Editorial: California schools are off to a better start. But problems persist

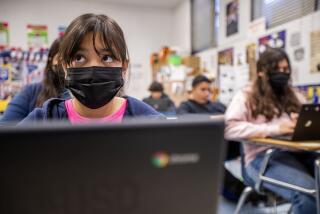

It’s not last spring’s remote education, thank goodness. For the new school year in California, nearly every student has a computer of some kind and broadband access to online classes and instructional resources. There are actual grades for academic performance. And the state has set minimums for the number of hours teachers must provide instruction, some of which has to involve real-time interaction between teachers and students.

Almost none of these things were happening during the last three months of the past school year. A lot of students might as well have taken the last few months of the year off. When teachers weren’t fully engaged, students spent their time filling out worksheets, interacting directly with their teachers as little as once every couple of weeks. On the other hand, students with computers, committed teachers and parents who could afford to help them fared much better.

Of course, many teachers didn’t know how to do video lessons, lacked equipment and had their own children to care for. Families weren’t prepared, either. The COVID-19 lockdown hit nearly everyone with immediate ferocity.

That claim can’t be made for this fall. There’s been time to prepare. To their credit, Los Angeles Unified schools, along with many others in the state, have stepped up in a whole range of ways, including providing childcare for teachers’ children. There are real class schedules. And for elementary school students, specific times have been set aside for English and math lessons.

Is American life destined to imitate our dystopian movies, or does Biden offer a path back to normalcy?

Still, no one should fool themselves into thinking that L.A. students are getting the kind of education that they would if this were a conventional school year. For one thing, teachers are not required to work as many hours — six a day instead of the previous eight. Other large school districts in California have agreements with teachers that call for the usual eight hours or something very close.

Add to this another concern: L.A. Unified appears to be defining student attendance so broadly, it might not mean that students are actually present and learning. If students appear during an online lesson at all, even if very briefly, or if they contact their teacher during the day, or turn in work without actually logging in during class, they can be counted as present. The district says it’s meeting the state’s requirements, but that shouldn’t matter. This is not what most parents, teachers or the public think of as attending school.

As for teachers’ shorter work day, L.A. school officials say their agreement actually requires more direct student-teacher interaction during the day, even if the total number of work hours is significantly shorter.

But adding more direct lesson time isn’t the issue. There are just so many hours in a day that students can stare into a computer screen before their eyes glaze over and they stop absorbing new material.

Critics of the district’s teacher agreement, including the reform group Parent Revolution, point out that the Elk Grove schools set aside far more time for parent-teacher communication, an important element when parents bear so much responsibility for making this work. Considerably more time could be spent on virtual office hours, during which students work independently but can call on their teachers if they get stuck.

Of course, just as during the spring, there will be many committed teachers devoting time far above the call of duty so that their students will learn as much as possible. What’s most important, now that there are at least some reasonable minimums for instructional time, is not how many hours the teachers work, but the quality of those hours. Are they engaging students during the limited classroom sessions or are they spending too much of that precious time having students fill out worksheets? Do they know how to reach out effectively through online platforms?

Supervision of those classes is crucial to making online learning more successful than it was last spring. The problem is that under L.A. Unified’s agreement with the union, teachers must be given advance notice when their class is going to be observed. Principals would get a more realistic idea of what’s going on if they could pop in randomly.

Until on-campus instruction can begin safely, students, teachers and parents will need to make the best of a less-than-ideal situation. For now, L.A. Unified should be pouring resources into having principals and other administrators check in on classes often and giving teachers support and guidance. It should set up easy pathways for parents to raise concerns and get timely responses; parents already are complaining about long waits on hold for the hotline.

And students should not be counted as being in class for the day unless they truly are in class for the day.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.