Why teaching fifth-graders about Presidents Day was always my favorite day

- Share via

Every year right before Presidents Day I’d try my best to gauge my fifth-graders’ knowledge about the holiday. And every year my educational wards never failed to enlighten me. Most of what they thought they knew was wrong. Much of it was highly entertaining. But that is the mortar and sticky glue of fifth grade.

First of all, most 10-year-olds have absolutely no idea about historical chronological time. A few would know George Washington was the first president, but that was about it. The year 1776 meant nothing. If my students were acquainted at all with Washington and our 16th president, Abraham Lincoln, more than one assumed they were best buddies who flew kites together with Benjamin Franklin.

One year, I asked my class to write on the board what they knew about Washington and Lincoln. And their final collective conclusion was a jumble of chopping, log cabins, an ax, cherry trees and lies. One child said he thought one of the presidents was a lawyer, so he probably lied. The class concluded Washington probably chopped down cherry trees with an ax to make a cabin for Lincoln.

A teacher gives a St. Patrick’s Day history lesson to his fifth-graders. His students respond with rapt attention and charming observations.

I did my best to straighten all this out, using timelines, and mentioned that some of the stories about the presidents were myths and then, of course, explained that a myth was a tall tale.

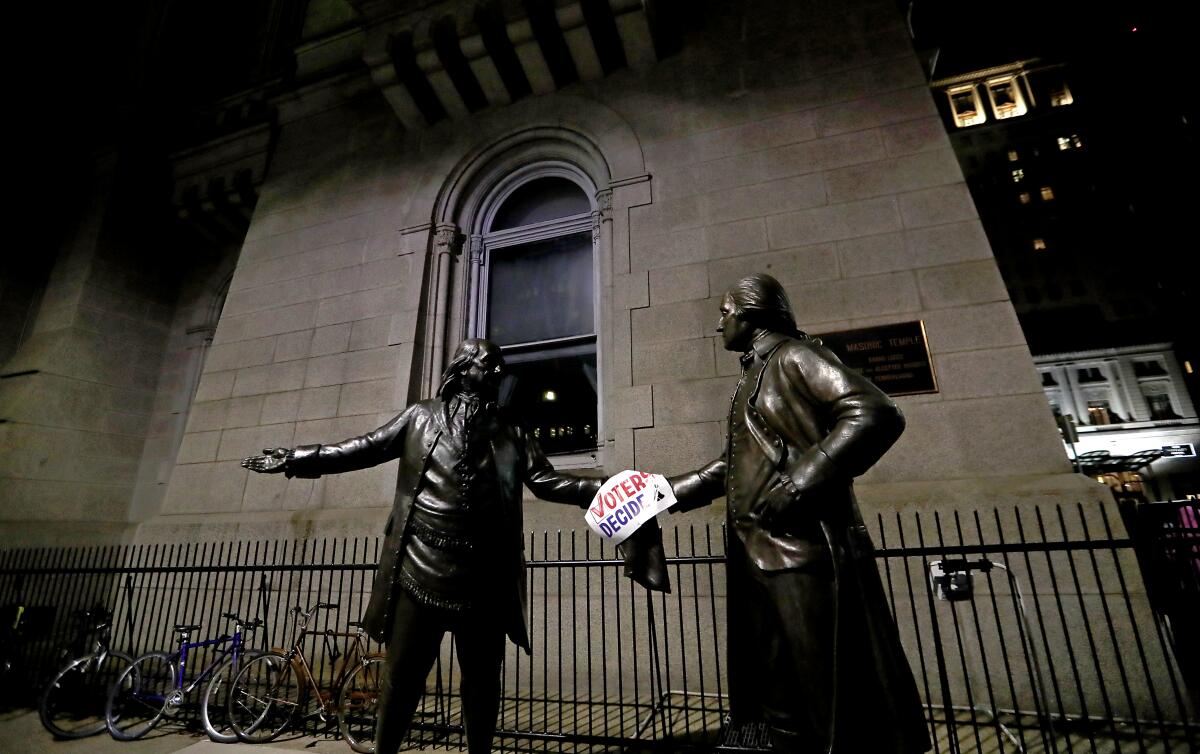

Then I’d try to slip in some fact-based history: I pointed out that after the Americans barely won the Revolutionary War, George Washington was so popular people wanted him to be king of America. And he said no, which was an amazingly honorable thing. He preferred to be president for a short period of time and then go home to a private life and have an election across the whole country so people could choose another person. Sadly, enslaved people, women, Indigenous people, non-landowners and fifth-graders could not vote. But on this day, we would make up for those many slights by having a mock election.

One student, Jose, raised his hand. A large frown covered his face. “Well, teacher, I don’t like Presidents Day this year. I hate it.”

That confused me. “I’m sorry to hear that. I mean we get the day off from school out of respect for these two presidents,” I said. “One of them was even assassinated — shot to death.”

“So,” I asked Jose, “why do you dislike Presidents Day so much?”

He buried his head in his arms. No words came from him. However, his BFF filled in the details.

“Teacher,” his friend informed us, “Jose got ripped off.”

The goofy, confused-teacher look must have crossed my face. “How is Jose,” I asked, “cheated by Presidents Day?”

His friend said, “This year it’s Jose’s birthday too. And all the stores have pictures of the presidents but not of him. He thinks it’s not fair. His sisters bug him about it.”

Jose had a point. How could he compete with a president?

“Hmm, that doesn’t seem fair, at all,” I said. “I’ll tell you a secret about my birthday if you don’t tell anyone.”

Now I had their attention. Even Jose popped his head up from his desk.

Contributor: The issue of gun violence often invaded my 5th-grade classroom. Here’s how I handled it

The teacher would confess he’d shot a pistol as a child, then ask his fifth-graders: “How many of you know of guns in your homes?”

“My birthday is September 1st,” I said. “So when I went to kindergarten in September, I was barely 5 years old. School started on my birthday. I was the smallest and youngest in the class. I ended up staying back in first grade to catch up.”

Their collective eyeballs bugged out.

With shock a child blurted, “You can’t stay back, you are the maestro!”

“Teachers can stay back,” I replied.

Another child suggested, “I think maybe Teacher Snider stayed back too. I don’t like him.”

“No, Mr. Snider didn’t stay back,” I replied. (His name has been changed to protect the innocent and the guilty.)

Another child pointed at me and said, “You are telling a Pinocchio, teacher!”

“I’m telling the truth. I repeated first grade, and things aren’t always fair.”

Heads shook with disbelief. I’d shattered their educational world. Assuredly it would be discussed at dinner tables across Castroville later that day.

“OK, OK,” I said, trying to bring them back before introducing what was always the high point of the day — a mock election.

“You can vote for George Washington, Abraham Lincoln or even write in the name of a candidate,” I said. And then I had to explain what that meant.

We voted, we tallied up all the ballots, even the handful of write-ins. I so hoped Jose would beat Washington and Lincoln. He didn’t.

The outcome was pretty much the same as it was every year. Teacher Paul Karrer, president for the rest of the day, making Presidents Day my favorite day. Life is not fair.

Paul Karrer is a writer in Monterey, Calif. He taught fifth grade in Castroville for 27 years.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.