When Kadafi commanded respect

Watching from afar as Moammar Kadafi’s control crumbles in Libya, I was reminded of the events of March 1974. It’s hard to remember today, but there was a time when the Libyan leader commanded great respect in the Middle East, and that spring he was at the height of his power.

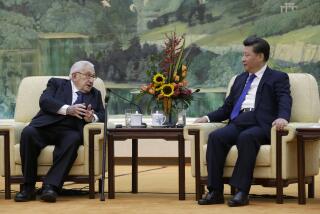

The mercurial dictator, whose country was sitting on a lake of oil the size of Alaska, had been the first to declare an oil embargo against the United States after President Nixon asked Congress for $2.2 billion to resupply Israel’s armed forces during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. The other Arab nations in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries eventually joined the Kadafi embargo, and Henry Kissinger was working hard behind the scenes to try to end it.

At the time, I was a Los Angeles Times correspondent based in the Middle East, and I was dispatched to Cairo to cover the next OPEC meeting, which was expected to be a gauge of whether Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy was working.

Kadafi refused to attend the meeting, insisting that any meeting to consider lifting the embargo should be held in Tripoli.

After two days of haggling behind closed doors, OPEC members announced that the meeting was moving to Tripoli the next day, a development that left hundreds of news correspondents, diplomats and oil industry observers scrambling to book flights and accommodations.

I managed to snag a first-class aisle seat on Lufthansa, and I was enormously pleased when the oil minister from one of the smaller gulf states, clad in robes and headdress, took the window seat next to me. After we were airborne, I introduced myself: “I’m William Coughlin of the Los Angeles Times.” “Los Angeles?” he said. “I went to UCLA.”

I put out my hand. “Stanford,” I said, and then asked the obvious question: “Can you tell me why we all are so abruptly airborne on the way to Libya?”

“We’ve reached a decision, nine to one, and to please Kadafi we are going to announce it in Tripoli.”

“And what was the decision?

“We’re going to lift the embargo.”

“Who was against it?”

“Kadafi, of course.”

Not wanting to push my luck, I launched into a discussion of Pacific Coast football, interrupting the conversation only once, to go ask the stewardess where the plane was going next. “Tunis,” she replied, telling me there was space on the flight and I could remain on board. I was relieved, knowing I’d never be able to call in my OPEC scoop from Tripoli.

In Tunis, I sent my story without any problem, and it ran on the next day’s front page. Meanwhile, I headed back to Tripoli to cover the official announcement. When I arrived, I learned that Kadafi had decided he didn’t want the news announced in his country. It was to be delayed until the weekend and announced in Vienna, where the Arab oil ministers were scheduled to meet with their non-Arab OPEC partners.

Wherever Kadafi is now, I doubt he’s being treated with that kind of deference.

William J. Coughlin, a Pulitzer Prize winner, was Middle East bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times for five years.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.