Seve Ballesteros dies at 54; audacious Spaniard won five major golf titles

Seve Ballesteros, the dashing, audacious force of golfing nature who zoomed from a fishing village in northern Spain to five major titles, No. 1 in the world and a pioneer’s role in golf’s European surge of the 1980s, died early Saturday. He was 54.

Ballesteros, who enjoyed such renown for his vivid shot-making that fellow pro Nick Faldo called him “golf’s Cirque du Soleil,” died of complications from brain cancer at his home in Pedrena, the town where he was born, his family announced on his website.

Since suffering dizziness and brief unconsciousness at the Madrid airport in October 2008, Ballesteros had undergone four operations to remove a malignant brain tumor. In announcing his condition that month, he cheerfully alluded to his latest, gravest need to play escapist.

He had shone at that art during a career that often saw him stray into golf course peril and, almost as often, craft some daring shot that mocked it. The knack drew him such raves as “the most imaginative player in golf” from two-time Masters champion Ben Crenshaw, who also said of Ballesteros, “You may think he’s in trouble, but he’s never in trouble.”

Most famously, Ballesteros won the 1979 British Open at age 22 with a birdie he crafted on No. 16 despite teeing off into a temporary parking lot, where the ball landed 2 feet from a car.

From there, through two more British Open titles, two Masters victories and Ryder Cup supremacy, Ballesteros’ name often turned up beside the adjective “swashbuckling.” With his inarguable handsomeness, jet-black hair, dapper attire and unusual rations of verve and panache, he proved very popular, especially among British fans, who loved his expressive fearlessness. As the late Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote, “He went after a golf course the way a lion goes after a zebra.”

Such boldness arose from a childhood on the Bay of Biscay along Spain’s north coast, where Ballesteros would obsessively practice on the beach or sneak onto the local course to hit shots amid trees beneath full moons.

Severiano Ballesteros was born April 9, 1957, the fourth son of a noted Spanish oarsman-turned-farmer and an adoring mother, and the nephew of the golfer Ramon Sota, who finished tied for sixth at the 1965 Masters. Three older brothers would play golf professionally.

At age 8, Ballesteros received a three-iron that nearly became an appendage. In his youth he would learn every shot using that club alone, and by the time he turned professional at 17 in 1974, his unusual arsenal overrode the leanness of his amateur experience, which included only five annual local caddies’ tournaments.

In a whoosh of precocity at 19, he won the Order of Merit as the European tour’s top golfer in 1976 and said hello to the planet during a single weekend in July. That’s when he turned up at the British Open at Royal Birkdale speaking no English, staying at a bed-and-breakfast, finding a police officer for a caddie and starting off 69-69 to play the weekend paired with eventual champion Johnny Miller and finishing second alongside Jack Nicklaus.

Ballesteros won the 1979 British Open by shooting a 70 to U.S. Open champion Hale Irwin’s 78 despite zigzagging the course with a torrent of getaways from rough, sand, spectator areas and that earthen car park. By 1980, he’d become the then-youngest Masters champion at 23, the first European Masters champion and the pathfinder from a then-belittled continent that would claim 10 of the next 19 green jackets. He’d led by 10, watched his advantage shrink to two, won by four and said, “I think I must have a very big heart.”

Ballesteros won the Masters again in 1983, deflating the field by starting the final round birdie-eagle-par-birdie. Afterward he smilingly bristled at Americans who had pooh-poohed his abilities by saying, “One year I will come over here full time, to see how good I am.”

He never became a regular on the U.S. PGA Tour, trying it once but feeling lonely, winning nine PGA titles all told.

