L. Bruce Laingen, top U.S. diplomat held in Iran hostage crisis, dies at 96

- Share via

L. Bruce Laingen, the top American diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran when it was overrun by Iranian protesters in 1979 and one of 52 Americans held hostage for more than a year, has died. He was 96.

Laingen died Monday of complications from Parkinson’s disease at an assisted-living facility in Bethesda, Md., his son Chip Laingen said.

Iran was in chaos in 1979, roiled by the departure of the shah of Iran that January and the return a month later of the revolution’s leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, a longtime religious leader in exile. The U.S. had supported the shah’s regime and incurred the wrath of Iranian revolutionaries before and after the shah was overthrown.

When U.S. Ambassador William Sullivan stepped down in early 1979, the U.S. sought a short-term leader for its Tehran embassy as the U.S. considered its diplomatic presence in the country, Laingen recalled for a 1992 oral history for the Assn. for Diplomatic Studies and Training. He said he accepted the appointment as chargé d’affaires to Iran with the understanding it would be for a period of four to six weeks.

Despite his wife’s reservations, Laingen said, he went to Tehran that June with a feeling of excitement. “That was where the action was,” he said.

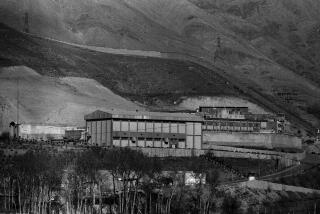

Tehran had changed in the quarter-century since he had been stationed there early in his diplomatic career. “I will never forget the impression of traveling into the city from the airport that evening ... in an armored-plated limousine with escort cars both fore and aft. Each of them were loaded with security types who had no hesitation when it was necessary to clear traffic to jump out of their cars and wave their pistols and Uzis,” he said.

On Nov. 4, 1979, protesters took over the American Embassy. For 444 days, the plight of the American hostages was a daily news story — and a never-ending political drag for President Carter as he campaigned for reelection in 1980, a bid he ultimately lost to Ronald Reagan.

Chip Laingen said his father was held separately at the Foreign Ministry for most of that period and was “treated fairly well.” His father struggled with feeling like he was the “captain of the ship” and not being with the rest of the hostages, his son said.

“It was very, very mentally wearing on him that he couldn’t be with his colleagues, the people he was helping,” Chip Laingen said Wednesday. “That was really tough on him.”

On Inauguration Day, Jan. 20, 1981, the hostages were released — a rebuke to Carter as well as recognition of a new American leader, President Reagan, who had promised a hard line against Iran.

Recalling in the oral history his feelings upon returning to the U.S. and the reception he received, L. Bruce Laingen said: “I can only remember the joy of it, the relief of it, the incredible embrace of affection we had from every American.”

Laingen was born Aug. 6, 1922, on a farm in southern Minnesota near the towns of Butterfield and Odin. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he graduated in 1947 from St. Olaf College in Minnesota and earned a master’s degree in international relations in 1949 from the University of Minnesota.

Laingen was a member of the U.S. Foreign Service from 1950 to 1987, serving in Germany, Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan before being named U.S. ambassador to Malta in 1977.

After his release in 1981, Laingen served as vice president of the National Defense University. He followed his retirement from the Foreign Service with numerous government- and education-related activities, including 15 years as president of the American Academy of Diplomacy.

Survivors include his wife, Penelope, and three sons.

Looking back on the ordeal 25 years later, Laingen said in a 2004 interview that it didn’t make sense for the U.S. to have little dialogue with Iran given the American stake in the Middle East.

“We need to understand Iran, and Iran needs to seek to understand us,” he said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.