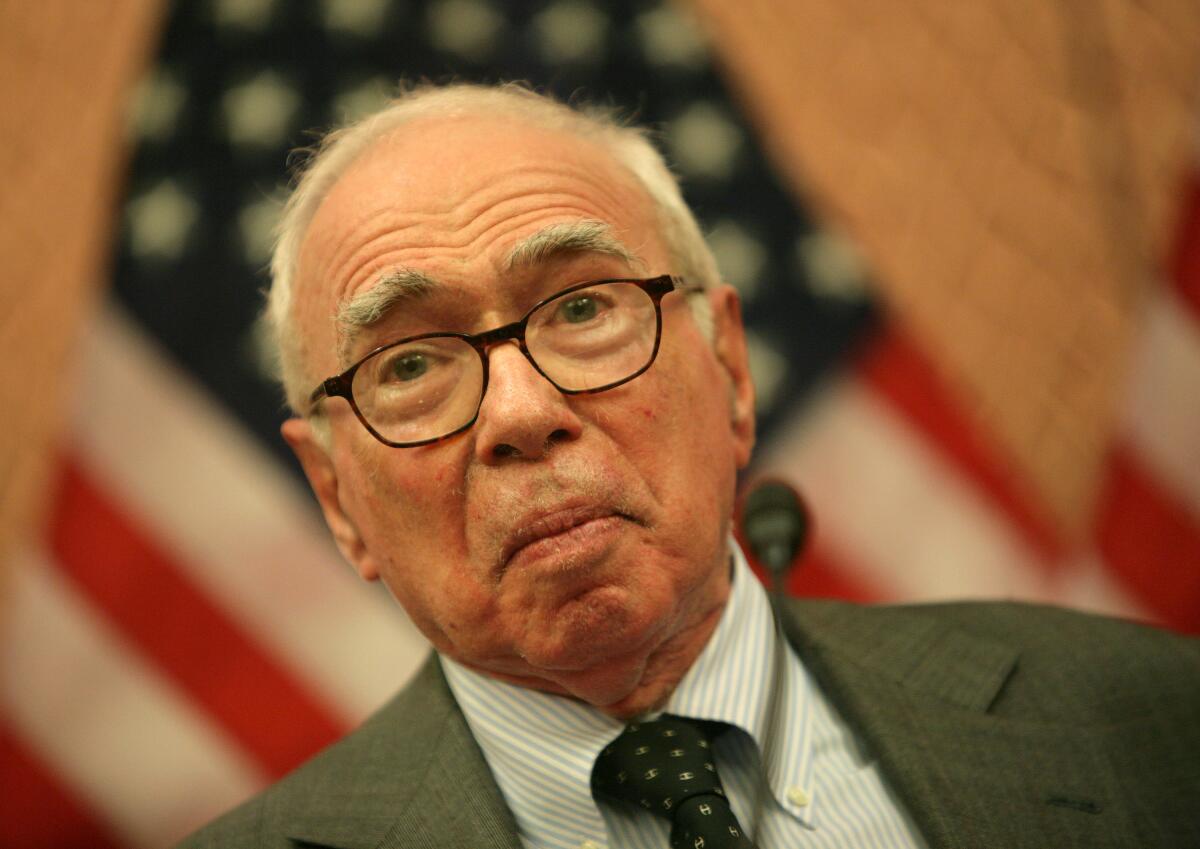

Felix Rohatyn, banker who helped rescue New York, dies at 91

- Share via

Felix Rohatyn, a pioneer of Wall Street’s lucrative corporate-acquisition business who steered New York City from bankruptcy in the 1970s and remained an unelected guardian of its finances for almost two decades, has died. He was 91.

Rohatyn’s death at his home in Manhattan on Saturday was reported by the New York Times, citing his son Nicolas. No cause of death was given.

As managing director of Lazard Freres & Co., now Lazard Ltd., Rohatyn earned the not entirely flattering nickname “Felix the Fixer” for his deal-making during the mergers-and-acquisitions boom that began in the 1960s. He exerted similar influence in government finance starting in the 1970s.

