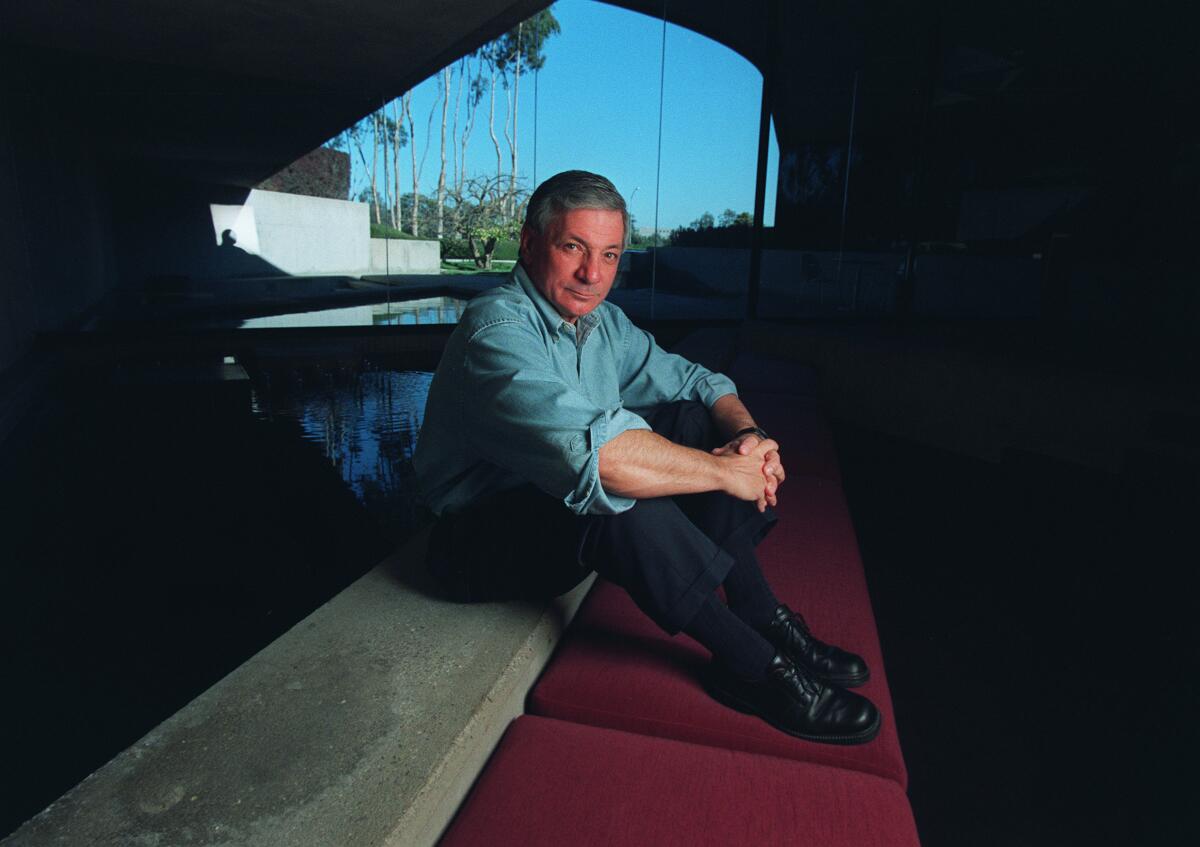

Jerry Hirshberg, who opened Nissan’s first design center outside Japan, dies

- Share via

Jerry Hirshberg put his stamp on a fleet of cars, from the 1971 Buick “Boattail” Riviera to the 1999 revival of Nissan’s sporty Z car. But the longtime Del Mar resident also designed golf clubs, laptop computers, children’s furniture, a yacht — and a zestful, ever-creative life.

The founding director of Nissan Design International in La Jolla, Hirshberg died Sunday at the age of 80. The cause of death was glioblastoma, a brain cancer that had been diagnosed a year ago.

