Coming to grips with the checkered history of John Muir — and the conservation movement

- Share via

Memorials to revered naturalist John Muir are strewn throughout the United States — and far beyond. In California alone, 18 public schools are named after him, five of them in Los Angeles County. Not to mention a redwood forest and the 217-mile trail that begins in Yosemite Valley, a place he wrote about with rapture. There are lodges and a rock and an inlet and, oddly, highways. The honors stretch into Canada, across the sea to Scotland and even into outer space, where a tiny planet was dubbed Johnmuir in 2006.

What could be unlovable about a man who directly helped preserve Yosemite and Sequoia as parks, who co-founded the Sierra Club and is considered the father of the national parks system because of the admiration for wilderness that he inspired?

The answer: his overt racism toward Black people and Native Americans, including the Miwok tribe that inhabited Yosemite Valley long before the arrival of the white men who expelled them. Muir’s racism hasn’t exactly been a secret, but it’s not well known, either. Hey, he’s the guy we put on our state’s quarter in 2005, not a man famous for hateful viewpoints.

That is, until this week, when the Sierra Club openly acknowledged the truth about Muir. And it didn’t stop there; the environmentalist organization also called out the white supremacists and eugenicists who were prominent early members of the group, and reminded us that people of color were at times excluded from the club.

Though the Sierra Club’s announcement didn’t go into detail, it’s known that Muir supported ejecting Native Americans from their lands to make way for people-free open spaces. He described the Miwok people, most of whom had been killed or driven from Yosemite by the time he arrived in 1868, in the ugliest of terms, writing that they were “dirty,” “altogether hideous” and “seem to have no right place in the landscape.”

This land may have been made for you and me, but to Muir and other early conservationists, “you and me” meant the class of white gentlemen who made occasional forays to what Muir saw as the untouched beauty of wilderness.

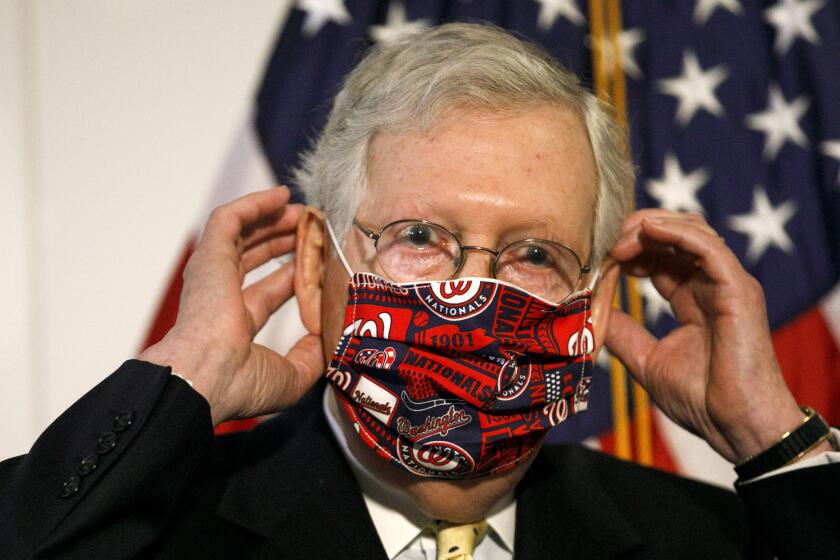

Editorial: Mitch McConnell is twiddling his thumbs as American workers head toward a financial cliff

The current recession would be much worse if Congress hadn’t provided higher cash benefits to millions of newly unemployed Americans.

Muir actually misunderstood the “untouched” part as well. The open meadows he admired that afforded broad views of the geological splendors of Yosemite weren’t the hand of nature; they were the result of strategic fires set by the Miwok to prevent undergrowth and catastrophic forest fires. Forty years after the Miwok were gone, so were the meadows.

Of Black people, Muir infamously wrote, “One energetic white man, working with a will, would easily pick as much cotton as half a dozen Sambos and Sallies.”

This hateful viewpoint wasn’t confined to the early leadership of the Sierra Club. It’s long past time for the conservation movement in general to confront the ways in which its early history was entwined with the eugenics movement, the idea being to protect the finest of nature along with what these supremacists saw as the finest of humankind.

Among others was Gifford Pinchot, head of the U.S. Forest Service under President Theodore Roosevelt (who himself held racist viewpoints). Pinchot saw land preservation as naturally linked to continued dominance by white people. A conservation report written under his authority called for forced sterilization or prohibition of marriage for criminals and other elements seen as undesirable. “If our nation cares to make any provision for its grandchildren and its grandchildren’s grandchildren, this provision must include conservation in all its branches — but above all, the conservation of the racial stock itself.”

Good for the Sierra Club for beginning the process, openly admitting and rejecting the unacceptable aspects of its beginnings and vowing to remake itself, including bringing on racially and ethnically diverse leadership.

This doesn’t have to mean stripping Muir’s name from the dozens of sites that honor him, a man who felt more affinity for bears than for people regardless of their skin color. It’s far more important to take meaningful steps toward cultivating wider interest in and access to open lands. The National Park Service, to its credit, has worked in recent years to bring more diverse groups of visitors to the parks.

As for Muir, he eventually came to learn more about Native Americans, to openly admire them and to decry cruel treatment of them. He was flawed in a terrible way, he showed himself capable of learning at least somewhat, and he left a rich legacy, an incredible trove of natural beauty. Now it’s time to make sure it was made for all of us.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.