Fifty-five summers have gone by since the Watts rebellion. How far have we traveled?

- Share via

In the summer of 1965, my birthday cake was stuck at a bakery across town. My mother couldn’t get to it because Watts was on fire, which sent surrounding cities, like ours in the South Bay, into lockdown.

No way could she have known when she placed the order for my fifth birthday that a white highway patrol officer would soon pull over a young Black man for reckless driving and, in the ensuing chaos, arrest him, his brother and his mother. It was a sequence of events that played poorly in a community already bristling at overcrowded housing, low-wage jobs and routine incidents of police brutality.

In those six days of rebellion — which some might call a fed-up-rising — residents clashed not only with police but also the National Guard. In the end, 34 people lay dead, more than 1,000 had been injured, and tens of millions of dollars in property was gutted.

That smoke lingers, and the people periodically erupt in outrage, as when officers were acquitted in 1992 following the brutal beating of Rodney King, or when George Floyd died after a cop knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes while he lay face down and handcuffed.

As the New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow wrote recently, “The lulls you experience between explosive revolts of the oppressed should never be mistaken as harmony. They should be taken as rest breaks.”

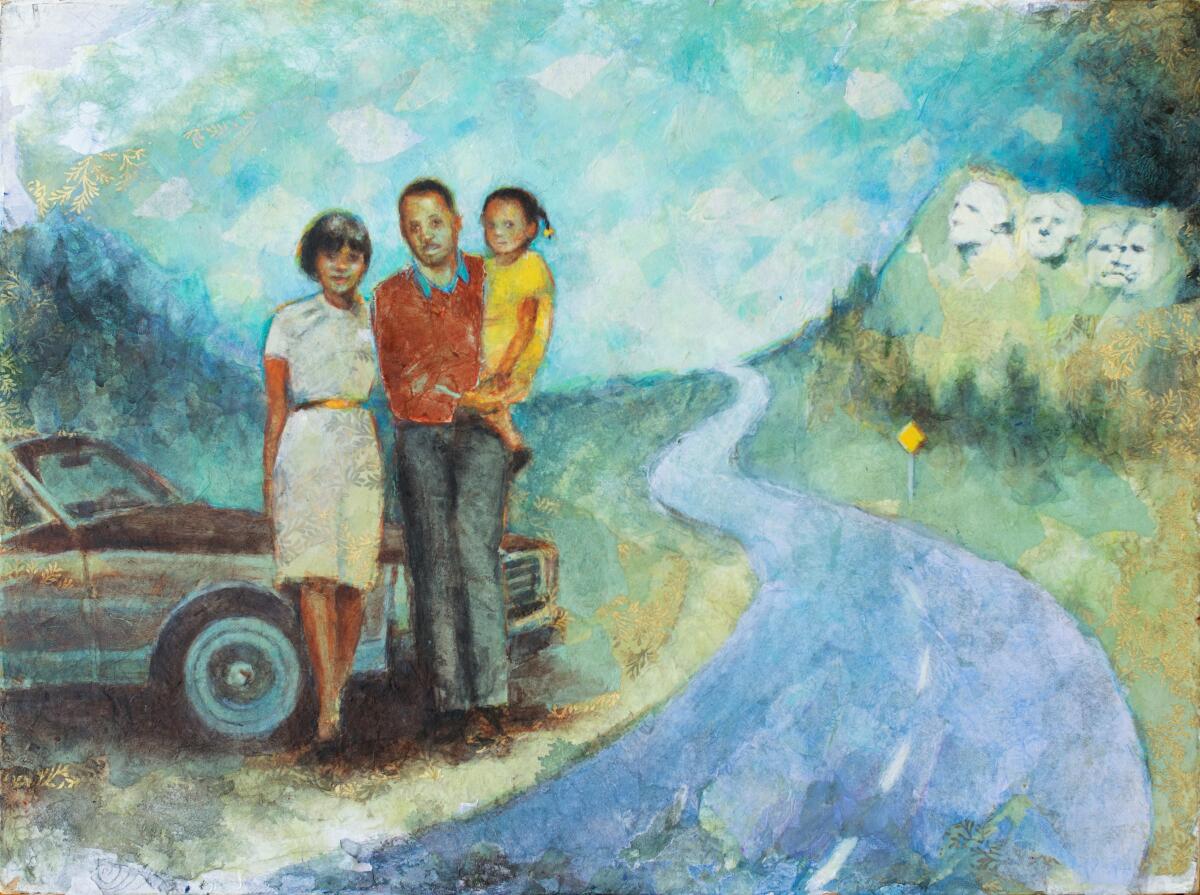

In the summers of the 1960s and early 1970s, my family could only hope for the best when driving while Black from Los Angeles to New York every other year. We went to reconnect with our East Coast kin.

To guide us, my mother ordered TripTiks from the American Automobile Assn., small, spiral-bound books that outlined the best path. My sense is that my parents asked for directions that expressly avoided the South, out of concern that we might get pulled over by racist highway patrolmen during the turbulent civil rights era.

In a time before major interstate highways, we connected to Route 66 and kept it moving along two-lane highways dotted with bad diners and dimly lighted motels. To pass the time, my mother read my father and me novels, such as “The Grapes of Wrath.” The AAA TripTiks highlighted points of interest along the way, such as Native communities or petroglyphs, but we flew by them all to make “good time.”

Once we were safely in New York, our people descended on us in my grandmother’s Harlem kitchen. Over the next couple of weeks, we visited family around the tri-state area and in New Castle, Del., and binged on a buffet of delights at Coney Island.

Only on the way back did we slow down to sightsee. We might cruise the pulse of Chicago’s Michigan Avenue or down a two-laner through Davenport, Iowa, stalks of corn swaying as if to the tune of “for amber waves of grain.”

We wound our way up the Black Hills of South Dakota to regard the 60-foot faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln blast-sculpted into granite. We strolled around charming Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and heard the church bells peel at noon.

When we entered a restaurant, hotel or curio shop, I secretly watched to see how people received us as a Black family. I can’t remember coming across anyone who was unwelcoming.

At the same time, these were the same years when a president, a presidential hopeful — John and Robert Kennedy — along with three civil rights leaders, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, were assassinated.

The tranquil beauty of the United States passing by my window over those summers seemed out of sync with our country’s history of violent bloodshed. I began to perceive the image of America as a glossy brochure for a house, where the best features are well-lighted and captured with a wide lens while flaws, such as lead water, termites and a roof about to cave, were cropped out.

Of all the places we toured, Mt. Rushmore made the deepest impression. At the time, I was ignorant that it was built on stolen Indigenous land by a sculptor with ties to the Ku Klux Klan. I just remember gazing up at those carved faces, particularly Lincoln’s, farthest to the right, and noting that the pinch in his brow barely hinted at the pressure he faced watching the U.S. become engulfed in a civil war over slavery.

Though Lincoln tried to warn us that a house divided against itself cannot stand, our country has yet to mend its cracked foundation. Too many continue to hold the American brochure aloft, while stubbornly refusing to address the pressing repairs needed to fix the racism, inequality and police brutality.

Recently, I heard a NPR interview with the Rev. Raphael Warnock, the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist, Martin Luther King Jr.’s old church in Atlanta. He said that the current moment is not about burning ourselves out trying to squash all racial hate.

“I just want to make sure that our city and our state and our country is not too busy to love,” he said. “And justice is what love looks like in public.”

As the 55th anniversary of those fateful, fiery days in Watts approaches, there’s no AAA TripTik we can follow to show us a way forward. But I think James Baldwin sagely pointed toward the North Star when he observed: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Pamela K. Johnson is a writer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles. @pamelasez

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.