Grace Montañez Davis, former L.A. deputy mayor and Eastside political activist, dies at 93

- Share via

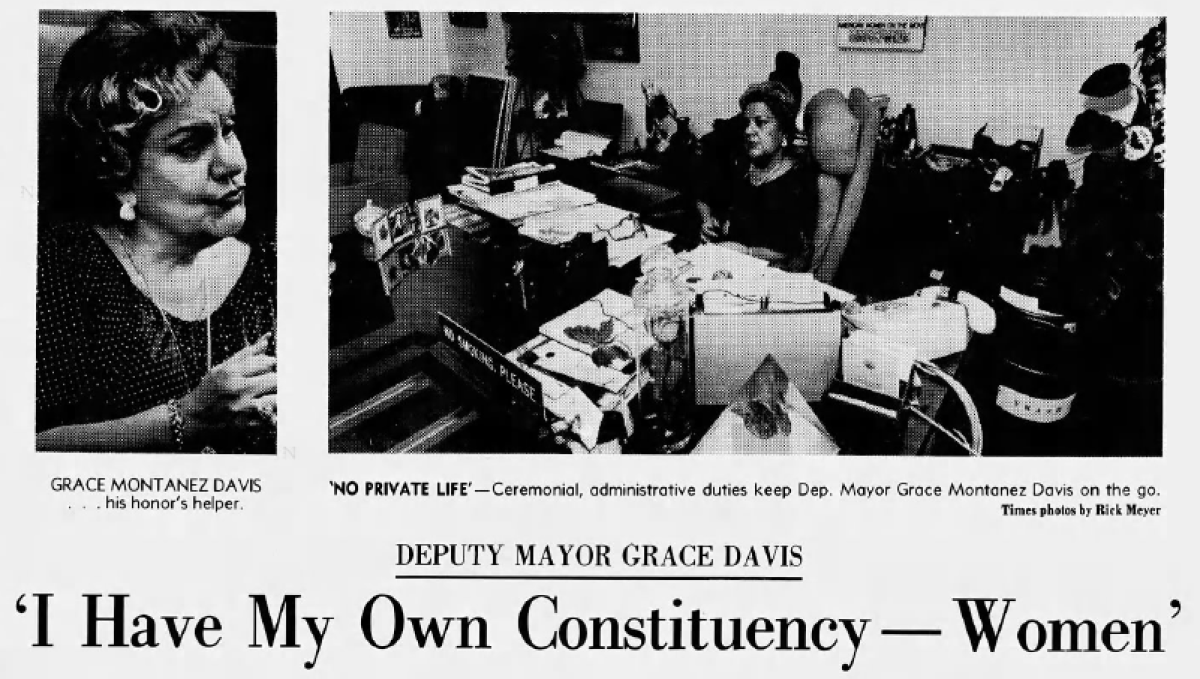

Grace Montañez Davis was the first Mexican American woman to serve as Los Angeles’ deputy mayor, and it was no easy feat.

People assumed she was the mayor’s social secretary; she’d often get phone calls and bills addressed to Tom Bradley’s then-campaign aide, Gray Davis, the state’s future governor. The first time she gathered the city’s 38 department heads, 36 of them men, her body shook with nerves.

But in the 15-plus years she served in city government, Montañez learned the ins-and-outs of the job like no other and became known for her attention to detail.

“Before she moves, she knows the facts and figures,” Tom Houston, former chief of staff for Bradley, told The Times in 1985. “She takes her time. She is appropriately cautious. And she generally knows the outcome.”

It was the most prominent position in her career. But behind the scenes, Montañez was a constant aide in the rise of Mexican American political power for decades.

She was there in 1949 to register voters who helped make Ed Roybal the first Latino council member in Los Angeles since the 19th century. Montañez was present at the Chicano Moratorium, shoved into a van and sped off by younger activists when the anti-Vietnam War rally in East Los Angeles turned violent. She marched and picketed with farmworkers during the Delano grape strike. And as more Latinos from the Eastside began entering public office, Montañez offered pointers and her perspective as a pioneer.

