Eli Broad, billionaire who poured wealth into reshaping L.A., dies at 87

- Share via

Eli Broad made his billions building homes, and then he used that wealth — and the considerable collection of world-class modern art he assembled with his wife — to shape the city around him.

Dogged, determined and often unyielding, he helped push and prod majestic institutions such as Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Museum of Contemporary Art into existence, and then, that done, he created his own namesake museum in the heart of Los Angeles.

With a fortune estimated by Forbes at $6.9 billion, the New York native who made California his home more than 50 years ago flourished in the home construction and insurance industries before directing his attention and fortune toward an array of ambitious civic projects, often setting the agenda for what was to come in L.A.

Active and still looking ahead until late in life, Broad died Friday afternoon at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Suzi Emmerling, a spokesperson for the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, said in a statement. He was 87. A cause of death was not given.

“We join the city of Los Angeles in mourning the loss of Eli Broad. The city and the nation have lost an icon,” Los Angeles Times Executive Chairman Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong and his wife, Michele, said in a statement.

“Eli’s life story is an inspiration and a testament to the possibilities America holds,” they said. “The Broads’ support and leadership of the cultural, educational and medical institutions that sustain us have been transformative. Our thoughts are with Edye and their family and we’re forever grateful to her and Eli.”

Photos: Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector, builder, created part of the Los Angeles landscape

Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector and builder, has died at 87.

Civic transformation was “his driving force,” Barry Munitz, a longtime Broad associate and former chancellor of the California State University, told The Times in 2004.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Broad spent millions to endow medical and scientific research programs, including stem cell research centers at UCLA, USC, UC San Francisco and Harvard. He was also a deep-pocketed booster of public education reform who funded charter schools, a training academy for school district executives and, for a dozen years, the annual $1-million Broad Prize for high-achieving urban school districts.

But he left his most visible legacy as a cultural philanthropist and broker, whose money and world-class modern art collection made him a powerful and often controversial force on the local arts scene.

In the late 1970s, he became the founding chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and he bailed it out of a financial scandal three decades later with a $30-million grant.

In the 1990s, when the effort to build Disney Hall was falling apart, he took charge of a $135-million fundraising campaign to complete construction in 2003.

That year, he also pledged $50 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to build the contemporary art wing that bears his name.

Calling himself a “venture philanthropist,” he expected his benefaction to bring more than a pat on the back and naming rights. He regarded his donations as investments, the success of which he would judge by their returns, whether in the form of scientific breakthroughs, improved test scores or higher museum attendance.

“I am a builder,” the tall, white-haired Broad once told The Times. “I don’t like to preside over the status quo and simply write checks.”

His demands made some potential recipients think twice about accepting money from Broad. “Too many strings,” said the leader of a major Los Angeles nonprofit, who asked not to be named. Others put it less politely. “Eli is a control freak,” Disney Hall architect Frank Gehry said of his former client in a 2011 segment of CBS’ “60 Minutes.”

Broad was known not only for aggressive involvement in his philanthropic projects but also for a tendency to withdraw his support when developments failed to go his way. These traits were well known in L.A.’s art world, in which he was an unavoidable force.

“The truth is that Eli is L.A.’s most prominent cultural philanthropist, and if you run a museum in this city you have a relationship with him one way or another,” Ann Philbin, director of the Hammer Museum, where Broad once sat on the board, said in a 2010 Vanity Fair article.

Broad’s relationships with the institutions he enriched were often vexing.

LACMA, MOCA, the Hammer — museums had a complicated relationship with Eli Broad. Which partly explains why he ultimately built his own.

In 2010, as a dominant member of the MOCA board, he steered the museum toward the controversial choice of Jeffrey Deitch, a New York gallery owner from whom he had purchased art, to be its new director. In 2012 he forced the resignation of the museum’s longtime chief curator, Paul Schimmel, who had clashed with Deitch over shows involving celebrity artists such as Dennis Hopper that seemed to pander to popular tastes. Several board members resigned in protest, including Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger and Catherine Opie.

In 2013, with MOCA struggling financially, Broad tried to broker a merger between the museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, a match that made little sense to many in the museum world. The proposal died amid sharp questioning by critics, including the New York Times’ Roberta Smith, who wrote: “The combination of the domineering Mr. Broad and unusually passive trustees has forced to its knees one of the greatest American museums of the postwar era.”

At LACMA, Broad insisted that the much-needed modern art wing be called the Broad Contemporary Art Museum and personally recruited architect Renzo Piano to design it and a board to govern it. LACMA agreed to his terms without a solid pledge from the multibillionaire to donate works from the 2,000-piece contemporary art collection he had built with his wife, Edythe.

