McManus: Applying the ‘ground game’

Outside the old red-brick City Hall in Manassas, Va., Dorothy Cummings was beaming. She had finally persuaded her son Charles to register to vote — and now she was marching him into the registrar’s office to make sure he got it done.

“Three votes in our family for Obama,” she said triumphantly.

Last Monday was the deadline for voter registration in Virginia, and the Obama campaign blanketed African American neighborhoods with phone calls and cards reminding people that time was running out.

PHOTOS: Six numbers to ignore from the presidential campaign

“We got two phone calls,” Cummings said.

Chalk up one small victory for the Democrats’ “ground game,” the often-unseen effort to register voters and make sure they get to the polls.

A hundred miles south, in the upscale suburbs of Richmond, Republicans are rolling out their own ground game.

COMMENTARY AND ANALYSIS: Obama vs. Romney

Pete Snyder, a former Internet marketing entrepreneur who’s running the effort for the state GOP, showed off a bank of brand-new telephones with buttons that allow volunteers to enter voters’ responses to questions — Do you plan to vote for Mitt Romney? Do you know where your polling place is? — directly into the party’s database.

“Do the Democrats have anything like this?” he asked rhetorically.

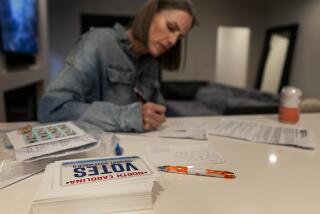

In fact, the Democrats do have a similar data system, just not as snazzy, but both parties also rely on older methods of cataloging information. “Not all our volunteers are comfortable with the technology,” an Obama organizer confessed, “so they still use paper tally sheets.”

Most media attention in a presidential campaign is lavished on the “air war,” the speeches, debates and television commercials that candidates use to get their messages out.

But in an election that appears balanced on a razor’s edge — in Virginia, the polls average almost exactly to a tie — a tiny difference in turnout could swing all 13 of the state’s electoral votes.

And that has led to a frenzied ground game in the state, with phone banks in dozens of storefront offices buzzing every evening and volunteers coming from nearby states where the race isn’t in doubt.

The two campaigns issue dueling statistics designed to show they’re ahead. Last week, the GOP announced that it had achieved almost 4.5 million “voter contacts” — conversations by phone or in person — in a state with only about 5 million voters. (Impossible to verify, the Democrats sniffed; besides, some of those were repeat conversations with the same voters.) The Democrats said they were ahead in voter registration, claiming that 88% of new registrants in Virginia were women, African American, Latino or under 30, all groups considered well-disposed toward Obama. (Impossible to verify, the Republicans sniffed; besides, the GOP is competing for those groups as well.)

Both sides are “microtargeting,” sending specific messages to particular groups. For Democrats, the biggest targets are women who might be worried about Romney’s positions on abortion and contraception. For Republicans, it’s veterans and defense industry employees who might be worried about Obama’s plans to cut the Pentagon budget.

There’s ethnic and religious targeting too. Democrats have a program aimed at African American barber shops and Latino bodegas, neighborhood gathering places that get frequent visits, posters and brochures. Republicans have aimed at evangelical churches; the Faith and Freedom Coalition, an outside group founded by former GOP official Ralph Reed, says it has identified nearly a million likely evangelical voters in the state and is sending all of them a voter guide.

“It’s not just church membership lists,” the group’s executive director, Gary Marx, told me. “There’s a lot of consumer data that helps. If someone has bought a Bible in a Christian bookstore in the past year, that makes them likely. If they’re married with kids. If they drive a Ford pickup truck. It all adds together.”

A Ford pickup? Yep. It turns out that driving a Ford F-150 is a pretty good sign that you might be a conservative — as opposed to the Subaru Outback, which Marx said is the country’s most liberal vehicle.

The story of this new science of electioneering is told in an absorbing new book, “The Victory Lab,” by journalist Sasha Issenberg. He recounts a 2006 experiment in Michigan by Yale political scientists who sent voters letters that listed all of their neighbors by name — and threatened to send another letter after election day revealing who had voted and who had not.

The “shaming” letter caused an astonishing 27% jump in turnout among voters who received it. But it also provoked angry protests from voters who felt that their privacy was being invaded.

Will the Obama and Romney campaigns try anything like that in Virginia? Absolutely not, officials in both campaigns told me. But they’ll come as close as they can without making people angry.

“There’s lots of research … that talking to people face to face makes them more likely to vote,” an Obama campaign official told me. “It helps to have their own neighbors talk with them. It helps to ask them when they plan to vote, and how they plan to get there; that way, they visualize themselves doing it. It helps to ask them to make a commitment.”

Does that sound a little Orwellian? Maybe. But it’s being done by both sides. And it’s encouraging, in an odd way, that it works best face to face, by volunteers from your own neighborhood. There’s something refreshingly low-tech about that.

Follow Doyle McManus on Twitter @DoyleMcManus

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.