“She transcended these different movements,” said Virginia Espino, a lecturer for UCLA’s Chicana/o and Central American Studies program who interviewed Montañez in 2008 for a university oral history project. “Typically, when I try to interview Latina women of her generation, they tend to be shy about their accomplishments. But Grace was someone who knew the value of her life history and gladly told it.”

Montañez, who was the highest ranking woman and Latina during Bradley’s administration, died Saturday of heart failure at a hospital in Upland, said her daughter Deirdra Christian. She was 93.

“I remember many times she was the only woman in a large group of men,” recalled Christian.

Montañez was appointed as the mayor’s right-hand woman in August 1975, focusing her work on grants, housing and community development. Within months, Montañez took over Bradley’s duties while he was absent on a 12-day trip. Her approach at impacting the city was aimed less toward governmental bodies and more toward groups and people.

“I usually like to be in touch with the people who are going to be involved and then go to him [Bradley] and say, ‘I talked to this organization and this group of people and this is what they’re saying,’” she said. “‘They’re wondering if you would like to support this issue.’”

It’s a quality praised by those who worked with her. Bradley said that Montañez “represents a unique blend of tradition and progress” and called her “a symbol of the city’s continued commitment to incorporate all residents into its rich and diverse city life.”

Grace Montañez Davis was born Nov. 24, 1926, in Lincoln Heights. Her father, Alfredo, was a soap factory worker and her mother, Belen, a homemaker. Both were Mexican immigrants. She was the second youngest and only girl of four children, which pushed her to work harder “because she felt she needed to prove herself to her brothers,” said Christian.

Her parents enrolled her in Catholic school in seventh grade so she wouldn’t have to walk alone through the neighborhood’s business section. After high school she attended Immaculate Heart College, where she earned a bachelor’s in chemistry in 1949 and studied microbiology in graduate school at UCLA.

She was keenly aware of how rare it was for a Latina to be pursing higher education in the early 1950s.

“When I was at UCLA I once went through all the students’ cards to see if there were other people with Spanish surnames,” she once said. “There were five in the graduate school, and four of them were from Mexico or Central or South America. I was the only one [Mexican American] in graduate school at that time.” She was the only one of her siblings to pursue higher education.

It was during a function at UCLA where she met Raymond Davis, a high school history and journalism teacher. They married in Santa Monica in 1953 and divorced in 1968. They had three children. Davis died in 2011.

College also introduced her to activism, which led her to join the Community Services Organization, the group that helped to elect Roybal. Montañez not only registered new voters, but also taught citizenship classes in Spanish; one of her first graduating students was her father.

As to how Monta˜nez pivoted from science to politics, Christian said, “My mom had a really giving heart and was really concerned with people who were less fortunate, with Hispanics and people were mistreated. That’s what pointed her in that direction: She wanted to speak up for people who didn’t have a voice.”

Montañez went on to work for Roybal and helped with Rep. George Brown’s campaigns before joining the Economic and Youth Opportunities Agency in 1964, a program aimed at encouraging employment among youth. After a stint at the U.S. Department of Labor, she joined Bradley’s staff in 1973 and was promoted to deputy mayor in 1975, leaving in 1990.

Montañez’s ease in talking to different levels of el movimiento earned her respect from anyone who ever worked with her, said former Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina, who was a 20-something activist in East Los Angeles when she first met the deputy mayor. “We could’ve been so easily dismissed at the time by someone in her power, but instead, she embraced us.”

Throughout her career, Montañez was also a member of the Federal Advisory Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, National Advisory Committee on Social Security and the board of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund. Even in her later years, Montañez kept a busy social calendar and never stopped trying to advocate for Latinas.

Espino remembered how Montañez called her former bosses at UCLA when the lecturer left an oral history post “to ask if they were going to replace me with someone else to interview Chicano pioneers.”

Anton Calleia, who worked alongside Montañez for 15 years as Bradley’s chief executive officer, said she was active in her community her whole life and that human rights were at the core of her ideology.

“People like her don’t come around very often,” he said. “We were lucky to have her and I think the city is better because she was so involved, because she served so well. I genuinely believe that.”

Montañez is survived by three children, Deirdra Christian, Alison Hoverston-Davis and Alfred Davis; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.