Just before the 80,000-square-foot building’s formal unveiling in 2008, Broad stunned much of the museum world by announcing that he would not be giving LACMA his treasure trove of Warhols, Rauschenbergs and Lichtensteins. Instead, he said he would lend works to the museum from the private art foundation he founded in 1984, an arrangement that he believed would ensure the art he and his wife had amassed over decades would be seen and not stored away.

His decision brought pointed headlines, such as the one accompanying a New York Times story: “To Have and Give Not.” Time magazine’s Richard Lacayo was most blunt, writing on his blog, “LACMA got screwed.”

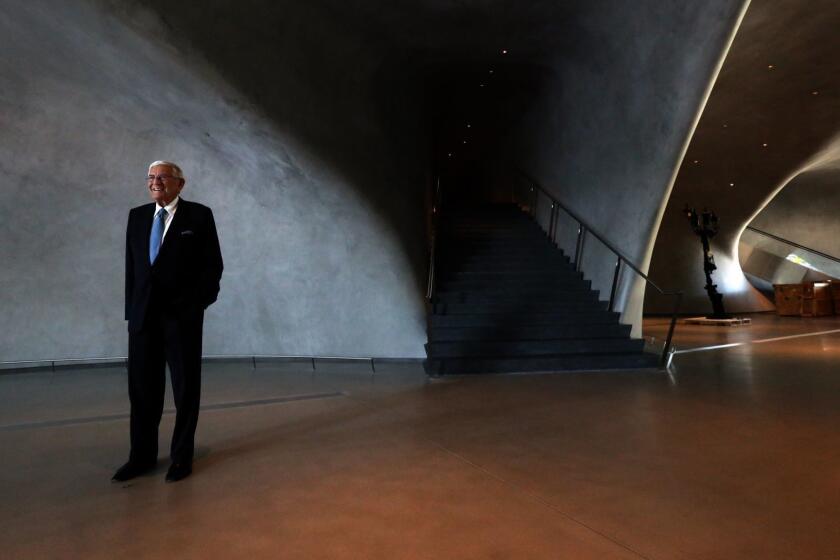

Although Broad had said over the years that he would not go the way of Armand Hammer and Norton Simon, he ultimately did decide to build his own museum. He settled on a prime downtown lot adjacent to MOCA and Disney Hall for the Broad, the eponymous museum and art lending library that opened in September 2015, part of his vision to cement Grand Avenue as the cultural heart of L.A.

“We believe we have reinvented the American art museum,” he wrote in a 2019 L.A. Times essay on Los Angeles’ cultural evolution.

Broad was a major architecture patron, who over the years supported projects by many of the world’s top architects, including Zaha Hadid — who designed the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, Broad’s alma mater — Cesar Pelli and Richard Meier.

Closer to home, he and his wife made major gifts to UCLA for a fine arts complex and to Caltech for a biological sciences center. He also supplied a $10-million endowment for programming and arts education at Santa Monica College’s performing arts center.

Born in New York on June 6, 1933, Broad was an only child who grew up in Detroit, where his Lithuanian immigrant father, Leon, worked as a house painter before operating several five-and-dime stores. His mother, Rita, was a seamstress who later worked as a bookkeeper for her husband.

The family name was spelled Brod and pronounced like the slang term for a woman, which made young Eli the butt of many jokes. This grew tiresome, so in junior high he added an “a” to his last name and told people “Broad, rhymes with ‘road.’“

“Some of the teasing continued,” he recalled in his 2012 memoir, “Eli Broad: The Art of Being Unreasonable,” “but it didn’t really sting anymore. I had changed myself.”

He graduated with a degree in accounting from Michigan State University in 1954, the same year he married Edythe “Edye” Lawson. In 1956 their son Jeffrey was born, followed three years later by another son, Gary. His wife and sons survive him.

At 20, Broad had become a certified public accountant — one of the youngest in Michigan history. He shared office space with Donald Kaufman, a carpenter-contractor who was married to his wife’s cousin. In 1957 he and Kaufman borrowed $25,000 from Broad’s father-in-law and launched a home-building company, Kaufman & Broad (now KB Home).

Broad had heard of a company in Ohio that beat its competition by building houses without the customary basement. “I didn’t understand why you couldn’t do that in Michigan,” he said in a 2006 Vanity Fair profile. “So we came up with a product, which I modestly called the Award Winner, which sold for $13,740, and vets could move into it for, like, 300 bucks. My idea was if they could move out of garden apartments into three-bedroom houses for less than rent and have equity and the tax benefits, it worked.”

His hunch proved correct. The houses sold quickly, and Kaufman & Broad became the biggest independent builder of single-family homes in the country. The company expanded into Arizona and California. Broad was a millionaire before he turned 30.

In 1963, after Kaufman retired, Broad moved the company from Phoenix to Los Angeles. He and his wife bought a home in Brentwood.