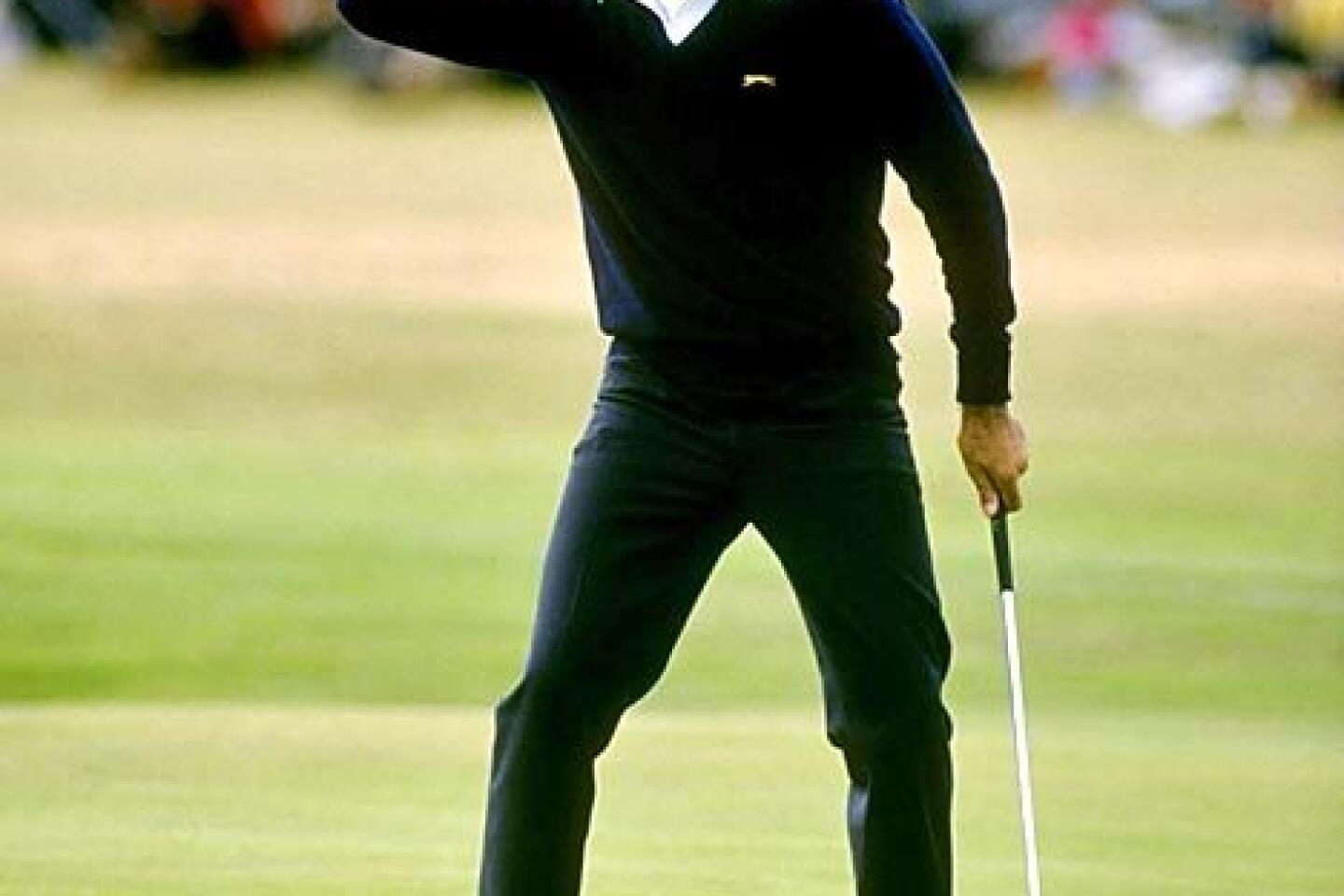

In 1984, he won the British Open again, and epically. He defeated Tom Watson at St. Andrews with a yeoman par from the rough on the Road Hole, No. 17, plus a 15-foot birdie on No. 18 and a protracted fist pump that probably rates as his most durable image.

“The most excited I have ever been on a golf course,” Ballesteros told Golf Digest in 2000.

And after his worst golf nightmare, a four-iron foray into the water on No. 15 that wrecked a two-shot lead during Nicklaus’ golden 1986 Masters, he won the 1988 British Open, again at the Royal Lytham & St. Annes, where his all-grown-up 65 included only three missed fairways and won praise from Faldo as “the greatest round of golf I’ve ever seen.”

Even at the promising golfing age of 31, Ballesteros had climbed his last major peak as a player.

But he was still to build his Ryder Cup legacy by captaining Europe to triumph in 1997 at Valderrama, Spain. It was jokingly said he had the only Formula One golf cart, seemingly managing to get to every crucial shot his players faced, offering advice, criticism and encouragement. Spanish player Ignacio Garrido said: “Seve wasn’t just a captain. He was a father for us. Our hands held the clubs, but he played the shots.”

Ballesteros’ last major top-10 finish came at the 1991 British Open (ninth). The last time he made the cut in a major was at the 1996 Masters (43rd), and he stopped playing the U.S. Open and PGA Championship, where his best finishes had been third and fifth, respectively.

As the century turned, arthritis had assailed his long-troublesome back, and his game had declined such that he continually sought diagnosis, with some opining that all the searching had blurred his natural and self-made ingenuity. In 2004, he told Observer Sport magazine of London, “I will continue to play golf for as long as I can walk, but I’ve been bad for so long now that I don’t remember how it feels to be good.”

After turning 50, Ballesteros played one senior event but stopped there. He retired after the 2007 British Open, where Tiger Woods called him “a genius” and “probably the most creative player who’s ever played the game.”

Childhood inspiration Gary Player called him “the Arnold Palmer, charisma-wise, of Europe.”

Colin Montgomerie said, “The club just looked right in his hands, always.”

Faldo went for “Cirque du Soleil,” citing the “passion, artistry, skill, drama.”

Upon learning of Ballesteros’ deteriorating condition, and only hours before his death, Spanish golfers Jose Maria Olazabal and Miguel Angel Jimenez — good friends of his — were in tears as they came off the El Prat golf course during second-round play at the Spanish Open on Friday. Olazabal and Ballesteros combined to form one of the greatest Ryder Cup pairs in history.

After he retired from playing, Ballesteros concentrated on his various business ventures, including golf course design. In his last year, his few appearances or public statements were usually in connection with his Seve Ballesteros Foundation to fight cancer.

In 2007, a girlfriend died in a car accident. In addition to his brothers, survivors include two sons and a daughter from his marriage to his former wife, Carmen Botin. The elder son, Baldomero, named for his paternal grandfather, at age 16 caddied for Ballesteros during his last appearance at a British Open (Hoylake, 2006), where he missed the cut but played creditably (74-77) and exposed his son to the adoration British fans had long held for “Seve.”

The Associated Press was used in compiling this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.