“Felix may have come as close as any man -- certainly any Jewish man -- in the past century to replicating, in his own, less ostentatious way, the extraordinary financial, political and social influence that J.P. Morgan had wielded in the previous one,” William Cohan wrote in his 2007 book, “The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Freres & Co.”

Rohatyn landed his most public post in 1975, when New York City’s finances reached a crisis point.

The city had accumulated short-term debt of about $6 billion, was running budget deficits in excess of $1.5 billion and found itself effectively locked out of credit markets where it could sell new bonds and notes. New York Gov. Hugh Carey and state lawmakers created the Municipal Assistance Corp., empowered it to issue bonds on the city’s behalf and gave it control over the city’s sales-tax revenue to repay lenders.

Rohatyn, who advised Carey during negotiations over the panel’s creation, became chairman of the nine-member board in September 1975. Nine months later, Carey also named him to the state’s Emergency Financial Control Board, increasing his power over the city’s budget.

The panels guided the city back to fiscal health. The threat of bankruptcy receded in 1978 when the federal government approved $1.65 billion in loan guarantees for New York. Carey’s successor as governor, Mario Cuomo, later said of Rohatyn’s role: “It would be difficult to exaggerate it. He literally saved the city from bankruptcy.”

As chairman of the Municipal Assistance Corp. through 1993, Rohatyn retained extraordinary power to decide how to spend the city’s surplus revenue. In all, he amassed and distributed about $3.5 billion, favoring causes close to his heart such as education and mass transit, the New York Times reported in 1993. In his exercise of public power as a private citizen, Rohatyn resembled his hero, Jean Monnet, the French economist who made European economic and political union his lifelong mission, without ever holding public office.

Not everybody celebrated Rohatyn’s broad influence. His uneasy relationship with Ed Koch, New York’s mayor from 1978 through 1989, flared into acrimony when Rohatyn, shortly after Koch left office, criticized him for the generosity of city labor contracts.

Firing back, Koch accused Rohatyn of stockpiling those billions in city tax revenue by intentionally underestimating interest accruing on money held by the corporation.

Early Years

Felix George Rohatyn was born May 29, 1928, in Vienna, an only child. His mother, the former Edith Knoll, a pianist, came from a family of wealthy Viennese merchants. His father, Alexander, worked in breweries owned by his own father, who ran a bank.

With anti-Semitism on the rise in Europe in the 1930s, Rohatyn’s parents moved their family to Romania, then to France. After they divorced, Rohatyn, at 8, was sent to a French-speaking boarding school in Switzerland. By the time he rejoined his mother in Paris, she had a new husband, Henry Plessner, whose precious-metals company did business with Lazard Freres et Cie.

With German troops approaching Paris, Rohatyn and his mother fled south to Biarritz; Plessner, a Polish citizen, escaped from an internment camp and met them there. The family spent a year in Cannes before securing, from the Brazilian government, the visas they needed to leave France.

Decades later, Rohatyn would learn from the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation that Luiz Martins de Souza Dantas, Brazil’s wartime ambassador to France, had provided the visas as part of his secret effort to save Jews.

After yet more stops -- in Algeria, Morocco, Portugal, Brazil -- the family reached New York City in June 1942. The two-year odyssey, Cohan wrote, made Rohatyn “preternaturally pessimistic about the outcome of events, extremely conservative financially and far less prone to excessive ostentation than most of his extremely wealthy investment banking peers.”

Meyer’s Protege

In New York, Rohatyn attended the McBurney School and graduated in just two years while mastering English. He enrolled at Middlebury College in Vermont, intending to pursue a career in physics or engineering. Upon his graduation in 1949, he got a summer job at Lazard Freres in New York through his stepfather. He worked his way up, interrupted by a two-year stint in the U.S. Army, and became a partner in 1961.

He was a protege of managing partner Andre Meyer, an innovator in the growing field of mergers and acquisitions. Rohatyn helped Meyer buy, improve and then sell Avis Inc. to International Telephone & Telegraph Corp. for a hefty profit. That deal “led directly to the creation of the M&A advisory business and Lazard’s domination of it,” Cohan wrote.

