Column: How would you feel if you lost $55 billion? Would you still buy that superyacht?

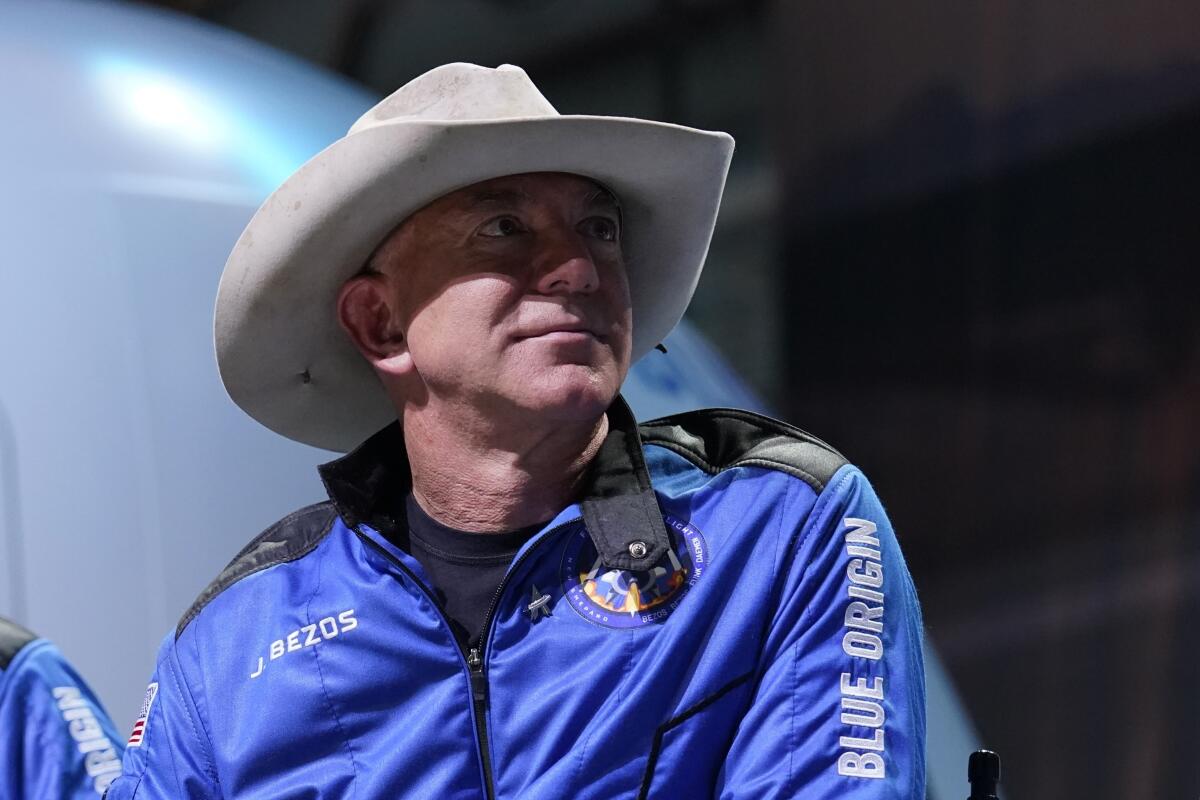

Elon Musk has lost $51 billion since the beginning of the year. Jeff Bezos has lost $55 billion.

Mark Zuckerberg lost more than half his fortune — $64 billion, as of Saturday — and plummeted to No. 17 on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Call me old-fashioned, but in my world tens of billions of dollars still sounds like a lot of money. So I briefly, almost, kinda felt bad for some of the world’s richest people.

But then I snapped out of it. What was I worrying about them for? No matter what happens to his portfolio, Musk isn’t going to have to take on a second job. Even at No. 17 on the billionaires’ list, Zuckerberg isn’t going to struggle to cover his rent or pay his hospital bills.

In fact, as far as I can tell, Bezos won’t even let his stupendous multibillion-dollar losses derail his plan to buy the world’s biggest superyacht, a 417-foot-long behemoth sailing vessel that is reportedly going to cost him more than $500 million. The yacht made news last week because it is so tall it can’t sail under the bridge in Rotterdam, Netherlands, it must pass to reach the open sea.

