Why inappropriate books are the best kind

- Share via

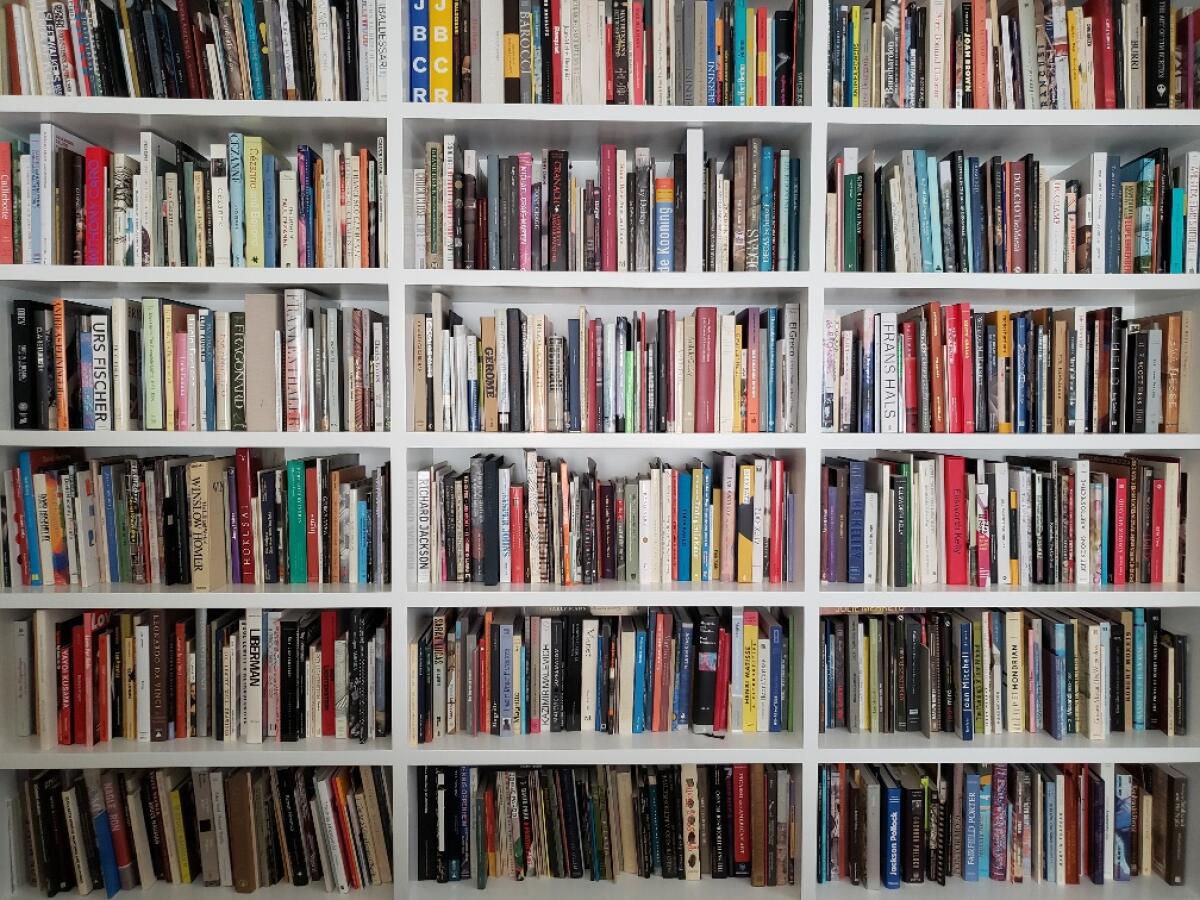

The house where I was raised had an open shelf rule. This meant my brother and I were allowed to read anything, no matter how inappropriate or beyond our years. We never had to ask.

I spent hours of my childhood perusing the volumes on my father’s bookcases at will, trial and error. Histories, thrillers, science fiction, books on politics and culture — all of it was available to me.

I keep thinking about this as more and more school districts participate in what is shaping up to look like an open war against reading. According to “Banned in the USA,” a report issued by the writers’ organization PEN America in April, nearly 1,600 individual books were banned in 26 states between July 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022.

Among the titles challenged or removed are Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me,” Elizabeth Acevedo’s “The Poet X,” Roxane Gay’s “Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body” and Robin Benway’s “Far From the Tree.” All are works of abiding literary merit that address issues of identity and race and family — in other words, exactly the kinds of books students should be reading now.

Although the challenging of books and curriculum is hardly new in the United States, what we’re facing now is somewhat different. Of the current bans, PEN notes, “41% (644 individual bans) are tied to directives from state officials or elected lawmakers to investigate or remove books in schools.” It is not parents or even school boards driving many of these challenges. It is the power of the state.

L.A.’s authors, from 19th century novelists to Wanda Coleman to Steph Cha, have always pushed genre boundaries and dissected California myths.

That represents, says PEN, “an unprecedented shift.”

I take it for granted that books are good for us. Countless studies have reinforced what many recognize from experience: Literature encourages compassion. As Jane Smiley wrote a decade ago in the New York Times: “Reading fiction is and always was practice in empathy — learning to see the world through often quite alien perspectives, learning to understand how other people’s points of view reflect their experiences.”

At the same time, there’s more to reading than learning to be a better person. Books are not vegetables, after all. We don’t read them for the same reasons we take vitamins, or eat healthy meals. Part of the joy of reading — its essential fiber, if you will — is the way it can disturb us, disrupting our preconceptions and easy pieties. Part of what books do is to show us who we are or might become.

I know this from my open-shelf experiences. Often, the more inappropriate or beyond me a book was, the more intensely I was drawn to it. I count myself lucky that I was surrounded by adults willing to let me find my own level — not just at home but also at school. In third grade, the school librarian, who already knew me as a precocious reader, didn’t stop me from taking out “War and Peace,” which I kept for a week before I returned it, unread.

It was not only the reading, in other words, that was important but also the permission to do it widely, indiscriminately. That freedom left me feeling respected, affirmed. And it led me, by my early teens, to “inappropriate” writers that in the end couldn’t have been more appropriate: among them, Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller, Sam Greenlee and Philip Roth.

Vonnegut taught me the universe was absurd; Heller, that authority deserved to be ridiculed. Greenlee, in his novel “The Spook Who Sat By the Door,” revealed the hypocrisy of race in America. And Roth — well, perhaps the best way to explain it is to say that, in “Portnoy’s Complaint,” he portrayed male adolescence, which I was then experiencing, in the most visceral and outrageous terms.

The jacadranda, a transplant like so many of in Los Angeles, and an essential emblem of the city.

Writers like these represented a gateway to other authors and narratives. Vonnegut led me to Samuel Beckett, Greenlee to James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka. From Heller, I moved on to Terry Southern and William Burroughs. And “Portnoy” prepared me for the magnificent “Fear of Flying” by Erica Jong.

Reading such books as I found them helped me to reckon with the complexities and contradictions of the adult world. More important, by thinking alongside their authors, I began to think for myself.

This, of course, is what the book banners object to, that readers might be influenced by ideas that legislators, parents, the neighbors down the block don’t like.

PEN sees the issue through the lens of the 1st Amendment, which is valid, especially given the actions of so many lawmakers and the effects on so many constituencies. But I don’t want to overlook that other lens — of curiosity, self-knowledge, possibility, inquiry. Literature gives us language by which to know ourselves.

But in order to do that, it has to be available. It has to remain on the shelves. Where would we be without inappropriate reading? Ask any reader and they’ll tell you: We would be lost.

David L. Ulin is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.