What others see as Joe Biden’s mental slips, I see as the tricks of a master stutterer

- Share via

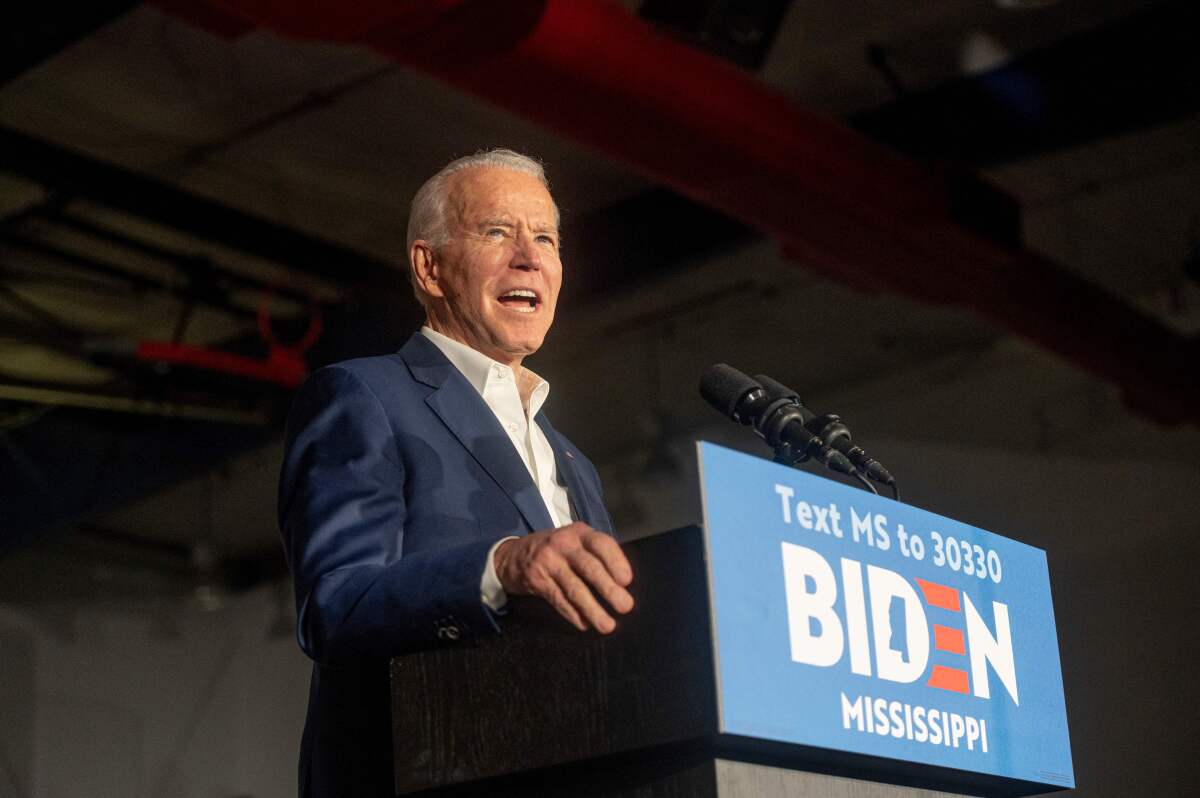

You don’t notice Joe Biden’s stutter when he’s speaking most of the time. He didn’t stutter during Sunday night’s debate, for example. But as a stutterer, I recognized the fingerprints of a master stutterer at work.

Seeing Biden on stage takes me back to my childhood. I’ve watched him for years and recognize the familiar tricks. Noticed him struggling with a phrase or name he’s uttered a million times before.

I’ve heard him use overly complicated or quirky phrasing and immediately recognized the method of a master stutterer: the almost savant-like ability to rephrase a thought or paragraph, on-the-fly, to avoid a problematic word or syllable.

I’ve listened to his critics and heard echoes of my past. He’s senile, they insist. He forgot Obama’s name. He’s mentally defective. Dementia. But I know better.

At a campaign stop on March 5, Biden “forgot” Obama’s name, identifying him simply as “the last guy.” At other events he’s said, “President my boss.” Some see this as evidence of a man losing his mental faculties. I see the familiar trick of calling a last-second audible for an easier syllable or phrase, the in-the-moment wordplay stutterers use to navigate their speech.

Stuttering is fickle. A word might come naturally the first million times, then get stuck without warning. So we make substitutions. Sometimes it’s nicknames. Sometimes it’s slang that sounds awkward or out-of-place, like Biden uses.

I started stuttering when I was 7. First a little. Then a lot. I hoped it would go away. It never really did, though I didn’t let it stop me from having a full life. I speak in public all the time now. I enjoy it.

Growing up is hard. Stuttering makes it harder. You can’t do what other kids do, and they don’t understand why. They’d ask me to say things, knowing I couldn’t. Sometimes it was to my face, other times when they didn’t know I could hear them.

People didn’t always mean harm. Yes, I have seen “A Fish Called Wanda.” Yes, Michael Palin’s character stuttered, too. And “My Cousin Vinny,” when the free lawyer stuttered so badly he couldn’t get through an opening argument? Hilarious! Thank God I’m not that bad, right?

Those moments stung. But they didn’t hurt as much as the good intentions, the people trying to help, that reminded me that I was incomplete. Sometimes teachers would skip over me in class so I wouldn’t have to try to speak. Sometimes I had things to say, ideas to share, jokes to tell. They became my secrets.

In fifth grade, I auditioned for the lead role in the school play (quite well, I might add), only to be cast as a nonspeaking extra. Better that than stumble over a word in front of 300 kids, they explained. Part of me was relieved. The other part was sad to see another door close. Another thing I could never do, etched onto my permanent record.

As stutterers do, I found ways to manage it. Speech therapy helped a little. The real method was word craft similar to what Biden does, the self-trained ability to re-architect language in real time to avoid a word or syllable you know will stop you cold.

In high school I discovered the art of performance — singing and dancing. These short-circuited the stuttering pattern. When I sang I could be loud. When I acted on stage, I could be confident. Strong. Clear. I could be someone else.

People would find me after performances and congratulate me on finally overcoming the stutter. I would smile, but I knew the truth. It was still there, lingering, waiting.

People who have never stuttered may look at Biden and see a man who can’t say simple words, remember simple names, or use the obvious phrase in every occasion. While they see a mental defect, I see a man who has survived decades on the political stage, still working to overcome a disability he’s carried his whole life.

Biden is an example that doors don’t have to stay closed. Proof that people can manage disabilities and excel at the very things others thought they could never do.

There are would-be Joe Bidens everywhere. Looking down. Avoiding attention. Afraid to raise their hands in class. He shows that they don’t have to be afraid to speak up.

Dan Roche is a technology consultant in the Washington, D.C., area. Twitter: @danrochewrites

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.