‘Plug-in volunteering’ doesn’t cut it

- Share via

Monday, millions of Americans will honor the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. by volunteering for community service. They will collect cans of food for the poor, ladle soup for the hungry and help the homeless. They will talk about their rewarding experiences, and the people they help will express their gratitude. Tomorrow, everybody will return to their normal routines.

The MLK Day of Service represents an increasingly popular form of volunteerism — setting aside a day or so to help the needy. “Plug-in volunteering,” as I call it, is the essence of Big Sunday, Make a Difference Day, Family Volunteer Week and other large-scale efforts. Short-term service accounts for nearly half of all volunteer activity in America. It serves many modern-day purposes: We’re making a contribution without taking too much time from our jobs and families, adding a line to our curriculum vitae or satisfying a community service requirement. And, of course, we’re sometimes giving temporary aid to the needy.

But this all has little connection with the historical meaning of volunteering because it lacks the power to bring about social reform. Early advocates saw the role of volunteerism in promoting reform as an important goal and as a cornerstone of democracy. We must return to this view and become more mindful of the sources of the larger problems, so we can work toward fixing them.

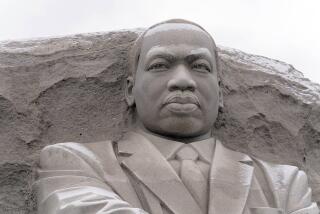

PHOTOS: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. -- and the civil rights struggle

A 1902 essay by Jane Addams, a pioneering volunteer, spotlights the dangers of plug-in volunteering. In it, she recalls an experience from her first years of volunteering, in which she was asked by poor immigrant parents if their children should quit school to go to work to save the family from homelessness, and she said yes. Looking back with shame years later, she realizes that the family should not have had to choose between their children’s education and shelter.

To resolve such dilemmas, Addams connected her volunteer work to large-scale political reform. In contrast to the “charity visitor” she had been when she was young, Addams came to believe that a good volunteer must open herself to deeper “perplexity,” to discover if a problem has social causes that can be remedied.

The plug-in volunteer is today’s version of the charity visitor and is the antithesis of Addams’ ideal. These volunteers expect to “change the world one X (pick one: plastic bag, diaper, can of tuna) at a time” without wondering about the bigger picture.

I studied a network of nearly 100 youth organizations — mainly after-school programs for disadvantaged youths — in a mid-size Midwestern city. One of the network’s missions was to encourage volunteer work. I found that when youth volunteers organized King Day projects, their adult supervisors did not encourage them to ask the big question about why the people were so needy to begin with. This finding typifies plug-in volunteering.

Unsurprisingly, most volunteers came away with the impression that however many cans of food they had gathered, there would always be hungry people. Feeling hopeless, they in effect accepted the status quo.

We can restore Addams’ ideal by remaking the organizations that encourage plug-in volunteering. The vast majority of them are nonprofits with paid staff and short-term funding from multiple donors. To ensure future funding, organizers express success in short-term “measurable outcomes,” as in “tons of food for the needy,” “number of volunteers” and “numbers of people served.” If helping the needy is their goal, organizations need more flexible time lines for achieving results and digging deeper, to learn if numbers are the only way to measure success.

In the more immediate term, volunteers should see plug-in volunteering as only a tiny first step in a long process of walking in the shoes of others, not as a solution to recipients’ problems. They should talk to one another, for example, about whether the people they are feeding this week will be hungry again next week. They might then start talking about finding steady money to pay for their food, and that could lead eventually to something bigger: social reform.

Like Addams, King connected volunteering to political activism. On a day honoring his birthday, we can begin to bridge the imagined divide between caring about people and caring about politics.

Nina Eliasoph, an associate professor of sociology at USC, is the author of “Making Volunteers: Civic Life After Welfare’s End.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.