Opinion: The Supreme Court can’t save Trump from impeachment

- Share via

It’s unclear whether the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives will ever try to impeach President Trump, but this week Trump warned that he has a plan to stop any such inquiry. On Wednesday he tweeted that “if the partisan Dems ever tried to Impeach, I would first head to the U.S. Supreme Court.”

This threat was remarkable for its irony: Trump, who has fumed over judicial review of his policies, is now suggesting that he would seek judicial intervention to save his presidency.

But his plan to “head to the U.S. Supreme Court” also demonstrates that the president has a shaky grasp of the law. (Not that this comes as a surprise. Remember when Trump threatened as a candidate to “open up” our libel laws, apparently unaware that libel is governed by state, not federal, law?)

The bad news for Trump is that the consensus of legal experts, blessed by the Supreme Court, is that impeachment is none of the court’s business. (The chief justice, however, does preside at Senate impeachment trials for a president.)

In his classic work “Impeachment: A Handbook,” the late constitutional scholar Charles L. Black Jr. heaped scorn on the idea that the court could review an impeachment and removal of a president.

Presenting a scenario in which the court overrides the judgment of Congress and reinstates the president, Black wrote: “I don’t think I possess the resources of rhetoric adequate to characterize the absurdity of that position.”

Black went on to point out that the Constitutional Convention “after debate and over prestigeful opposition, moved impeachment trials out of the Supreme Court and into the Senate.”

The Supreme Court itself has strongly suggested that it agrees with Black’s bottom line.

In 1993, in the case of Nixon vs. the United States (no, not that Nixon), the court unanimously rejected a challenge to the impeachment and removal of a federal district judge. The former judge, Walter L. Nixon, had argued that his impeachment trial was tainted because the Senate established a committee to receive evidence and take testimony. That process, he argued, violated the Constitution’s requirement that the Senate as a whole “try” impeachments.

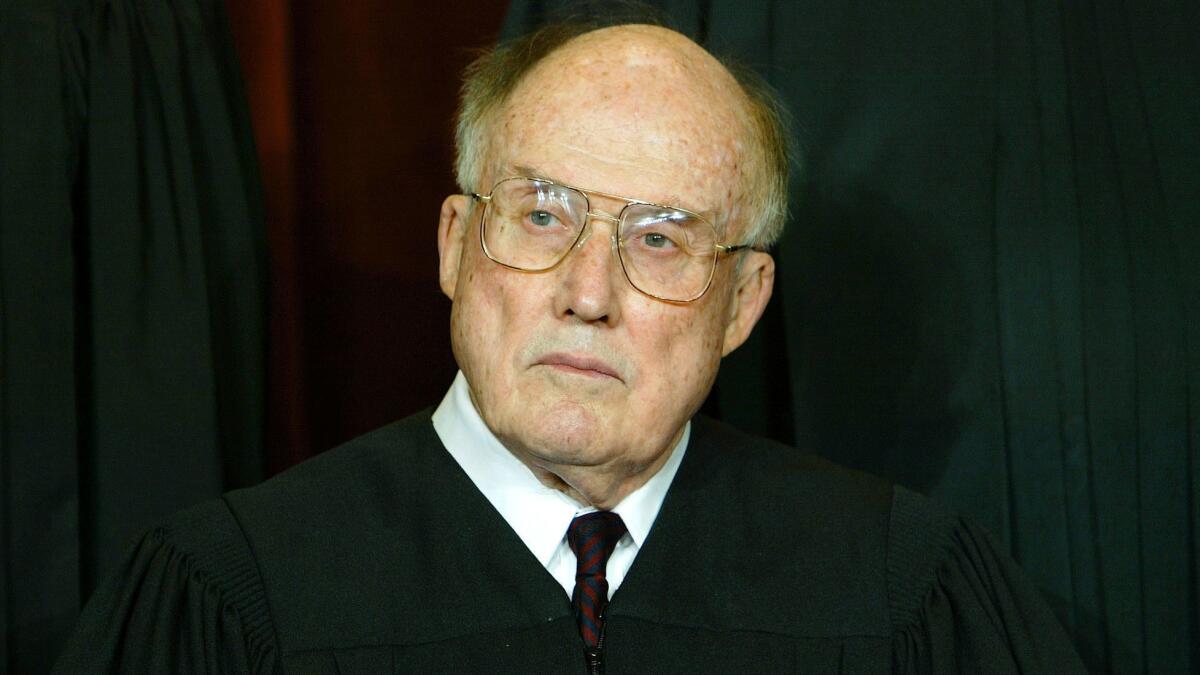

Writing for himself and five other justices, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist said that Nixon’s claim was “nonjusticiable” — that is, a political question beyond the court’s authority.

“The history and contemporary understanding of the impeachment provisions support our reading of the constitutional language,” Rehnquist wrote for the court. “The parties do not offer evidence of a single word in the history of the Constitutional Convention or in contemporary commentary that even alludes to the possibility of judicial review in the context of the impeachment power.”

Three justices who concurred in the result declined to sign Rehnquist’s opinion. Justice Byron White, joined by Justice Harry Blackmun, would have left the door open a bit to lawsuits to ensure that the Senate “adhered to a minimal set of procedural standards in conducting impeachment trials.”

Writing only for himself, Justice David Souter suggested that judicial review on impeachment might be justified if the Senate “were to act in a manner seriously threatening the integrity of its results, convicting, say, upon a coin toss, or upon a summary determination that an officer of the United States was simply ‘a bad guy.’”

Only one of the justices who participated in Nixon vs. U.S. — Clarence Thomas — is still on the court, but Rehnquist’s majority opinion is a precedent. Its existence would seem to dash Trump’s hopes of asking the court to intervene in a process he might consider another “witch hunt.”

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.