At least 18 states are looking into changes in the way they draw congressional and legislative districts

- Share via

Reporting from Jefferson City, Mo. — Responding to complaints about partisan gerrymandering, a significant number of states this year are considering changing the criteria used to draw congressional and state legislative districts or shifting the task from elected officials to citizen commissions.

The proposals, being advanced both as ballot initiatives and legislation, are part of a larger battle between the political parties to best position themselves for the aftermath of the 2020 Census, when more than 400 U.S. House districts and nearly 7,400 state legislative districts will be redrawn.

Since the start of this year, more than 60 bills dealing with redistricting criteria and methods have been introduced in at least 18 state legislatures, already equaling the total number of states that considered bills last year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The Ohio Legislature already has placed a redistricting measure on the state’s primary ballot in May. Citizen efforts are underway to get redistricting measures on the November ballot in a half-dozen other states, which would mark the greatest number of such initiatives in decades.

Supporters already have submitted thousands of petition signatures in Michigan and South Dakota. Petitions are currently being circulated in Missouri and Utah. Colorado has two groups working on potential ballot initiatives. And an Arkansas attorney launched an initiative effort last week.

“The basic bottom line is people want fairness, and they want balanced government,” said Chuck Parkinson, a retired congressional staffer and customs official under Republican Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Parkinson is chairman of a group pushing a South Dakota ballot measure to remove legislative redistricting from the hands of lawmakers and create a nine-member redistricting commission.

Although many redistricting proposals tout at least some bipartisan support, progressive activists and Democratic-aligned donors have helped fuel some of this year’s measures.

In South Dakota, where voters defeated a similar measure in 2016, the second attempt listed just four donors as of the start of this year — former Democratic U.S. Sen. Tim Johnson, who gave $50,000, and three unions that contributed a combined $18,500.

The top donor to Utah’s redistricting initiative through the end of last year was former Democratic gubernatorial nominee Michael Weinholtz, who had given $200,000.

The president of the Michigan redistricting initiative was a supporter of Democrat Hillary Clinton’s unsuccessful 2016 presidential campaign, and the spokesman for Missouri’s initiative is a Democratic consultant.

The Missouri measure requiring a nonpartisan demographer to draw districts has taken in more than 16,000 individual donations of $25 or less, but much of the campaign’s money has come from groups aligned with Democrats. That includes about $800,000 from unions and $250,000 from an organization founded by billionaire liberal philanthropist George Soros.

Matt Walter, president of the Republican State Leadership Committee, contends the initiatives are merely “politics wrapped in some sort of illusion of citizen-participated good government.”

“What we’re seeing here right now is an organized, orchestrated effort by the progressive left to rig the system to their advantage,” Walter said.