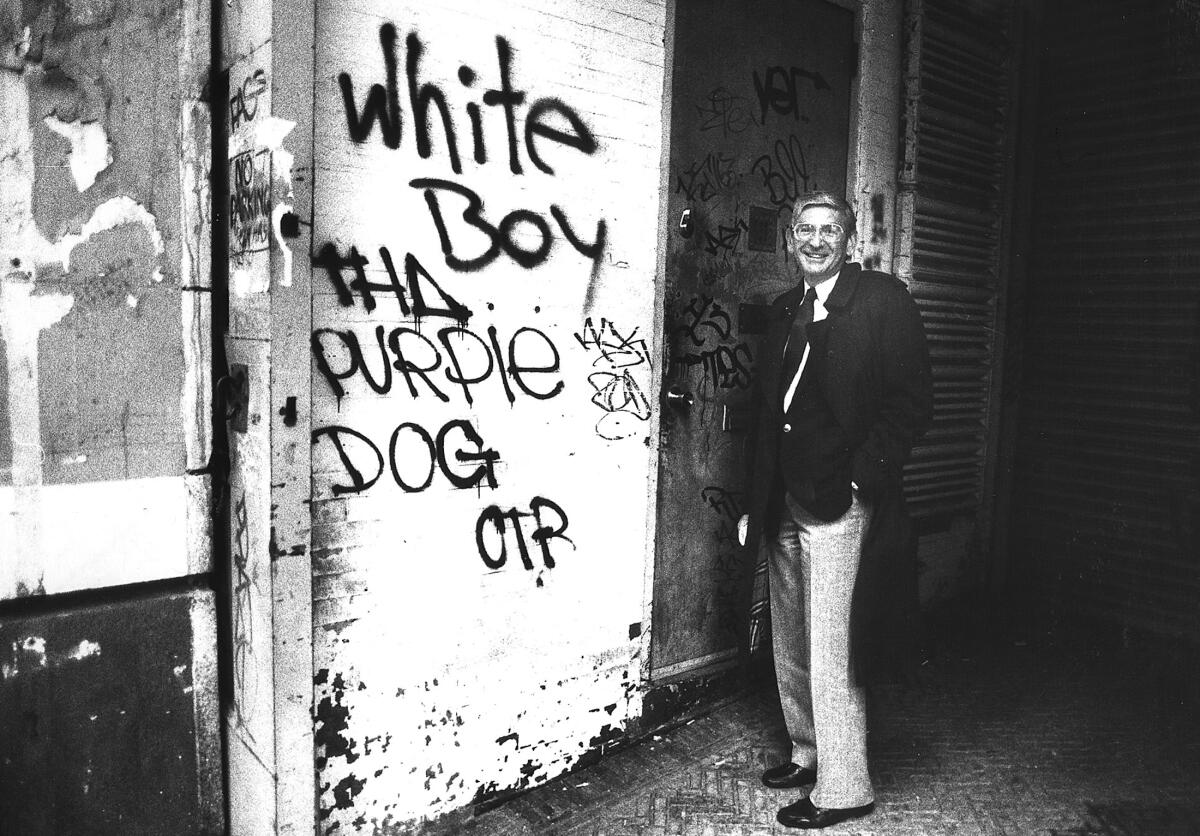

At first, Los Angeles, with geographic sprawl unlike Detroit or Phoenix, baffled him. But gradually he became a master of the metropolis, joining civic boards and elite social circles. Richard Riordan, the venture capitalist and future L.A. mayor, became a close friend.

“Los Angeles is a meritocracy,” Broad told Los Angeles magazine in 2003. “It’s one of the few cities you can move to without the right family background, the right religious background, the right political background, and if you work hard and have good ideas, you’re accepted.”

He got involved in politics, running California Democrat Alan Cranston’s first winning campaign for the U.S. Senate in 1968. Four years later, afraid that Democratic Sen. George McGovern was too soft on the Soviet Union, he served as vice chairman of Democrats for Nixon. Broad later led the successful effort to bring the 2000 Democratic National Convention to Los Angeles.

While he was building Kaufman & Broad, his wife, Edythe, immersed herself in L.A.’s gallery world. Before long her husband became an ardent collector too.

Their first major purchase came in 1972 when they paid $95,000 for a Van Gogh drawing. Broad eventually found modern art more to his liking and began accumulating works by such artists as Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst.

In the late 1970s, he led a campaign that raised more than $10 million to launch a museum dedicated to modern art. With a personal donation of $1 million, he became founding chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art and influenced the selection of Japanese modernist Arata Isozaki to design it.

In 1984, he stepped down as MOCA chair after disagreements with the board but remained one of the city’s most powerful art patrons.