Much of Lazard’s early acquisitions work was in support of ITT’s buying spree under then-Chairman Harold Geneen, the executive widely credited with creating the multinational conglomerate.

ITT’s 1968 announcement that it would buy Hartford Fire Insurance Co. for $1.5 billion led to 13 years of litigation and investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Justice Department and the Internal Revenue Service into the sale of stock as part of the transaction.

Grand Jury

According to Cohan’s book, federal prosecutors convened a grand jury to consider whether Rohatyn -- an ITT director as well as its point person at Lazard -- had committed any crime in the case. No charges were filed, and Rohatyn told Cohan that he had “absolutely no recollection” of a criminal investigation.

The case also raised questions about whether President Nixon’s administration had undercut an antitrust investigation of ITT in exchange for a $400,000 corporate contribution to the 1972 Republican National Convention.

Rohatyn had met with then-Deputy Atty. Gen. Richard Kleindienst to try to head off the antitrust probe. When the Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings to weigh whether the case should affect Kleindienst’s nomination as attorney general, Rohatyn was by his side.

Kleindienst’s Testimony

Kleindienst testified that the Nixon White House had stayed out of the antitrust matter. He was confirmed and served a year as attorney general, then pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of perjury when records established that the Nixon administration -- and even Nixon personally -- had in fact intervened on ITT’s behalf.

The affair tarnished Rohatyn’s name. The Washington Post’s Nicholas von Hoffman gave him the pejorative label “Felix the Fixer.”

Bad publicity didn’t stop his rise, though. In 1970, the New York Stock Exchange named him to head a committee charged with stanching a run of brokerage failures caused by back offices being overwhelmed by surging trading volume. The “Crisis Committee” pulled Wall Street out of trouble. Carey’s call to help save New York City came in 1975.

Rohatyn earned no salary for his city service and continued to steer deals at Lazard, including R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.’s $4.9-billion acquisition of Nabisco Inc. in 1985, the $15.7-billion merger of Time Inc. and Warner Bros. in 1990, and Viacom Inc.’s takeover of Paramount Communications in 1994 for $9.6 billion.

Important Voice

He also remained an important voice on Wall Street, even if his advice wasn’t always followed. In a 1992 article, he warned that derivatives -- the complex financial instruments that would play a central role in the global credit crisis of 2007 -- were “financial hydrogen bombs” created by “26-year-olds with computers.” His 2009 book urged the creation of a National Infrastructure Bank to direct federal funds to roads, bridges and schools in greatest need of money.

Long seen as a candidate to lead Lazard, Rohatyn declined the chance in the late 1970s. Toward the end of his long tenure he battled publicly with Steven Rattner, a one-time protege who seemed to be on the path to chairman. Rattner left Lazard in 2000 to start a private-equity firm.

Republican Opposition

Rohatyn’s financial support of the Democratic Party was almost rewarded in 1996 when President Clinton floated his name as vice chairman of the Federal Reserve. In the face of opposition by Republican senators, Rohatyn withdrew from consideration. Clinton then named Rohatyn as U.S. ambassador to France, a post he held from 1997 through 2000.

In April 2001, he founded Rohatyn Associates LLC in New York to provide financial advice to corporations. In 2006, he joined Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. as an adviser to Chief Executive Richard Fuld, an affiliation that ended when the firm declared bankruptcy two years later.

Among other roles, Rohatyn was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, vice chairman of Carnegie Hall and a commander in the French Legion of Honor. In 2002, Middlebury College put his name on its Center for International Affairs.

Rohatyn had three sons -- Pierre, Nicolas and Michael -- with his first wife, Jeannette Streit, who died in 2012. The marriage ended in divorce in 1979. That year he married the former Elizabeth Fly Vagliano, who served as president of the New York Public Library and founded a nonprofit group, Teaching Matters Inc., that trains public-school teachers. She died in October 2016.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.