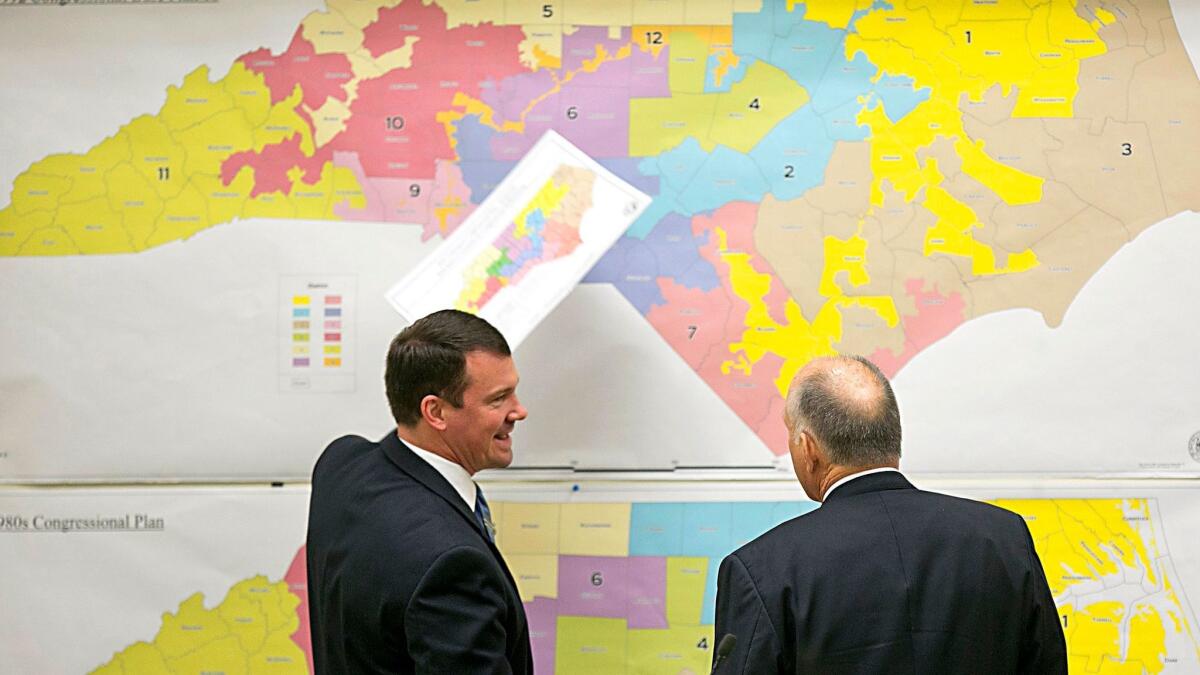

Democrats say it’s just the opposite — that Republicans rigged the system after the 2010 Census to expand the party’s grip on political power and are trying to hold on to it. They often cite North Carolina, which has been subject to multiple lawsuits over how the GOP redrew the political boundaries. Democrats have a voter registration edge over Republicans in the state, yet Republican legislators drew congressional districts in a way that gave them a 10-3 edge in U.S. House seats.

Across the country, Republicans currently control 33 governorships and about two-thirds of all legislative chambers. Democrats contend they want redistricting processes that are fair to voters, no matter which party is in power.

One of Democrats’ top targets has been Pennsylvania, where the state Supreme Court redrew congressional districts last week after ruling that the 2011 boundaries drawn by the GOP-led Legislature were unconstitutionally gerrymandered. Statistical voting models of the court’s new plan show Democrats could significantly cut into the GOP’s 13-5 seat advantage in a state where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans.

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule this year on cases alleging illegal partisan gerrymandering by Republicans in Wisconsin and by Democrats in Maryland.

An AP analysis of 2016 election data found four times as many states with Republican-skewed state House or Assembly districts than Democratic ones, based on a statistical formula cited in recent court cases. Among the two dozen most populated states that determine the vast majority of Congress, there were nearly three times as many with Republican-tilted U.S. House districts.

Democrats have since made redistricting a bigger priority. Former U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric Holder is heading the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, which is targeting or watching governors’ races, legislative elections and ballot issues in about 20 states.

Democrats want to end or diminish the legislature’s role in redistricting in several Republican-led states and shift those duties to independent or bipartisan commissions, similar to the processes in place in Arizona and California. The roles are reversed in Maryland, where Republican Gov. Larry Hogan is proposing an independent redistricting commission in a state where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans 2 to 1 and have long controlled the redistricting process.

“By and large, if a commission draws the map, it is going to be a more fair, less political, less-partisan-driven map, and that’s a good thing,” said Kelly Ward, executive director of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

But Republicans contend that even independent commissions typically are filled by people with partisan preferences.

Arizona’s Republican legislative leaders have advanced a proposed constitutional amendment to give lawmakers greater say in appointing the state’s redistricting commission.

A compromise plan placed on the ballot by Ohio’s Republican-led Legislature would continue to give lawmakers the primary responsibility of congressional redistricting but would limit partisan gerrymandering by requiring a significant percentage of “yes” votes from the minority party to approve a 10-year map.

In Indiana, the Republican-led Senate voted along party lines last month to defeat a Democratic amendment that would have created a commission to recommend congressional and legislative districts. The Senate instead passed a bill setting criteria for lawmakers to consider. That bill is now in the House.

Indiana state Sen. Greg Walker, a Republican who sponsored the pending measure, said he hopes to eventually incorporate statistical analyses of partisan advantages into the Legislature’s redistricting procedures.

“If we can demonstrate that we have made a good faith effort to not eliminate political bias 100% but certainly minimize it ... ultimately I don’t think it matters who draws the maps, because the process will fine-tune itself,” Walker said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.