In 1994, Riordan enlisted him to resuscitate the fundraising campaign for Disney Hall, which had been stalled by an economic recession. Riordan and Broad each contributed $5 million to the effort, and with Broad leading the charge the $135-million goal was reached by 1998. Despite a major tiff with architect Gehry, with whom Broad had a troubled history (Gehry designed his Brentwood home but was fired when Broad thought he was taking too long), the concert hall opened in 2003 to jubilant reviews. Broad received the lion’s share of credit for its completion.

Broad had a hand in a Renzo Piano building at LACMA, the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall and his own museum, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

His role in reviving the Disney Hall project established him as Los Angeles’ most formidable philanthropist. Los Angeles magazine put him on the cover in June 2003 with the headline, “He has more pull than the mayor, more art than the Getty, and more money than God. Does Eli Broad own LA?”

He acknowledged that people often questioned his motives. He liked putting his name on buildings and always sought the best return on his investments.

In 1995, he purchased a Lichtenstein painting called “I … I’m Sorry” for $2.5 million and paid with his American Express card, reportedly so he could rack up frequent-flier miles. He later donated the miles to California Institute of the Arts in Valencia for student travel. But the real reason for putting a seven-figure tab on his credit card, he said in his memoir, was to keep earning interest on the $2 million until the bill was due.

Strategic planning, as well as keeping a sharp eye on the bottom line, was what got him to the top of two industries. He had taken Kaufman & Broad into the life insurance business in the 1970s, when the housing market was in a slump. In the 1980s, he expanded into annuities and other financial services, which he eventually spun off into a separate company, SunAmerica. In 1993, he stepped down as chairman of Kaufman & Broad to run SunAmerica, his second Fortune 500 company.

In 1999, he sold SunAmerica to American International Group for $18 billion, and he retired in 2000 to become a full-time philanthropist.

The self-made billionaire, philanthropist and art collector used his wealth to mold Los Angeles’ cultural landscape.

Flush with cash from the sale, he committed $2 billion to his philanthropies, including $100 million to create the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, which supports school reform. It has spent more than $600 million since 1999 on a variety of initiatives.

As with the arts, Broad demanded a hands-on role in improving education.

He played a prominent role in the development of the Los Angeles Unified School District’s downtown arts high school. He personally helped recruit two superintendents, former Colorado Gov. Roy Romer and veteran educator John Deasy. But his ambitions ranged beyond L.A. and California.

In 2002, his foundation began to fund the Broad Prize, which targeted urban districts with large achievement gaps. It exemplified its founder’s philosophy of tying monetary awards to concrete results such as gains in student test scores. Disappointed in the slow pace of improvement, he suspended the prize in early 2015.

He also founded the Broad Superintendents Academy, the largest training program in the nation for urban school superintendents. Its more than 150 fellows, many of them from business, the military and other fields outside education, undergo a 10-month program heavy on corporate-style management techniques and have gone on to leadership positions not only in Los Angeles (Deasy is a Broad graduate) but also in New York, Chicago and other major city school districts. In 2019, Broad announced he was moving the academy to Yale University.

The wealth and vision that created these initiatives also made Broad a target of scorn by some education experts. One of his most prominent critics was education historian Diane Ravitch, who assailed Broad along with Microsoft’s Bill Gates and others as members of “the billionaire boys’ club” of business titans whose top-down reform efforts weaken the voices of parents and teachers unions.

“His Broadies are leading districts and states,” Ravitch wrote in her blog in 2012. “Some are educators, some are not. Some are admired, some are despised. But the question remains, who elected Eli Broad to reform the nation’s schools? He is like a spoiled rich kid in a candy shop, taking what he wants, knocking over displays, breaking jars, barking orders.”

None of this discouraged Broad. “Our role is to take risks that government is not willing to do,” he told Newsweek in 2011. “The fact that I don’t concern myself about criticism or pushback helps.”

Broad made an offer to buy the Los Angeles Times and San Diego Union-Tribune in 2015, saying he believed the papers should be owned by a Californian. His offer, which had reportedly been solicited by Tribune Publishing, was rejected. The newspapers were later purchased by Soon-Shiong, a Los Angeles biotech billionaire.

Notoriously impatient — ”Let’s move on” was his favorite way of telling people they were wasting his time — Broad liked to stay busy, multitasking even during his leisure time. The only regret he expressed about an extraordinarily successful life was that he spent too much time building his businesses and not enough time being a father to his sons, neither of whom has sought the public spotlight.

“I was serious, focused, demanding, and not much fun,” Broad wrote in his memoir. “I took the boys with me to tour subdivisions, and now I realize that’s not exactly how kids want to spend their weekends. I missed too many moments.”

“I am unreasonable,” he wrote. “It’s the one adjective everyone I know — family, friends, associates, employees, and critics — has used to describe me…. But I believe that being unreasonable has been the key to my success.”

Woo is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Steve Marble contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.