Populism from unlikely candidates

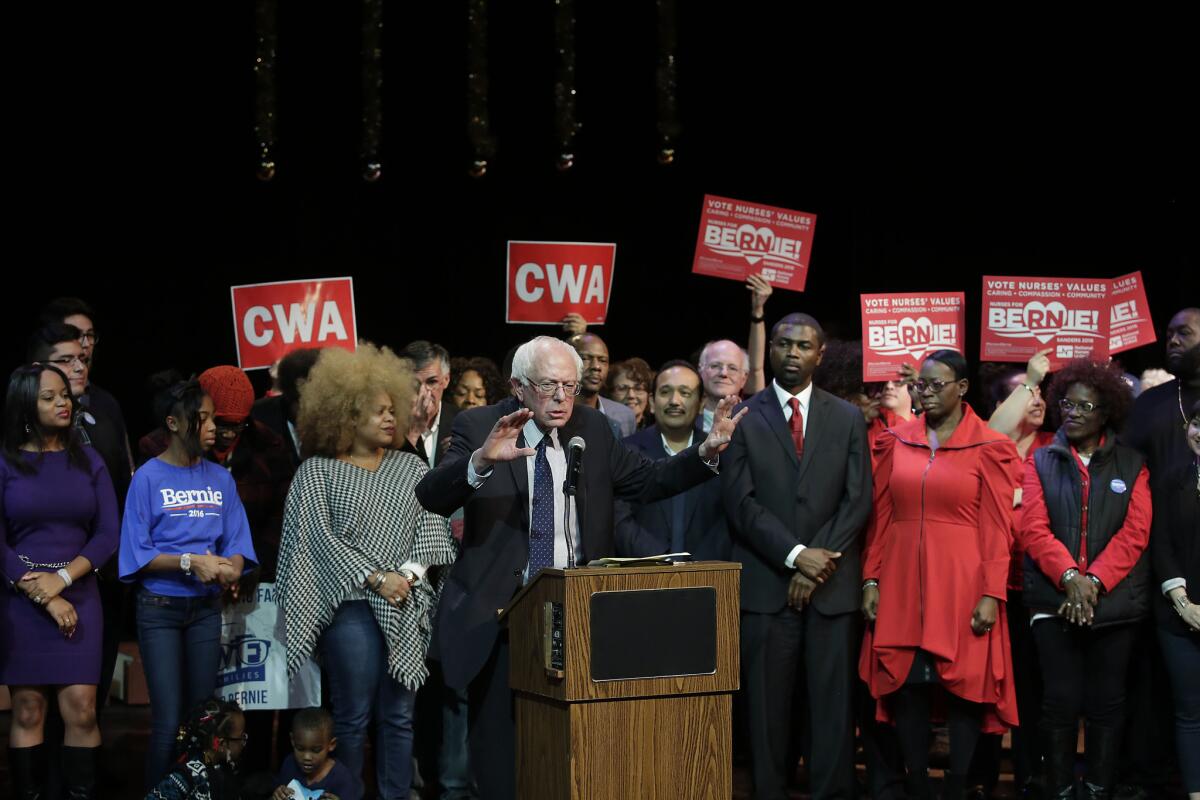

Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders speaks during a news conference on Dec. 23 in Chicago.

- Share via

Populism is typically born in places like Nebraska, Louisiana, Kansas and the other bits given short shrift in that famous Saul Steinberg New Yorker cartoon showing the view of the world from 9th Avenue.

It’s not supposed to hail from Brooklyn or Queens, never mind Burlington, Vt., or midtown Manhattan. But that’s where the two reigning populists of the 2016 cycle call home.

You could say that Donald Trump, the son of a rich real estate developer in Queens, was always a populist at heart. All his life he wanted to break into the fancy-pants world of Manhattan real estate. Despite his wealth, he still has that bridge-and-tunnel chip on his shoulder. And that chip explains the garishness of his publicity-seeking lifestyle, as well as his politics.

Looked at through an historical lens, a billionaire Manhattanite from Queens and a Jewish socialist from Brooklyn should be standing at the pointy end of ... pitchforks.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders grew up in Brooklyn, the son of Polish Jewish immigrants. He followed a somewhat familiar path to politics: As Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina quipped in one of the recent Republican debates, Sanders went to the Soviet Union on his honeymoon and never came back. In reality he ended up in Burlington and became the socialist mayor of one of the very first latte towns.

Looked at through an historical lens, a billionaire Manhattanite from Queens and a Jewish socialist from Brooklyn should be standing at the pointy end of the pitchforks, not leading the mobs holding them. Nearly all of the famous populists hated the East Coast, the super-rich and the big cities. A good number — but not all — of them disliked Jews.

And yet, East Coast populism is here.

It’s a fantastic moment to compare and contrast, as they used to say in school.

If you can ignore the fact that he’s a billionaire who brags about having been part of the corrupt political system he promises to overthrow, Trump resembles some of the great populists of yesteryear. He’s a nationalist who promises to restore the country to the greatness his followers nostalgically desire. He’s a nativist whose one core issue is stopping illegal immigration — and now any immigration of Muslims, “temporarily.” And he’s a consummate panderer, — or, if you prefer, “fighter” — who channels and validates his supporters’ frustrations. As the fictionalized Huey Long character Willie Stark says in the novel “All the King’s Men,” “Your will is my strength. Your need is my justice.” Long promised to make “every man a king.” Trump promises to make everyone a winner.

Sanders, meanwhile, is all about populist economics — literally. With the exception of his pacifism, he is almost incapable of talking about anything else. But his worldview would be totally recognizable to William Jennings Bryan or Long or even Father Charles Coughlin. According to populist economics, the rich exploit the poor and the middle class intentionally. They leach off their hard work, and they send them to war.

The proper role for populist-run government is to make them pay, literally and figuratively. Our economy is “designed by the wealthiest people in this country to benefit the wealthiest people in this country at the expense of everybody else,” Sanders insists. The “billionaire class” has rigged it all.

This is one place where Sanders and Trump overlap. They want to make the people ruining this country pay. Sanders wants to impose a cartoonish “speculation” tax on Wall Street; Trump wants to make the Mexicans pay for the wall that will keep them out.

The one area where Trump and Sanders break totally with populist practice (other than geography) is religion. Nearly all of the famous heartland populists of yore were steeped in religion and spoke its language fluently. Long’s “Share the Wealth” plan, for instance, was vaguely derived from the Bible.

Sanders is a “not particularly religious” Jew who hates to talk about religion. Trump, because he’s seeking the GOP nomination, has had to work hard at faking religious sincerity. But even if he were serious that he won’t share his favorite Bible verse because “that’s personal,” his reluctance would distinguish him from traditional populists.

That may be a sign of the times. Or it may just be the kind of politics you get when you start a populist prairie fire so far from the prairies.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.