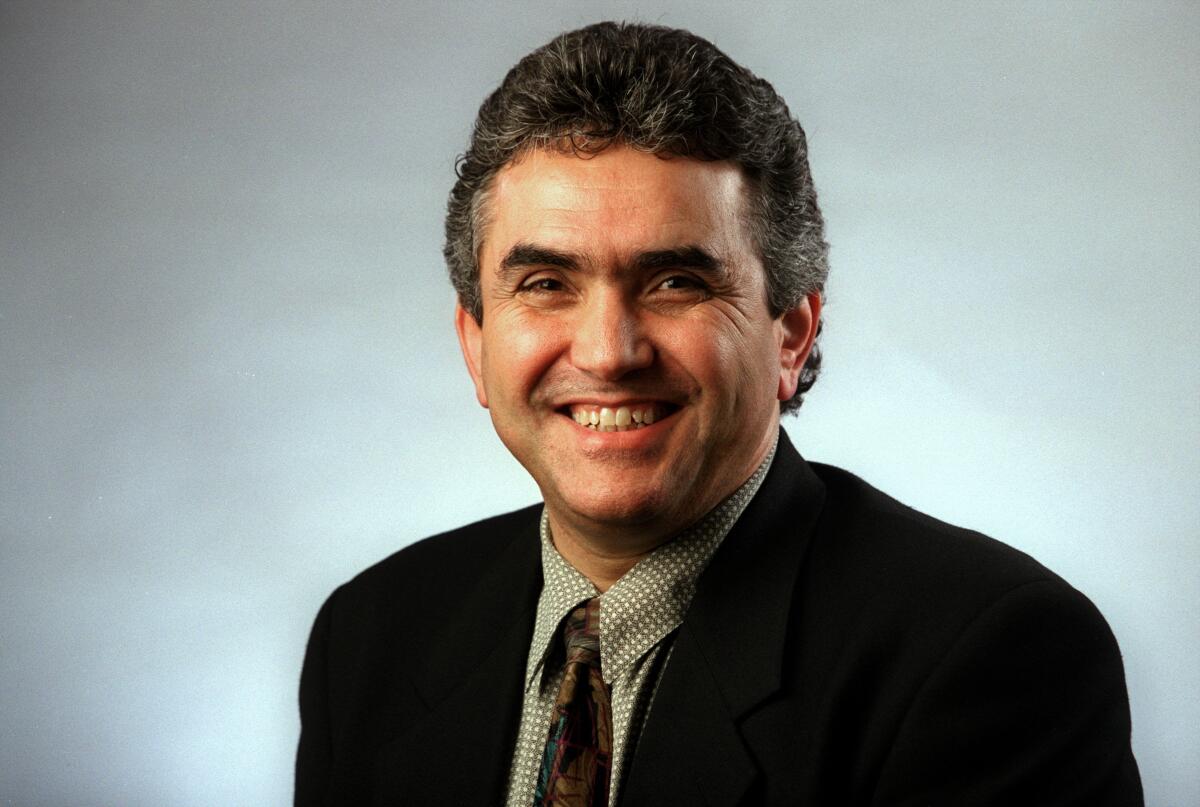

Agustin Gurza, a former Times columnist and influential Latin music critic, dies at 73

- Share via

Former Los Angeles Times columnist Agustin Gurza, a onetime record store owner who became a groundbreaking chronicler of Latino life in Southern California and one of the country’s leading critics and historians of Spanish-language music, has died.

Gurza died Saturday morning after suffering a heart attack, according to his wife of 19 years, Rosie Caballero Gurza. He was 73.

Gurza was a 20-something UC Berkeley graduate when he stepped into the office of then-L.A. Times music editor Robert Hilburn in 1976, looking for a reporting job. Hilburn didn’t need a reporter, but he was desperate to find someone to write reviews. He told him to pick a record and write 100 words.

“But I’ve never done a review,” said Gurza.

“But you care about music. That’s all that matters,” Hilburn recalls saying.

Gurza delivered the review of a band called the Salsoul Orchestra and dozens of others over the next few years, kick-starting a wide-ranging career of columns, books and reviews. They featured his deeply engrossing writing style that could float readers along with its beauty, humor and at times bitingly critical prose. The writing was elegant but direct, decidedly unfancy, and always infused with Gurza’s encyclopedic knowledge of music and passion for social justice, community and family.

Over the following decades, Gurza went on to become a columnist in Orange County, first for the Orange County Register, then for The Times’ Orange County edition. He was among the first Latino columnists in Orange County, inspiring a generation of young Latino journalists.

“Agustin was someone to me who epitomized the joy of life itself,” said Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, who was in college when he started reading Gurza’s column. Arellano remembers thinking: “This is a guy who knows his music, loves his music, but also loves the ambiente of being Latino, of the pride.” Gurza, he said, knew that “what he covered was a prideful thing and that the wider world should know it.”

By 2001, Gurza was back at The Times writing about the Latin music explosion. He profiled music stars like Shakira, Ricky Martin and Daddy Yankee, and quickly became one of the most influential critics in the country. He was a fierce traditionalist whose tastes were shaped by the boleros and corridos of his youth, but he also embraced the more modern, rock- and rap-infused Latin music genres. Though he championed many artists, many were not spared his critic’s wrath, not even the musical stars who became his friends.

