Op-Ed: Sorry, my fellow environmentalists, we have to build the delta tunnels

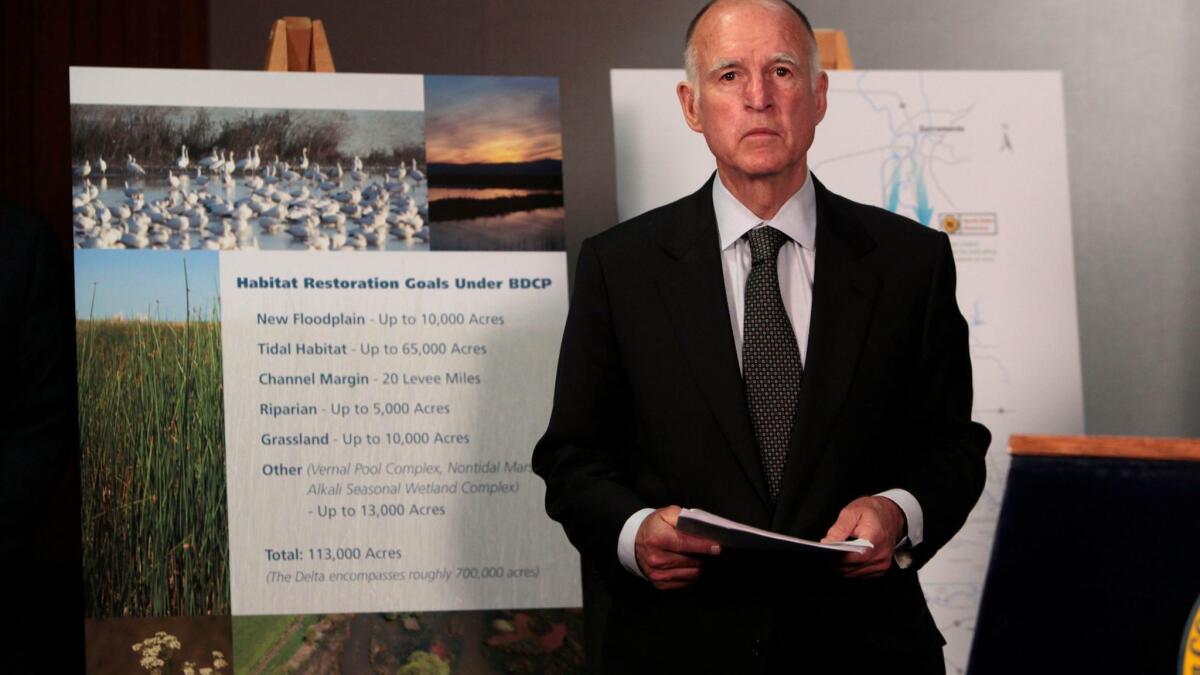

Environmentalists are adamant in their objections to moving water from Northern California south. They took a stand against the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta peripheral canal project in 1982, and they are against the delta tunnels project (the California WaterFix) now. I count myself an environmentalist but my position has long been less a stand than a crouch. I think the tunnels (or some form of them) are necessary but for years have preferred to let the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California take the heat for promoting them.

The problem with the crouch is that it’s become clear MWD, whose board votes on the project Tuesday, might fail. If it does, future planning for a third of Southern California’s water supply will be hard to distinguish from a disaster recovery strategy.

The tunnels are meant to be a joint project between cities and farms served by California’s federal and state north-south water works, with two of the biggest players being MWD, which delivers water to urban Southern California, and the massive agricultural Westlands Water District in Fresno and Kings counties. However, Westlands pulled out of the tunnels project recently, or at least balked at paying for it, and now the “no” campaign has turned its attention to the 26 Southern Californian cities whose water departments make up MWD, and who will be casting the last ballots in the tunnel fight.

The arguments against the tunnels are legion, and often contradictory. They offer no guarantee of more water but they’re a plot to steal more nonetheless; they cost too much; they’ll hurt imperiled native fish, or at least they won’t help them; they will intercept fresh Sacramento River water needed to dilute delta pollutants, and the most common objection: The tunnels are old hat in a new era of desalination, storm water capture, water main repair, recycling and conservation.

Southern California desperately needs both water conservation and reliable delta supplies.

Labeling the project a water grab ignores the legislative bargain behind the project, which ties delta supplies to reduced dependence on imports in Southern California. The same water quality rules that control the amount of exports now will be in force, and it is those rules, not the presence of tunnels, that determine how much water is taken.

As for cost, conservationists can’t argue that water is too cheap out of one side of their mouths, then complain out of the other that the estimated $2 to $5 a month the tunnels will cost the average household is onerous. Even if the costs were to rise sharply, Southern Californians might ask: What is expensive when safeguarding the third of its water supply that presently comes from the delta?

Without a doubt, cities and counties across the Southland need to diversify and modernize the way in which they source water, as well as conserve, conserve, conserve. Yet wade through the challenges enumerated in the fine print of the latest Sustainable Water Project Report out of UCLA and it’s also clear that far too many of these modernization plans are still conceptual. In 2012, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors failed to jump-start storm water capture because it would have required an average $70 annual parcel tax.

And what about the fish? Since the 1982 environmental “victory” over the peripheral canal, delta smelt, salmon, steelhead, sturgeon and chub have been steadily swimming toward extinction. When UC Davis biologist Peter Moyle, California’s presiding expert on delta native fish, came out in favor of the tunnels in August, it wasn’t because he thought the WaterFix was the best option for smelt and salmon. That would be dialing back delta water exports to pre-1980 levels. But given that Central Valley farming and 19 million Southern Californians aren’t going away anytime soon, and allowing for many uncertainties, Moyle concluded the tunnels are better for the fish than the status quo. (They could ease the reverse water flows, deadly for migrating fish, caused by the existing pumps in the South Delta.)

UC Davis engineer Jay Lund describes an intriguing alternative to the tunnels: a single “garden hose.” This smaller tunnel would throw Southern California a lifeline and it avoids the specter of a water grab that the large tunnels invoke. It would be cheaper and create less construction havoc. The shortcoming, according to MWD spokesmen, is that a single tunnel won’t provide the capacity to force gravity flow (so, more destructive pumping), nor will it make use of the massive amounts of runoff that a rational system must handle (and even store for drier days) as snow turns to rain in a warmer world.

Not every environmentalist has been crouching when it comes to the tunnels. Jonathan Parfrey of Climate Resolve wrote Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti last month reminding him that emergency measures had to be taken during the drought to keep saltwater from reaching the existing delta intakes that provide Southern California’s share of delta water. “Frankly,” he wrote, “it would be derelict to not protect California, our economy, environment and our people. We must build the damn tunnels.”

I’m with him. Southern California desperately needs both water conservation and reliable delta supplies. If we don’t build the tunnels — or tunnel, if it comes to that — we will lose a third of our water when, inevitably, drought, sea-level rise, an earthquake or levee failure renders the existing intakes and pumps useless. That’s not a state water plan. It’s a passive vote for catastrophe.

Emily Green chronicled the creation of two Southern California rain gardens in The Times and reported a 2015 series on the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta for KCET-TV. Her work on water and the environment is linked at www.chanceofrain.com.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.