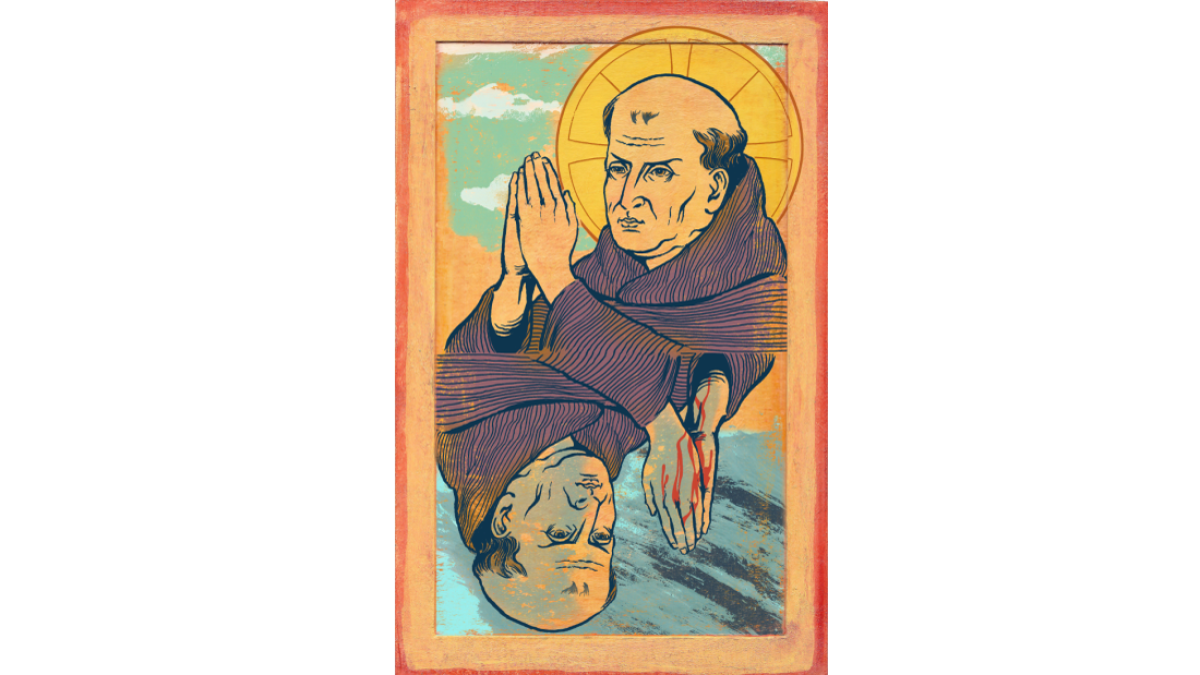

Op-Ed: Sainthood and Serra: His virtues outdistance his sins

- Share via

The outcries began as soon as Pope Francis announced that, after 80 years of formal consideration, Father Junipero Serra, founder of the California missions, was to be made a saint. The outrage isn’t new. It hews back to the accusation that Serra actively participated in “genocide,” a notion promoted by California Native American advocates such as Rupert and Jeannette Costo in the 1980s. For others it is bad enough that, to modern eyes, the mission system was oppressive.

But look closer. The majority of California’s Indians were never in the missions. The system didn’t enslave them (though it was a version of indentured servitude). And what killed most of them, in or out of the missions, was disease, lethal germs — which no Spaniard of Serra’s time had any clue about.

The “criminals” in this enterprise were not the Spanish, but the Americans. The indigenous population at the time of European contact (225,000) declined 33% (to 150,000) under Spanish and Mexican rule. Under American rule (from 1848 on), when most of the missions were in ruin, sold off or closed, the Indian population plummeted, to 30,000 in 1870 — an 80% drop. Either figure is tragic, but there is no mistaking who the major culprit was.

Sainthood and Serra: It’s an insult to Native Americans

Where is Serra in all this? And where the case for sainthood? Lost in the red herring of obvious, harmful effects of colonialism on the native population.

I spent 12 years researching Serra’s complex story. When I started, I assumed I would find an Indian tragedy that belonged on his doorstep. But I came to the conclusion that the missions were not places of unrelieved misery, and that in most things, Serra was exemplary.

In letters, mission and other archival documents, memoirs and the record the Roman Catholic Church amassed in investigating Serra for sainthood, I discovered Serra defending the Indians against Spanish comandantes and governors, both in Mexico and in California.

In Mexico, where he served 18 years before he came to California, someone poisoned his altar wine. The evidence indicates it wasn’t Indians who wanted him dead, but settler soldiers whom Serra had just rebuked for trying to wrest land from the natives, who were, in Serra’s phrase (he often used it, and it is telling) “in their own country.”

In California, in 1775, the Kumeyaay burned Mission San Diego to the ground and killed a priest close to Serra, along with two other Spaniards. In Carmel, where he got the news, Serra was deeply troubled. But in the end, he wrote the viceroy in Mexico City a startling letter: The nine Indians awaiting execution for the rebellion should be released.

“As to the killer,” Serra wrote, “let him live so that he can be saved, for that is the purpose of our coming here and its sole justification.” For me, that “sole” burns a hole in any argument that tars Serra with genocide. Time and again, Serra insisted the Spanish were not in California for gold or land, but the good of the indigenous people.

There is plenty of other evidence of Serra’s attitudes and his missionary dedication, his role, in the pope’s words, as the “evangelizer of the West.” On the road to Anaheim, when a war party of Acjachemen confronted him, he had only one Spanish soldier at his side. Serra came forward and blessed them all, to their astonishment. When he first saw naked Baja Indians, unlike other padres, he thought them “as in the garden before sin” rather than in a state of shame. Lifted out of the muddy floodwaters around La Conchita by the Chumash, whom the military feared, Serra was brought to tears, wondering how he could return their goodness. In a letter to the viceroy in Mexico, he insisted that if soldiers were unpunished for molesting Indian women and shooting Indians indiscriminately, “what business have we … in such a place?”

Yet Serra’s record is certainly not unblemished. What saint’s is? (See, for example, St. Paul and St. Augustine.) His fitness for sainthood especially gets hung up on the reprehensible practice of floggings in the missions, ordered for “spiritual improvement” over transgressions such as adultery and theft.

Why might Pope Francis overlook such flaws, pick Serra as a saint and waive the need for a second miracle (the first, according to the church, occurred in 1960 in St. Louis, for a nun at death’s door)?

Francis may recognize a kindred spirit. He and Serra were both academics who left the ivory tower. The pope shooed priests from the Colegio Maximo in Buenos Aires to labor in the barrios. Serra, a Mallorcan university theologian, threw it all away to serve Indians halfway around the world. Francis may see parallels between Serra and the Jesuit defense of the Guaranis of Paraguay (captured in the film “The Mission”). And just as Serra spoke truth to Spain’s power to win the Indians’ trust, Francis has pilloried the Vatican bureaucracy and titans of capitalism on behalf of the poor.

I have been asked what most surprised me in my research about Father Serra. The answer is, I liked him.

Saints are not perfect; they are revered because their goodness outdistances their sins. Serra faced government and settler demands for retributive justice against the Indians and put his life in jeopardy by insisting on radical mercy. I see his devotion to Native Californians as heartfelt, plain-spoken and borne out by continuous example.

When the pope canonizes Serra in September in Washington, I would like to be there. I would sit in the nosebleed seats, if necessary. No, I’d kneel.

Gregory Orfalea is the author of “Journey to the Sun: Junipero Serra’s Dream and the Founding of California.” He is writer-in-residence at Westmont College in Santa Barbara.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.