What kind of world do we live in where people with unimaginable fortunes build half-billion-dollar pleasure boats while more than 730 million other people subsist on less than $1.90 a day?

Worse yet, Bezos, Musk and the rest of America’s hyper-rich often pay a lower effective tax rate than the rest of us — and sometimes pay nothing at all. Bezos, for instance, didn’t pay a penny in federal taxes in 2007 and 2011, according to a ProPublica investigation. Musk didn’t pay any in 2018.

One reason I’ve been stewing about this subject is that even as the stories about Bezos’ yacht were coming out, I also happened to be reading an old, yellowing book I’d randomly pulled off an upper bookshelf — “Looking Backward, 2000-1887,” a once-famous socialist utopian novel by Edward Bellamy first published in the late 1880s.

“Looking Backward” was an enormous bestseller when it came out, an early example of speculative futuristic fiction, preceding H.G. Wells’ “The Time Machine” by about seven years. It tells the story of Julian West, a 19th century Bostonian gentleman who is put into a hypnotic trance to fight his insomnia — and wakes up 113 years later in the year 2000. To his amazement, West learns that almost all the world’s great social problems have been solved.

In 21st century Boston, it seems, there’s no poverty.

There are no more wars, because mankind has realized that nothing is worth fighting against except “hunger, cold and nakedness.” Crime, labor strife, corruption — they’re all gone, because there’s no longer any motivation for them. A society has been built instead on “mutual benevolence and disinterestedness.”

There are no prisons, no jails, no lawyers.

Income inequality, the defining characteristic of the so-called Gilded Age in late 19th century America when West went into his trance, has been eradicated. As in all socialist utopias, everyone is fed, housed and cared for according to his or her needs. No special perks for the Carnegies, Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Zuckerbergs, Bezoses or Musks.

OK, OK, the book is ludicrously naive. Downright silly, really. It lectures interminably; it is self-righteous and starry-eyed. And its vision of the future is just flat-out wrong.

The intervening 20th century between when Bellamy wrote it and where we are today was one in which idealism took a beating; for much of the time, fascism, totalitarianism and mass murder were ascendant. Utopianism seems far-fetched to us now.

Bellamy may have read Marx but he knew nothing of Stalin.

Still, it’s awfully sad, isn’t it? Sad that more than 130 years after the book was published we’re still facing so many of the same problems Bellamy believed, or perhaps hoped, would be long since solved.

Sure, people in the aggregate are no doubt better off today than they were a century ago. War is less common, life expectancy is longer, and fewer people are mired in deep poverty.

But inequality has been making a comeback. Instead of the Golden Age of mutual benevolence that Bellamy foresaw, we have 161,000 homeless people in California as of the last count. One-third of the state’s residents live in or near the poverty level. At the same time, California also is home to 186 billionaires, according to Forbes — more than any other state in the country.

In America today, a shocking number of families say they would have difficulty finding $400 to cover an emergency expense. Many people can’t get sick without fearing they’ll go bankrupt. Ambitious students rack up tens of thousands of dollars in debt trying to educate themselves. Wages are stagnating and prices are climbing.

Yet Bezos’ yacht is so big it can’t fit under the 95-year-old Koningshaven Bridge in Rotterdam. So the yacht makers had the chutzpah to ask the city to dismantle a portion of the bridge to let it through. The resulting public uproar persuaded the ship’s builders not to formally apply for a permit.

I’m not recommending confiscating the fortunes of billionaires, Edward Bellamy-style, to build a socialist paradise. But I certainly favor far higher taxes on the likes of Bezos and Musk, and putting that revenue to work solving society’s problems.

It’s not much of a spoiler to reveal that by the end of “Looking Backward,” Julian West fervently hopes that he will continue to live in the glorious future and not be returned to the dismal past.

But I wonder if he were to awaken in the United States today as it really is, if he wouldn’t want to catch the first boat — maybe Bezos’ boat? — back to the 19th century.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.