Remember the Freedom Riders — and how police and the FBI colluded in the attacks against them

- Share via

In the spring of 1961, a group of Black and white civil rights activists set off on a trip through the American South, aiming to test recent federal court rulings banning racial discrimination in interstate travel. They sat where they pleased on the buses they rode. They entered the waiting rooms in the terminals, sought service in the depot restaurants and used the bathrooms.

Mundane as that may sound today, an article on these pages a few days ago described the vicious welcome the first Freedom Riders received. The author, a 12-year-old girl at the time, watched as one of the two buses carrying the activists from Atlanta arrived on May 14 in Anniston, Ala. An angry mob of Ku Klux Klansmen forced the Greyhound bus off the road, firebombed it and beat the escaping passengers bloody.

Yet, shocking as those events were 60 years ago, I’m even more disturbed by what happened to the second bus — the Trailways bus that left Atlanta just an hour later that day with seven Freedom Riders aboard headed to Birmingham, Ala. The story of that second bus resonates troublingly today, as Americans focus once again on this country’s history of systemic racism and on the treatment of African Americans by law enforcement.

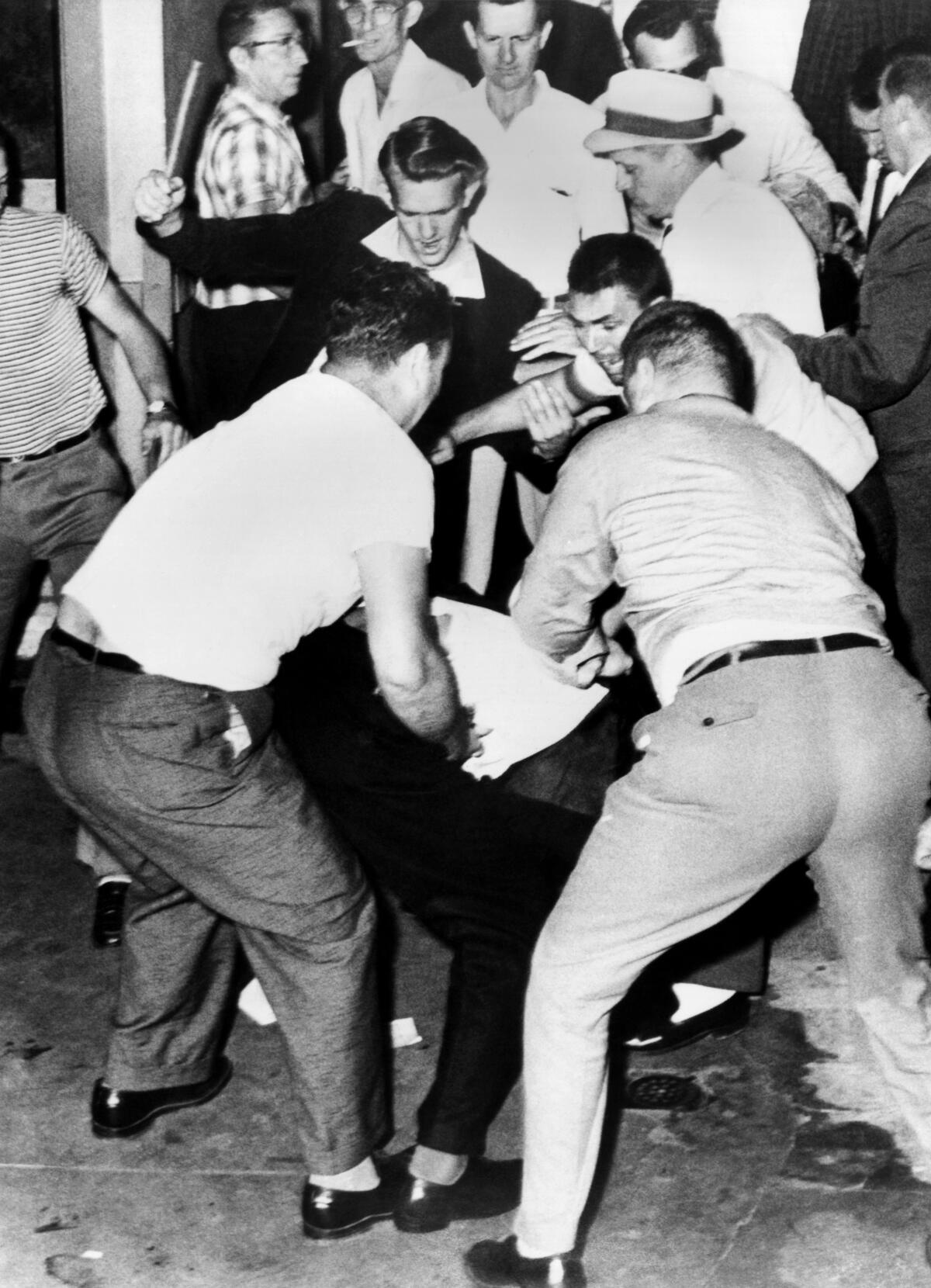

On the face of it, the riders on the two buses met similar fates. The Trailways bus got to Birmingham, and like the Greyhound bus at Anniston it was met by a mob of white men armed with pipes, baseball bats and chains. Brutal beatings left the Freedom Riders and some bystanders bloody, groggy and battered. One needed 53 stitches. Nine were hospitalized.

But what the riders didn’t know was that the plan to meet them — and stop them — had not been hatched by the KKK alone, but in conjunction with the Birmingham Police Department. Acting on the orders of Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s 63-year-old, ultra-segregationist public safety commissioner, police officials had held secret meetings with the leaders of the Eastview klavern of the Klan. Not only did they hand over the Freedom Riders’ itinerary, but they promised the Klansmen 15 to 20 minutes to do what they would at the bus station before police arrived.

“I don’t give a damn if you beat them, bomb them, murder or kill them,” said Det. Sgt. Tom Cook, who handled “racial matters” for the force.

The collusion of the Birmingham police is reprehensible, but perhaps not so surprising. As many histories of the era point out, the department under Connor was notorious for its antipathy to integrationists and “out-of-town meddlers.” Two years later, its fire hoses and police dogs became worldwide symbols of violent Southern resistance to racial justice.

But what is as troubling is that J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI were also aware of the plan to turn a blind eye to the violence.

