Op-Ed: The hunger strike against school closures is also about everything else that ails Oakland

Two educators in Oakland began a hunger strike Feb. 1 with a specific objective: to halt the closure and consolidation of neighborhood schools in majority-Black areas. They put their bodies and their long-term health on the line for the community. I am the physician coordinating the medical response to ensure these educators, André San-Chez and Moses Omolade, are as safe as they can be.

But no one can be very safe in the flatlands of Oakland, a place that accumulates the worst of toxic exposures in the Bay Area. I hope that the hunger strike will draw attention not only to decisions about certain schools, but also to the larger forces that pushed Black and brown people into less desirable spaces and that subject them to highly toxic air pollution from the combination of industry, freeway traffic and idling diesel ships at the Oakland port.

One’s ZIP code is eerily predictive of a person’s lifespan. The sum of a lifetime of exposures is called the exposome, and when it comes to chronic inflammatory disease — which makes up the largest share of disease I treat as a hospitalist at UCSF — the exposome is more predictive than our genetics. If the exposome around us is toxic — full of not only air pollution, but also racist police violence and legacies of intergenerational trauma — our immune systems respond with chronic inflammation. This is why diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease and depression — all chronic inflammatory diseases — are more prevalent in socially oppressed people.

Oakland illustrates the point. Racist lending practices in redlined neighborhoods of the 1930s have real impacts that continue today. Less money went into these communities so there are fewer parks, fewer trees and an abundance of pavement, leading to higher temperatures than in well-resourced neighborhoods. Street violence thrives, and healthy food options are hard to come by. It’s a recipe for chronic inflammatory disease and diseases like COVID-19.

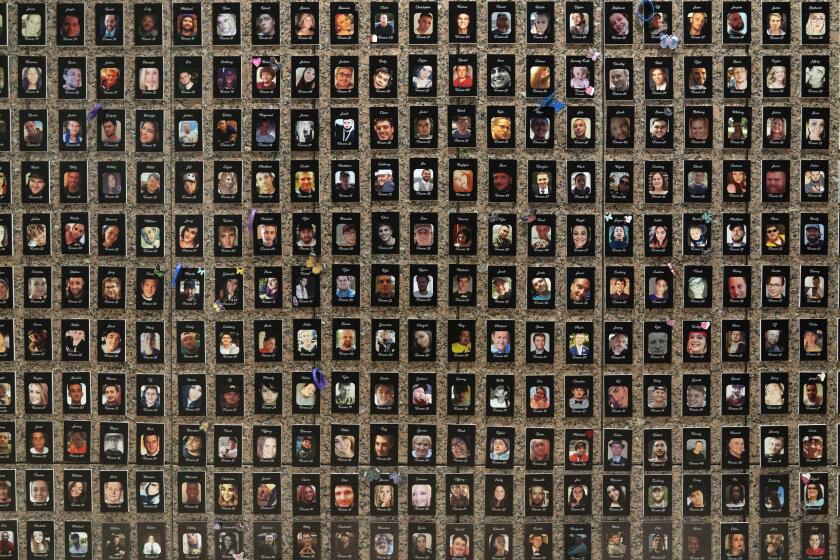

People who live and work in these areas already know this. When I asked San-Chez why they went on a hunger strike to protest school closures, they replied: “I chose it to show it through my body, because as I begin to waste away, so do these communities. I wanted a physical manifestation of what it looks like to these Black and brown communities that are being divested in.” What happens in the body happens in the world around us, and what happens in the world around us leaves sediments in our bodies.

The political, social, historical, ecological and biological are all interwoven, and this is starkly clear as I watch San-Chez’s eyes become more sunken as their body mass index dips into the critical zone. By day 20 without food, the glucose stores in the liver have been used up. The body has metabolized fat, and it now goes for the muscles — from the arms and legs and even from the heart — to keep glucose levels in the blood available for the brain to continue its critical functions. This stage is where long-lasting damage from a hunger strike sets in. Over the past week, San-Chez has been experiencing chest pain.

Losing a neighborhood school is like starvation for a community. The buildings that once were a hub of social life become places for urban blight. Single-parent families that are already stretched are forced to travel farther to newly assigned schools. Children lose critical connections with neighbors, teachers and administrators who have become trusted people invested in their growth.

When California has a budget surplus with $20.6 billion unspoken for, it’s time to start pouring resources into those communities that have been historically harmed through decades of divestment. Maintaining neighborhood schools is a start. We must also think bigger, to build exposomes that will create the opportunity for health for all.

Rupa Marya is an associate professor of medicine at UC San Francisco and a co-author with Raj Patel of “Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.