Who dropped the ball on extra school time for LAUSD? Just about everyone.

- Share via

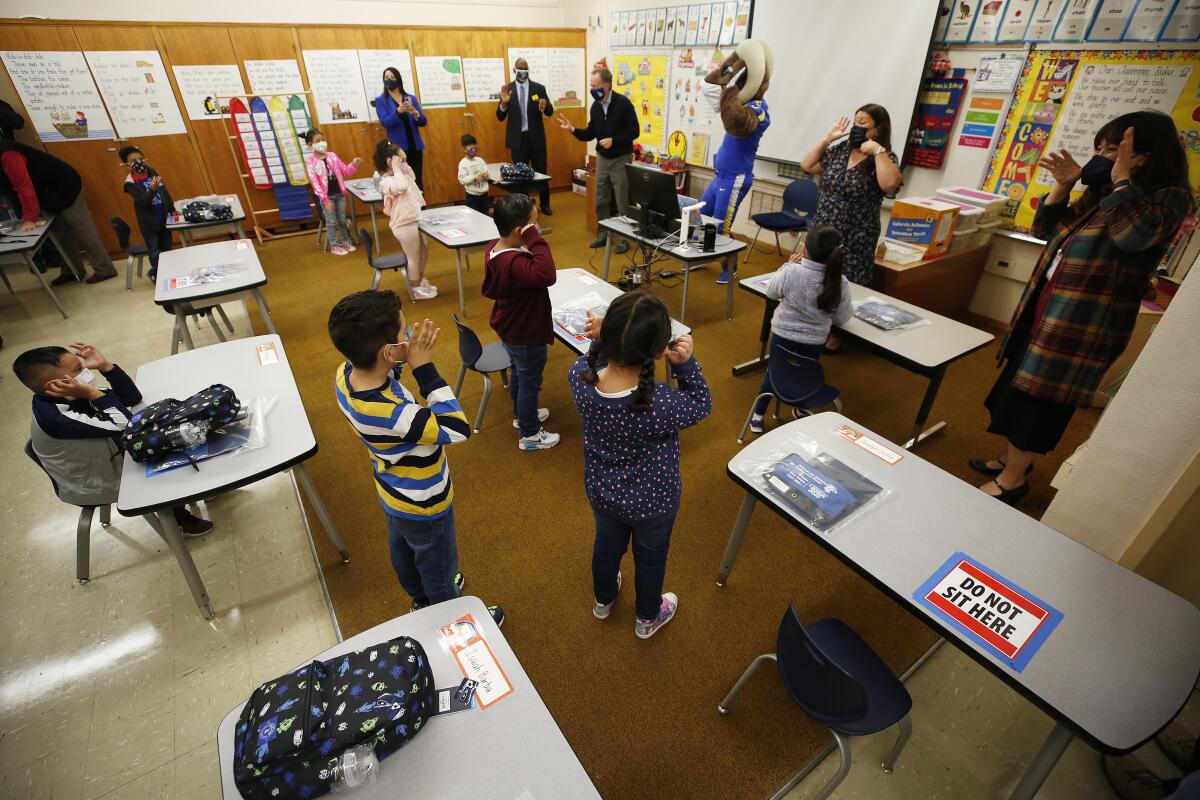

We get it. Los Angeles teachers have been through the grinder for more than a year. Many of them went far beyond the minimum to try to help students learn during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for much of that time, those with kids of their own had parenting duties to fulfill too. No wonder they didn’t feel up for the two extra weeks of school that the district sought to add next academic year, even though they were offered extra pay.

Meanwhile, some haphazard polling of parents indicated that the majority wanted the extra two weeks, but they didn’t want to see family vacation plans interrupted.

Pushed back from both sides, the Los Angeles Unified school board blinked, deciding Tuesday not to make the change. In none of this did the needs of the students take first priority. Or any priority, it would seem.

There is widespread agreement that online education has been a pale substitute for classroom learning in most cases. A January report on California schools by the think tank Policy Analysis for California Education found an overall learning loss in both reading and math during the pandemic, especially among disadvantaged students and those who are not yet fully fluent in English.

And it didn’t help matters that L.A. Unified students got less face-to-face instructional time during the pandemic than students in other large California school districts, under the agreement the district negotiated with United Teachers Los Angeles.

Too many students have fallen behind. This was the time for a major push on academics. And research indicates that extended school time can make a real difference in student outcomes.

The fatigue of teachers matters too, of course. But the district is making summer school voluntary for both teachers and students. Even if the new school year were to start a week earlier, as the district proposed, teachers would have had several weeks to rest up if they skipped the summer session. That’s not an option many people get in their jobs. And families that wanted vacation time rather than summer school would have had ample time off, minus just one week.

The district still plans to offer extra learning time to students in the coming year, but without its regular credentialed teachers and in ways not yet defined. That’s not a recipe for success. L.A. Unified could try offering intensive tutoring, which research has found to be even more effective than extended school time, but it would be difficult to carry that off across a huge student population like this one.

Summer school is another worry. The district is thousands of teachers short of what it needs for the academic portion of the days, which means substitute teachers or others will be brought in to help. Many of them might be very good, but this isn’t a reliable way to give students the academic boost they need after so many difficult months.

Some board members complain that although outgoing Supt. Austin Beutner announced plans a while ago to try to reverse learning loss through summer school and an extended 2021-22 school year, he didn’t follow up with the necessary outreach to bring parents and teachers on board. Beutner says he’s engaged in consistent and extensive communication with teachers and parents on the subject for months.

In either case, the board should have tried harder to get an agreement to extend the school year. But in the face of opposition from two unions — the principals’ union joined with UTLA to oppose the longer calendar — its chances were poor without the support it needed from the state. When Gov. Gavin Newsom gave schools considerably more dollars to spend, he supported the idea of using them to fund extended school calendars but never pressed the matter. And the Legislature failed to mandate a longer school year for next year, which would have been especially helpful for large school districts with many disadvantaged students.

In the end, despite the extra money supplied and the anguish expressed about learning loss among disadvantaged students, no one would do what it took to provide what those kids really need. Summer school is unlikely to be the robust, teacher-led program necessary to give kids a leg up on next year. Neither the school day nor school year will be longer next year in the ways that matter. There still is no formal academic recovery plan. If we despair in the future about the students who never got fully back on track in the years after the pandemic, we’ll know a major reason why.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.