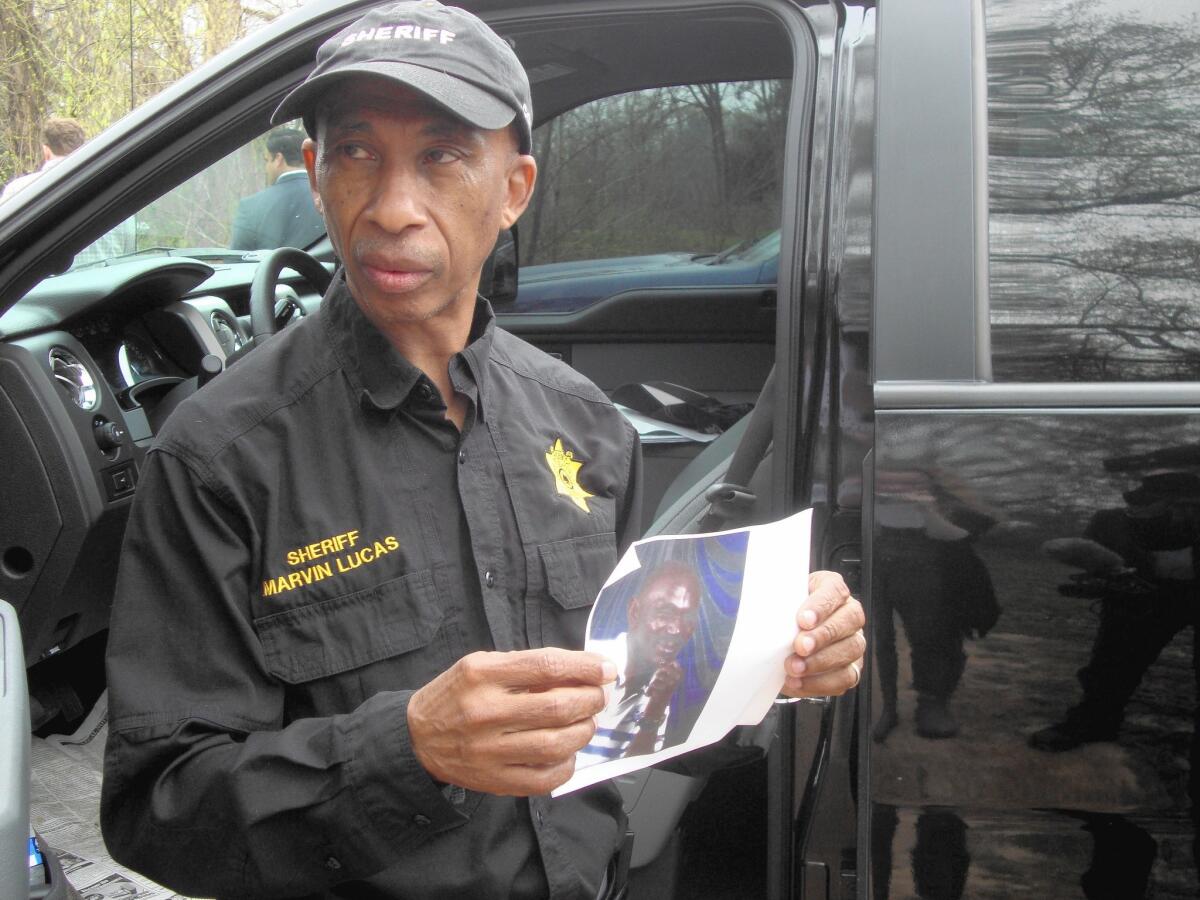

Claiborne County Sheriff Marvin Lucas called in everybody he could think of. The Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. The FBI. By late Friday, a day after the disturbing discovery, they had identified the man as Otis Byrd, a 54-year-old riverboat worker who had been missing for more than two weeks.

What they didn’t have was the answer to the question on almost everyone’s mind: Was it a lynching?

At a time when violence against African Americans — some of it at the hands of the police — has become one of the nation’s most incendiary points of civic friction, a report of a black man dangling from a tree deep in the woods of rural Mississippi was bound to attract attention.

As television crews trickled into town, local residents appeared on the sidewalks of this small rural town, home to fewer than 1,500 people, carrying signs now familiar in cities across the U.S.: “Black Lives Matter.”

“Somebody did something to him,” said Stephanie Atlas, 47, a home health aide.

Officials said Friday they had not yet determined how Boyd had died, though a federal law enforcement official said investigators were leaning toward suicide as an explanation.

FBI, state and local officials said they had 30 investigators working on the case.

The image of the body in the woods contrasted with a town of moss-draped greenery and ornate antebellum facades. Many of the building fronts survived the Civil War because Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had proclaimed the city “too beautiful to burn” — words on the sign on the entrance to town, beyond which roads cut their way through primeval forest.

Claiborne County has the third-highest percentage of African American residents of any U.S. county, an 84% majority of the population.

And unlike other parts of Mississippi, Claiborne County was not known for racial violence.

Its main claim to prominence during the civil rights era was a successful and much-publicized boycott that started in 1966 and pushed local businesses and civic leaders to hire more blacks.

When white-owned businesses tried to force protesters to repay them for hurting business, the boycott advocates appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — and won.

