Op-Ed: Here’s how the GOP is likely to respond to defeat in November

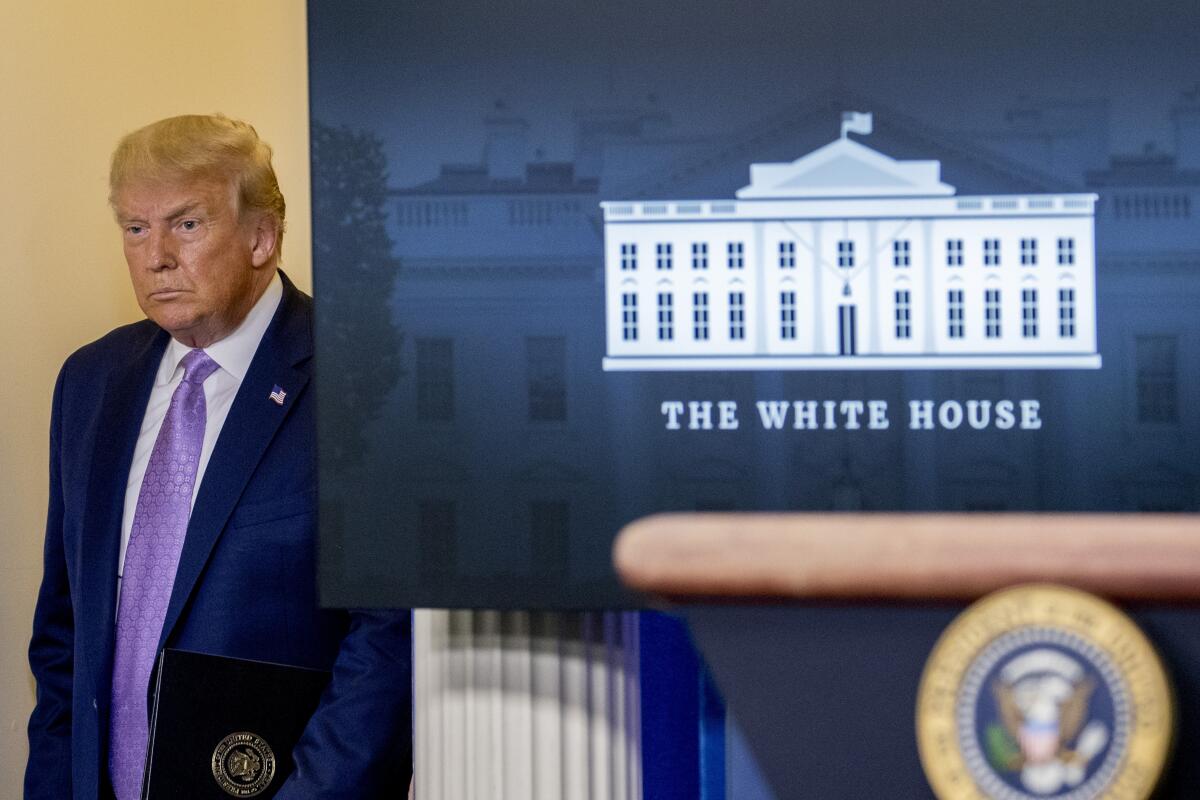

The prospects for Donald Trump’s reelection are looking challenging at best, and it’s not too early to consider what a Republican Party without Trump in the White House would look like.

A lot depends on how the party responds to defeat. This is where the Republicans and Democrats show a great deal of difference.

In my research on the Democratic Party after the 2016 presidential loss to Trump, I found that party leaders and activists viewed Hillary Clinton’s electoral college loss — even though she won the popular vote by 3 million votes — as a moment to reconsider a lot of what they believed about politics. They were willing to explore considerable changes to how they nominated candidates and what sorts of candidates would broaden their appeal. Seen in this light, Joe Biden’s successful nomination bid, despite previous failed attempts, is not terribly surprising.

