The reality of rationing

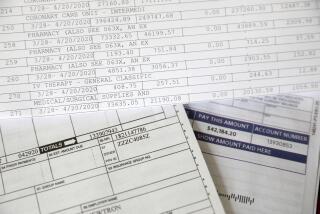

Opponents of the main Democratic proposals for healthcare reform warn that consumers would be stopped from getting the care they need when they need it. President Obama’s plan is “rationing,” one political strategist blogged. It’s an unrealistic criticism, yet policymakers shouldn’t sugarcoat reality: Rationing is part of the healthcare system today, as it will be under any overhaul fashioned by Washington. That’s no argument for sticking with the current approach, however. Without significant improvements in the way healthcare is delivered and paid for, the escalating costs will cut off more people from the care they need.

The current system rations care by income, an approach that leaves millions of people who have limited resourcesand no insurance with few options beyond free clinics and emergency rooms. This situation is acceptable to many (especially the well-insured) because it doesn’t involve the government deciding which treatments doctors can provide or which procedures insurance companies can pay for. Instead, services are available to anyone who can afford them, much as food and shelter are, with the safety net of Medicaid to support the poorest Americans.

Still, there is some government rationing. Washington and the states limit eligibility for Medicaid to the indigent, excluding many of the working poor who aren’t covered by their employers. And the reimbursement rates for government insurance plans -- Medicaid in particular -- are set so low, a diminishing number of doctors and hospitals participate. Those patients have to travel farther and wait longer for care.

Critics of the healthcare reform bills now moving through Congress insist that more extensive rationing would result if Congress created a Medicare-style, government-run insurance plan to compete with private insurers. Another likely source of rationing, they say, would be a government-led effort to compare the effectiveness of different treatments. They point to Britain’sNational Institute for Health Clinical Excellence, which has denied funding for selected drugs, surgeries and diagnostic treatments that didn’t meet its threshold for value.

Both of these arguments are hyperbolic and at least a little bit misleading. Although we’d prefer a government-run insurance option that has to negotiate with doctors and hospitals the same way private insurers do, we don’t believe that one with the power to set prices will necessarily out-compete the likes of Aetna, Kaiser Permanente and Blue Cross. That’s because private insurers will still be able to innovate with providers to deliver better care, just as FedEx and United Parcel Service have done to compete successfully with the U.S. Postal Service. And even if the “public option” somehow monopolized the market, recent history shows that the likely result would be more procedures and treatments being covered, not fewer. Politicians simply can’t resist the backlash that invariably results from attempts to limit their constituents’ access to healthcare services. For example, Congress enacted a healthcare planning bill in 1974 to deter duplicative or excessive spending, only to repeal it the following decade in the face of public protests.

As for comparative effectiveness research, Washington’s efforts thus far have been focused on filling the huge gaps in knowledge about how best to treat various ailments. It’s a process that will take years, but the promise is that patients and their doctors will be better able to compare treatments in terms of outcome and cost, leading to higher quality care. The work can also help reduce spending by curbing wasteful procedures. Granted, the idea raises the specter of bureaucrats setting age limits for hip replacements or ruling out some unconventional treatments for life-threatening illnesses. But federal and state governments already have that power over the Medicare and Medicaid programs, which hasn’t stopped the rapid introduction of new treatments and techniques. And unlike the British government, which not only provides insurance but employs the providers, ours can’t cap healthcare spending or bar the private sector from providing services simply because they’re too expensive.

We don’t think Washington should have the power to set a national budget for healthcare, and none of the bills moving through Congress contemplate that. But if Congress doesn’t get serious about controlling healthcare costs, future generations may not be able to avoid such draconian limits. Left unchecked, healthcare spending could consume a quarter of U.S. gross domestic product by 2025, and half by 2082, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates. If you’re looking for something to fear about healthcare in the future, that data is where you will find it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.