On policing, New York should look to L.A.

New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg on Monday insisted that his city’s “stop and frisk” police practices were constitutional, despite a federal judge’s finding that they were racially discriminatory and violated the 4th and 14th Amendments. But it’s almost beside the point whether Bloomberg is on solid legal ground and whether his appeal can succeed. New York’s confrontational approach to law enforcement has bought short-term results at the cost of alienation and resentment, and its leaders would be wise to let the trial court’s ruling stand — and to learn a lesson from Los Angeles.

For decades, this city mastered the dark art of enforcement by intimidation. The Los Angeles Police Department cultivated an us-versus-them relationship with African American and other nonwhite neighborhoods and employed brutal tactics that, even when legally defensible, were destructive to the city. The daily affronts to residents’ dignity, the car stops, the searches, the killer chokeholds, the sweeps and roundups, and the unequal and unjust treatment from officers stoked anger that resulted in violent outbursts in 1965 and 1992, and still couldn’t keep gangs from growing or crime from bleeding into the white, well-to-do and formerly comfortable and confident areas of the city.

Some law enforcement leaders here came to see the futility of policing the way an occupying army patrols conquered territory. There were enlightened and innovative LAPD captains and lieutenants and patrol officers who saw firsthand the need for change. But a community policing model that emphasized engagement over containment had little staying power until a federal lawsuit, oversight under a consent decree and the hiring of William J. Bratton as chief. Together with advocates, criminal justice experts and elected officials, and based on the lesson he learned from leading (ironically) the NYPD, Bratton laid out a path for the LAPD that put officers in regular and constructive contact with community leaders, former (and current) gang members, interventionists and other would-be peacemakers. Los Angeles established an Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development that, among other things, helps neighbors mediate disputes before they become violent turf battles. The current police chief, Charlie Beck, who grew up in the old LAPD, now champions and furthers reforms.

Los Angeles’ progress in policing is no mission accomplished. At least one study of the reformed LAPD found higher rates of stops, frisks, arrests and searches of blacks and Latinos than of whites. But Los Angeles appears to be on a more constructive path, and the results are sufficiently promising that other cities have taken note and asked for advice.

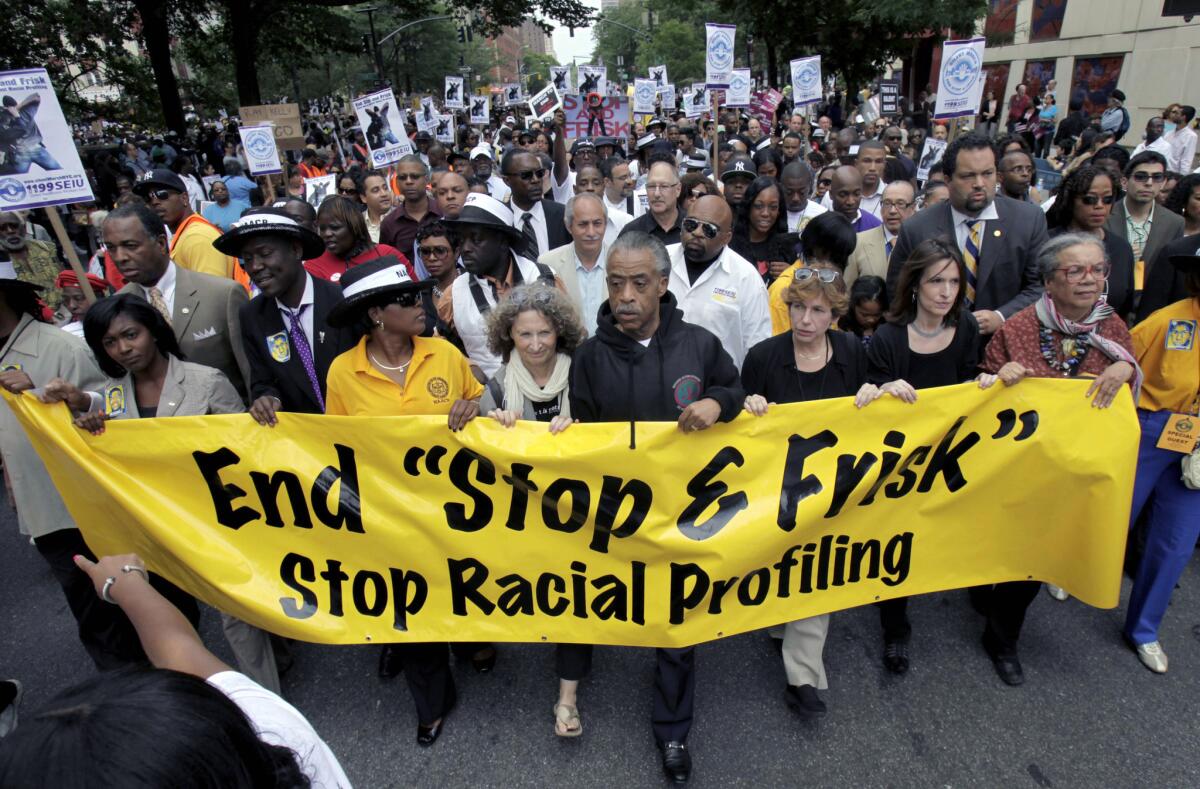

Of course, they’re watching the New York experience as well. That model includes thousands of seemingly random stops and frisks, mostly (83%) of African American and Latino New Yorkers; followed by community resentment, lawsuits and, as of Monday, findings of unconstitutional policing. That story is familiar to anyone who has lived in Los Angeles longer than a decade.

Defenders of the New York approach point out, correctly, that violent crime in the city plunged at the same time it stepped up its aggressive techniques. But so has it plunged in Los Angeles, as this city has sought to engage and respect the communities it patrols. Of the two models, the L.A. way looks more sustainable — on the streets and, perhaps, in the courts.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.