Would the Republicans view a Trump loss as cause to do the same?

In his book “The Losing Parties,” political scientist Phillip Klinkner examines how party insiders reacted to presidential losses between 1956 and 1993. As Klinkner notes, the parties have behaved differently after experiencing a loss.

Democrats have often been open to substantial reforms of their nomination processes and are willing to re-examine the kinds of candidates they put forward. A narrow loss to Richard Nixon in 1968 produced the most substantial reforms to party nominations any American party has seen in its history.

Jimmy Carter’s failed reelection bid in 1980 sparked concerns that the party had become too open to presidential candidates without ties to Washington (even though he succeeded in winning the presidency in 1976 as an outsider) and that party insiders should be given a stronger role in the nomination process.

Many Democratic losses over the years have produced criticism from centrist leaders within the party that movement toward more inclusiveness and a stronger civil rights agenda pushes the party toward non-electability. Even as Democrats came increasingly to see inclusiveness as their core mission, they were willing to deemphasize that mission after a loss if they thought it would increase their chances of governing.

After the Democrats’ huge loss in 1984, a Southern state party chair said, “The perception is that we are the party that can’t say no, that caters to special interests and that does not have the interests of the middle class at heart.” The Democrats developed the Super Tuesday primaries after that loss in part to strengthen the voices of the Southern white wing of the party.

By contrast, Republicans are far less likely to rethink their core ideology, whether that involves reduced government regulations or an increased role for fundamentalist Christian beliefs in public policy or anything else. Instead, as Klinkner notes, they have tended to respond to losses with nuts-and-bolts reforms, developing innovative advertising practices and reassessing which parts of the country to prioritize in campaigns.

These kinds of changes are certainly important. For example, the GOP decision after Richard Nixon’s narrow 1960 loss to John F. Kennedy to reallocate resources from Northern cities to Southern states would have important long-term consequences. But there’s rarely a rethinking of the types of candidates the party believes can win office.

Importantly, there are real limits today on what the Republican Party could do to change its priorities even if its leaders wanted to. After Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss to Barack Obama, leaders within the Republican National Committee produced a famous “post-mortem” report calling for the party to embrace immigration reform and to nominate candidates whose message wouldn’t alienate women, African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans and gay voters. The party’s rank-and-file basically ignored those recommendations in 2016. Their support for Trump, and the party’s inability to prevent his nomination, was about as complete a repudiation of that post-2012 report as one could have dreamed up.

If Trump loses in November, the GOP may find itself in a worse position than in 2012. The party would have then lost the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections. Given the increasing diversity of the electorate, some in the party would want to seek ways to distance the party from the nativism and bigotry that has been at the core of Trump’s appeals.

But that faction would find itself opposed by a Trumpist wing of the party that sees white identity appeals as the key to the party’s success, and has been happy to tie its fate to Trump himself. It is notable how many prominent younger Republican leaders, including former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley, Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), Gov. Kristi Noem of South Dakota, and others, have repeatedly and very publicly lavished praise on Trump even as his popularity sinks.

Even if Biden wins, Trump is unlikely to go quietly. He is already trying to delegitimize a potential Biden victory, claiming that mail-in voting is rife with fraud (it’s not), suggesting the election needs to be postponed, and trying to limit funds for the U.S. Postal Service so that it might not be able to process all mailed ballots in time. He would probably spend much of a Biden presidency railing against the election, and possibly even setting the stage for his own 2024 comeback.

The truth is, a sizable portion of Republican elected officials, political commentators and Trump voters have a great deal invested in the party’s current identity. With Trump not exiting the stage, few GOP leaders would press to conduct a “post-mortem” of the 2020 election. In that way, the party is very different from the one that lost in 2012.

Seth Masket is a professor of political science and director of the Center on American Politics at the University of Denver. He is the author of the forthcoming book “Learning From Loss: The Democrats, 2016-2020.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.