Kyle Rittenhouse was just acquitted. The path toward justice in America is a rocky one

- Share via

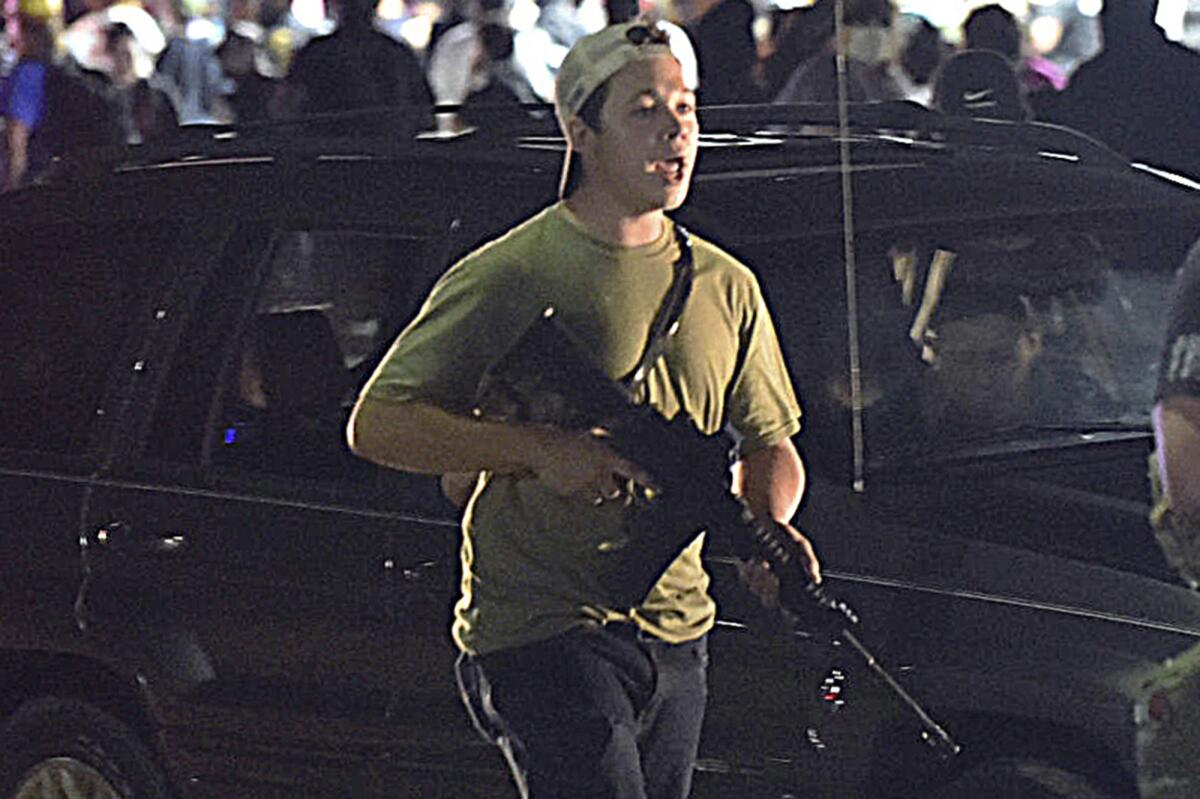

The acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse on Friday on charges stemming from his shooting two people dead and wounding a third during a violent protest in Kenosha, Wis., on Aug. 25 of last year is a reminder that the nation’s pathway through its wrenching debate over race, policing and identity — as well as gun ownership and the laws protecting vigilantism — is neither straight, clear nor short.

Inside the courtroom, Rittenhouse’s trial was not about race. All three men he shot were white, as is he. Nor was it directly about policing, because even though he was an enthusiastic follower of law enforcement, he was not a police officer. The case was strictly focused, as it should have been, on whether he believed that he was acting in self-defense when he fired the deadly shots.

Under Wisconsin law, this jury said, he was.

Kyle Rittenhouse is found not guilty of all charges in the killing of two people during a protest last year in Kenosha, Wis.

The protest to which the then-17-year-old Rittenhouse traveled with a medic kit (picking up a semiautomatic AR-15-style rifle from a friend along the way) from his nearby home in Illinois was over the police shooting two days earlier of Jacob Blake, a Black man shot seven times in the back and side by a white officer — one of many instances of white police unnecessarily shooting — and sometimes killing — Black men. Such killings have been part of the American landscape for centuries, but they have drawn increasing scrutiny in the last decade, with the reaction more contentious, especially amid the unsettling COVID-19 pandemic, and especially following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020.

The Kenosha protest was part of what makes up a second, continuing trial, not just of Rittenhouse or the killers of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and many others, but of contending factions — liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats, gun advocates and gun opponents — and the ability of democracy and our political and legal systems to accommodate and mediate the debate of how Americans view themselves and their society.

Are we a nation that has largely expunged inequity and racism, or one unceasingly and increasingly plagued by those ills? Have we made ourselves safer from harm, exploitation and tyranny by arming ourselves, or are we instead more vulnerable than ever precisely because we have so many guns? Do police hurt us, or perhaps exacerbate our already divided society because they protect one part of the population and hurt another?

Kenosha County Circuit Judge Bruce Schroeder may not like news coverage of the Kyle Rittenhouse trial in his courtroom, but banning reporters and televised coverage is exactly the wrong solution.

Convictions like Chauvin’s earlier this year and acquittals like Rittenhouse’s are taken as victories or defeats for the various sides in that larger debate, but court verdicts are poor stand-ins. The role of the criminal trial is to seek truth while protecting defendants from overreaching government prosecutors, not to make political statements.

The task before the jury was exclusively to weigh the facts of the shootings and measure whether they amounted to guilt under Wisconsin laws. It was not the jury’s place to determine the wisdom of those laws, or the case’s place in the larger debate over policing, race and politics.

Friday’s verdict ends Rittenhouse’s trial, but not the nation’s. More verdicts are due soon — in the trial in the killing of Arbery, in a civil case involving the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” protest in Charlottesville, Va., and more. The path toward justice is a rocky one.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.