Ruben Blades, the salsa music legend and Hollywood actor, was one of them. Gurza considered him among the most important songwriters in Latin pop music history, but didn’t hesitate to criticize some of his works. The two men, both known for their roaring expressions of passionately held opinions, often clashed over dinner and glasses of whisky, so much so that Blades referenced Gurza in his 1984 song “Desapariciones.”

Es un buen muchacho (He’s a good guy)

A veces es terco cuando opina (He’s kind of stubborn with his opinions)

Years later, Gurza flew to Panama to interview Blades, who had been appointed the country’s minister of tourism. Gurza couldn’t help himself, delivering what appeared to be a good-natured jab back at his old friend.

Blades can be funny, generous and charming, an engaging storyteller who enlivens anecdotes with hilarious impersonations. But he can also be stubborn…

Gurza was born in the Mexican state of Coahuilla, but moved to San Jose as a toddler. His father was a music-loving doctor, his mother a piano-playing homemaker. Gurza’s almost obsessive passion for music was apparent very early, when he would accompany his father to music stores to comb through the stacks of records, said Gurza’s brother, Dr. Edward “Lalo” Gurza, a retired internist from Chicago.

“My father would spend hours in record stores going through every single cabinet, which drove my mother nuts. Agustin had exactly the same habits,” said Ed Gurza in an interview.

After graduating from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism in 1974, Gurza moved to Los Angeles and opened a record store in East Los Angeles. He was right at home in the cluttered space filled wall to wall with recordings. He eventually closed the shop, but his record-store decor aesthetic lived on. Everywhere he lived afterward, he filled his living rooms, offices and garages with thousands of records, ranging from his rock favorites like Bob Dylan and the Beatles to Latin music legends like the Puerto Rican band El Gran Combo and Celia Cruz.

Though his primary passion was music, by the mid-1990s Gurza was working as a columnist in Orange County at a time when the experiences of Latinos in the area were largely underreported. He fought to preserve murals, gave voice to immigrant mothers, took on politicians and expressed weariness, in 1999, over Orange County’s heated political battles over immigration in a column that seems prescient today. “We reach temporary standoffs, but minds don’t change, hearts don’t open,” he wrote.

“He was a lone voice in the wilderness for years,” said Arellano. “He was defending us in a place where we needed a lot of defending.”

Arellano himself was criticized by Gurza, who believed Arellano’s popular “Ask a Mexican” column perpetuated stereotypes, with Gurza calling him the “Paris Hilton of Latino journalism.” But Arellano said Gurza’s overarching commitment to the Latino experience transcended any personal rivalry.

Though his writing was often loaded with slashing commentary, Gurza was a charming and fun-loving raconteur who could disarm his fiercest critics with his constant smile, hair-trigger laughter and deep repertoire of salsa dance moves which he liked to show off at nightclubs across Los Angeles.

Gurza’s return to music writing in 2001 coincided with a resurgence of Latin music across the country. He covered the flash and the controversies, but also wrote about little-known regional styles, like son jarocho from the Mexican state of Veracruz, making them relatable and understandable to readers.

“I admired that about [Gurza]. He was one of very few Latino writers in all of the U.S. that was considered an important opinion maker,” Blades said in an interview. “I could always count on him to provide a perspective that would always help us understand better the issue.”

After he took a buyout from The Times in 2008, another musical adventure was awaiting him. UCLA had taken possession of the world’s largest archives of recorded Spanish-language music and needed someone to write about it. The archive, called the Arhoolie Foundation’s Strachwitz Frontera collection, at the time had 90,000 recordings, much of it from Mexican artists.

“I swear he listened to every song,” said Chon Noriega, a professor at the UCLA department of film, television and digital media. Noriega asked Gurza to write a 100-page book; Gurza delivered an award-winning 234-page book and continued to write about the collection in a blog. The writings are a marvel of storytelling as Gurza’s exhaustive research illuminates the tales of the places, personalities and histories behind the songs. Gurza infused much of the writings with memories of his childhood and loving portraits of family members.

His last posts focused on recordings of boleros, aching songs of romance from Latin America that were among his favorites. Always a purist, he bemoaned how some had been drained of soul by the clutter of overproduction, comparing it to how famed rock producer Phil Spector, in his opinion, suffocated some of the Beatles’ songs with his wall of sound.

When he was a kid, Gurza recalls, his brothers and sisters would make fun of him for liking traditional music that they considered corny. But Gurza’s love of the ballads only deepened with time. His wedding in 2002, he said, featured a bolero, “Somos Novios,” that, Gurza notes, was one of the most covered Spanish-language songs of all time after it was translated into English and retitled “It’s Impossible.”

“The bolero, like love itself, is eternal,” Gurza wrote.

Gurza is survived by his wife, Rosie; sons Miguel, 40, and Andres Agustin Gurza, 19; brothers Dr. Eduardo Gurza, Guillermo Gurza, Roberto Gurza and Alejandro Gurza; and sisters Mary Esther Gurza Fowler, Guadalupe Gurza Witherow and Patricia Gurza Dully.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.