Op-Ed: Instead of shaming non-voters, let’s make voting easier

Every election season, we hear a similar message: People who don’t vote are failing to fulfill their civic duty. It has been particularly loud in the lead-up to this year’s midterm.

That’s understandable. We are facing a future in which millions may lose healthcare and rising temperatures could result in ecological disaster. Meanwhile, our government is setting up detention camps for children at the border.

If you don’t care about all of this enough to vote, the logic goes, you must be entitled, selfish and morally bankrupt. Certainly this was many people’s reaction to a widely read New York magazine article about 12 young people who said they might not vote.

The problem with getting angry at non-voters is that, in many cases, non-voting isn’t an individual moral failure. The United States has long embraced policies that create barriers to voting. Framing all non-voters as privileged jerks shifts the criticism away from the people who are working to prevent citizens from voting.

Voting in America is unnecessarily difficult, often by design.

America has a long history of voter disenfranchisement. At the beginning of the republic, only property owners were allowed to vote. White women didn’t gain the right to vote until 1919. Black men and women didn’t get the right to vote until 1965.

This tradition of disenfranchisement continues today. In many states, felons lose voting rights. It is no coincidence that the people convicted of felonies and incarcerated in the criminal justice system are disproportionately African American.

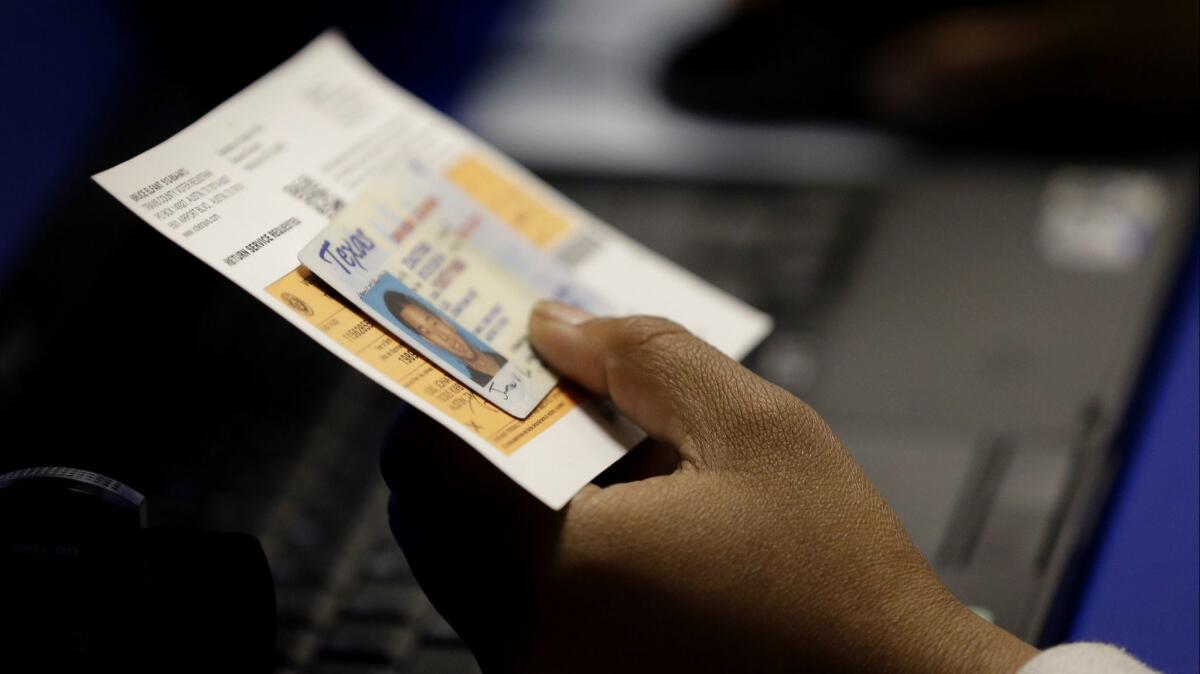

Voter-ID laws also target marginalized voters, who are less likely to have driver’s licenses or other forms of state identification. One such law in North Dakota requires voters to have a current street address, which amounts to a significant barrier for many residents of Native American reservations, where it is common to have only a Post Office box.

Barriers to voting for marginalized citizens may seem distinct from the barriers faced by non-voters who have the right to vote but simply don’t bother. But disenfranchisement works on a continuum. Some policies explicitly exclude marginalized people from voting; others make voting more difficult.

If you have resources, education and free time, it’s relatively easy to pay attention to politics. If you’re constantly struggling to make ends meet, it’s more difficult.

Similarly, voting may seem like a small commitment of time and money. But if you are an employee who can’t get time off work without losing an hour or two of pay, the hurdle is much higher.

This helps to explain why, in the 2014 midterm elections, 75% of people making less than $10,000 a year and 69% making less than $30,000 didn’t vote. At the other end of the income scale, people who made more than $100,000 — 22% of the population — composed 30% of voters in the 2014 midterm elections.

When you make voting more difficult, you discourage less affluent voters. Republicans in Wisconsin passed strict voter ID laws in 2016. Sure enough, the law disproportionately affected poor, often black voters, driving down turnout in urban areas and possibly costing Clinton the state.

Even basic bureaucratic requirements, such as voter registration, reduce turnout. Countries with automatic voter registration — Canada, for instance — have much higher voting rates than the United States. The Pew Research Center recently found that the United States trails other developed countries when it comes to voter turnout, ranking 31 out of 34.

The news media often show images of long lines at the polls as a sign of a healthy democracy and committed citizens. But long lines at the polls are actually a sign that democracy is failing. The more time it takes to vote, the more people will be discouraged. Lines are often longest in black and Latino communities, which have fewer resources to begin with and may be targeted by Republican politicians hoping to lower Democratic turnout.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

Voting in America is unnecessarily difficult, often by design. To paint non-voters as lazy, apathetic or morally culpable obscures the fact that we erect a wide range of barriers to keep people away from the polls.

A functioning democracy needs an engaged public to hold its elected officials accountable. That’s why efforts to expand the franchise and remove barriers to voting are so vital.

In Florida, for example, a referendum on the ballot this election could restore voting rights to 1.5 million ex-felons, including a full 21% of all black adults in the state.

Oregon has a new law that automatically registers people to vote when they interact with the DMV. It has contributed to a 4% increase in turnout between 2012 and 2016, the biggest jump in the country.

Many Americans don’t vote because our system is designed to keep them from doing so. That’s what we should be angry about — and what we need to change.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of “Corruption: American Political Films.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.