A restless innovator who idolized Leonardo da Vinci, Hirshberg was a musician, painter and writer who in 1980 opened Nissan’s first design center outside Japan. Equipped with the standard wood shop, metal shop and modeling spaces, NDI had aspects reminiscent of an Ivy League campus and a Buddhist temple.

Designers browsed NDI’s library, its shelves stocked with everything from “The Oxford Book of American Verse” to current issues of American Demographics, Japanese Architect and Wilson Quarterly. Outside was a lawn the size of a football field — the better to view automobiles from every angle — and a Japanese rock garden with a cheeky American touch: 10 bowling pins that designers routinely rearranged.

While Hirshberg’s team worked long hours, the boss also led them on field trips to the movies, catching mid-week matinees of “Silence of the Lambs,” “Blade Runner” and “Total Recall.”

“All of this,” Hirshberg said during a “Jurassic Park” screening, “is management of the creative process.”

Gerald P. Hirshberg was born on July 7, 1939, in University Heights, Ohio. A musical prodigy, at 6 years old he studied composition and conducting at the Cleveland Institute of Music. He played clarinet for the Cleveland Youth Symphony and as a teen formed a rock ’n’ roll band, Jerry Paul & the Plebes. Opening for Frankie Avalon, Fabian and other acts, they recorded several singles, including “I Want My Ring Back” and “Sparkling Blue.”

Also a skilled painter, Hirshberg graduated with honors from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1963. He accepted a fellowship to continue his art studies in Europe, even as his ambitions were turning in another direction.

Hirshberg often recalled a scene from his boyhood, when he asked an uncle about the family’s Philco radio. Who dreamed up this lovely, yet functional, item?

“An industrial designer,” he was told.

“Something about the unlikely combination of those two words — ‘industrial’ connoted smokestacks and machinery and ‘design’ connoted art and communication — fired my imagination,” he told a reporter in 2000. “There was something to me about the tension between making what works beautiful and making what’s beautiful work, something about the push and pull.”

Home from Europe, he was hired by General Motors in 1964 and teamed with another hotshot designer, John DeLorean. They crafted a series of snazzy cars: the Buick Le Sabre and Skyhawk, as well as the Pontiac GTO, Firebird, Sunbird and Grand Prix. Eventually, though, Hirshberg bridled at what he saw as GM’s car-by-committee environment. When Nissan came courting in 1979, Hirshberg listened.

NDI represented a union between freewheeling California and buttoned-down Japan. The marriage was often strained. By 1997, Hirshberg had logged more than 80 flights to Tokyo, meeting with Nissan’s brass, often engaged in tense arguments on behalf of his team’s styling. To help make his case and better understand his colleagues, Hirshberg spent years studying the Japanese language and culture.

“It’s very intimidating,” he said in a 1992 interview. “It increases your appreciation of the risk people take all the time when they speak our language.”

The 1990s were a challenging decade for Nissan, which lost $5.7 billion in 1999 alone. While NDI won critical acclaim for its XTerra SUV, Frontier truck and other models, some critics argued that the designs coming out of California weren’t bold enough.

Hirshberg himself noted that his Japanese colleagues viewed some of his designs as oaji, a Japanese term for bland.

“A lot of times when we send something that is clean and austere,” he said in a 1986 interview, “they react, ‘Oh, you’ve created oaji.’”

Nonetheless, Hirshberg and NDI won more battles than they lost. At one point, the La Jolla facility was responsible for three-quarters of all Nissans on the road.

Retiring from NDI in 2000, Hirshberg devoted more time to music and painting. A former member of the San Diego Port District’s arts advisory board, his designs were the subject of a 2001 San Diego Museum of Art exhibit. In 2009, New York’s Danese/Corey gallery hosted a show of his paintings.

A popular speaker, he often took his cues from his 1999 book, “The Creative Priority: Driving Innovative Business in the Real World.”

He served on numerous boards and commissions, including the National Endowment for the Arts’ design arts panel and the Mayor’s Growth Management Task Force for San Diego.

Hirshberg is survived by his wife of 56 years, Linda; two children, Glen and Eric; a brother, Bert; and four grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.