Today, there are few signs of racial friction. Many officials in Port Gibson and the surrounding county are black, including the sheriff, mayor, city clerk and five of six city aldermen. The town still boasts an “active and organized” black community, according to Derrick Johnson, president of the state’s NAACP.

Now, everyone wanted to know whether there had been a lynching. Some wondered whether it might have been retaliation: Byrd had served time for killing a white woman.

Across the U.S., there were 4,742 lynchings between 1882 and 1968, about 3,400 of which targeted blacks, while 1,297 involved whites — mainly allies of civil rights efforts — according to Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights advocacy group. Mississippi had the most lynchings, 581.

On Friday, Donald Alway, special agent in charge of the FBI office in Jackson, Miss., stood in front of the town courthouse with its Confederate memorial, facing a crowd of reporters and about 20 residents, all black, some of whom questioned him about the cause of death and the condition of Byrd’s body. No, he said to one questioner, Byrd had not been shot in the head.

“We’re trying to determine the cause of his death,” Alway said.

Alway said a forensics team completed its search overnight. The team examined Byrd’s home, were going through a storage unit he had rented and were interviewing his family. They were trying, he said, to gain insight into Byrd’s life, “to get the answers we all are seeking” and “the truth that everybody deserves.”

“Everybody wants answers as to who is behind this,” Alway said.

But he left Friday without offering any.

The crowd was skeptical.

“They’re just retaliating for what he did,” said Anita Smith, 54, a high school classmate of Byrd.

Byrd was convicted of killing a 55-year-old white convenience store clerk, Lucille Trim, in 1980, served his time and was released in 2006.

He returned to Port Gibson and had been working on a riverboat half the year, according to relatives who live in a cluster of brick and mobile homes outside town beyond the cotton fields, an area they call Byrdville.

Recently, Byrd rented a house across town on Old Rodney Road near an area where Trim’s relatives live known as Trim Hill. (The sheriff said investigators would be questioning Trim’s relatives.)

Byrd was last seen March 2, when an acquaintance picked him up near the Riverwalk Casino in Vicksburg, about 30 miles north, and drove him home by 11 p.m., according to Lucas. The man, whom Lucas knows, told him he didn’t talk much to Byrd, but that he seemed to be in good spirits.

Byrd usually checked in with his family daily, but after that day, he stopped calling. On March 8, the family filed a missing-person’s report and the search began the next day.

The sheriff called in state fish and wildlife officials, who found Byrd’s body hanging, fully clothed, with his boots on and a knit cap obscuring his face. Trees grow thick in surrounding woods, veiled with vines and Spanish moss, concealing the area from nearby homes.

There was no note, Lucas said. There were no other visible signs of distress on Byrd’s body. Lucas said the man’s hands and feet were not tied or bound, his mouth was not gagged.

Lucas knew what Byrd looked like — he had seen him at their church, Mt. Burner Baptist, and when the ex-convict came to check in with his parole officer at the sheriff’s office. But the body had been hanging for days, and the sheriff could not immediately identify him.

“I’m 57 years old, and that’s the first time I’ve seen anything like that,” Lucas said, vowing, “Were going to get to the bottom of it.”

Johnie Baker, 87, a white sharecropper’s son who owns the 40-acre property where Byrd was found, lives up the road and had greeted him a few times. He did not think his death was a hate crime.

“I don’t think it was repercussions for what happened in the past,” he said, referring to Byrd’s criminal record, and he didn’t think it was a lynching, either. “That would be my last conclusion — that it was race-related,” he said.

Johnson, of the local chapter of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, praised the way investigators were handling the case so far, but didn’t rule out lynching because “we still live in a time when the thought of racial hate crimes is a possibility.”

Still, there have been several other cases in recent years of black men who at first appeared to have been killed because of their race but whose deaths were later ruled suicide or murder for other reasons.

Five years ago, NAACP leaders questioned FBI and local officials in Greenwood, Miss., who ruled that the hanging of a 26-year-old black man with a history of mental illness was a suicide. Greenwood is about 130 miles north in the same Mississippi Delta county as the town where 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in 1955, fueling years of protests.

Racial animus was suspected two years ago when the body of Marco McMillian, a 33-year-old black, openly gay mayoral candidate, was found in a ditch 170 miles north of here in Clarksdale, Miss. He had been strangled, and his body was burned. A 22-year-old black man who claimed he felt threatened when McMillian came on to him was later convicted of the murder and sentenced this month to life in prison.

Many Port Gibson residents left Friday’s FBI briefing convinced that Byrd’s death was just as suspicious.

Several brought handmade signs saying, “Justice for Byrd,” “Time for Change in Mississippi” and “Black Lives Matter,” a rallying call for protesters after the shooting death of an unarmed black 18-year-old by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., last summer. The black and white signs resembled those depicted in a mural across the street commemorating Port Gibson’s landmark civil rights boycott.

Several, including Rico Jones, 38, a lumber hauler, said they were glad the FBI had arrived — but still felt ill at ease. “This is history repeating itself,” he said.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

Times staff writers Richard A. Serrano in Washington and Michael Muskal in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

ALSO:

‘Dead cops ... that’s what they want,’ says police union’s Jeff Roorda

The literary life (and death) of Susan Berman, alleged Robert Durst victim

Students find teacher Jillian Jacobson hanged in classroom: ‘RIP Mrs jacobson’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.