The FBI had an informant in the Eastview klavern. Gary Thomas Rowe was a 28-year-old machinist who had dropped out of school in the eighth grade but always wanted to be a law enforcement officer. Rowe, a confidant of the Klan leaders, was aware of the scheme to allow the extra 15 or 20 minutes — in fact, he helped organize it — and he contacted his handlers at the bureau.

He told the FBI of the planned attack. He described the conspiracy with police. His report was forwarded to headquarters in Washington.

You’d think that would have stopped the attack in its tracks. Hoover and the FBI were responsible for upholding federal law. Atty. Gen. Robert F. Kennedy had promised in a speech just a week earlier that his brother’s administration would not “stand aloof” but would enforce civil rights statutes.

FBI officials could have stopped the violence, or they could at least have warned the Freedom Riders.

But they opted not to. Later, on the defensive, FBI officials fell back on the excuse that the bureau’s role in local law enforcement matters was limited to intelligence gathering. But in truth, Hoover himself always viewed the civil rights movement as communist-inspired and repeatedly sought to undermine it.

So the attack went forward. Rowe, the FBI informant, was an active participant. Connor lied to the news media when he said the police were slow to show up because it was Mother’s Day and officers were home with their families.

The role of the police and the FBI stayed secret until 14 years later, when Rowe discussed it in testimony before Congress — and it has mostly been forgotten since then.

Contributor: As a 12-year-old, I defied the KKK to comfort Freedom Riders injured in a firebombing

Sixty years ago, a preteen white girl in Alabama tended to Freedom Riders after their bus was firebombed. Her life would never be the same.

“In hindsight,” reads the chillingly blasé language of a Department of Justice report on the matter, “it is indeed unfortunate that the bureau did not take additional action to prevent the violence, such as notifying the Attorney General or the U.S. Marshall’s Service, who might have been able to do something.”

Yes, it is unfortunate.

These are old stories now. The Jim Crow South is part of history. But after the George Floyd protests, as the U.S. reckons again with policing and racial justice, the events of May 1961 are worth remembering.

And one of their lessons is this: It’s not enough to celebrate the heroism of the Freedom Riders, or to condemn the depravity and violence of the white supremacists who came to meet them.

Government was complicit. The police were racist. The FBI was, in the most charitable analysis, dangerously disengaged; Americans were mostly complacent. This is part of what systemic racism is about.

The Freedom Riders set out to awaken the slumbering conscience of the country.

Six decades later, undeniable progress has been made, but we’re still waking up.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.