Why the Trump indictment isn’t as legally dubious as many claimed

- Share via

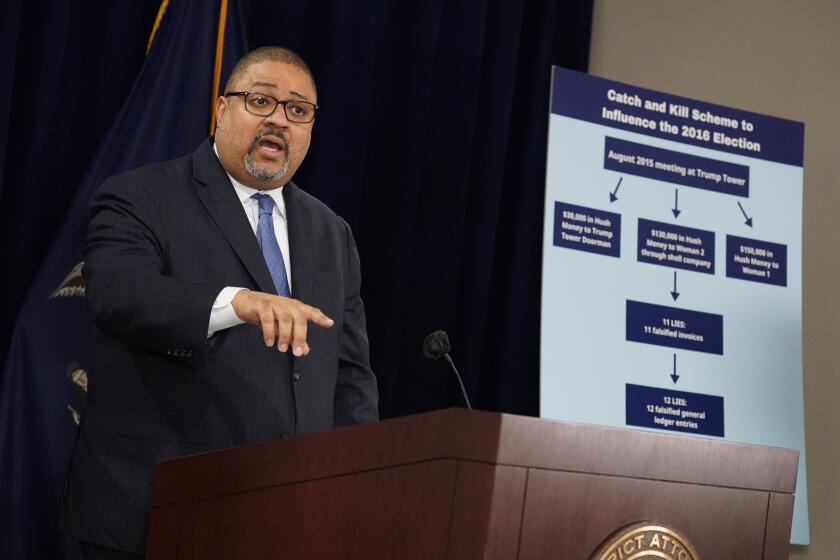

Even before the unprecedented indictment of former President Trump, Manhattan Dist. Atty. Alvin Bragg was widely accused of relying on a dubious legal theory. Many observers said the idea that a New York grand jury could charge Trump with covering up a federal crime was untested. They were wrong.

In the days before the indictment, some legal analysts warned that New York lacked jurisdiction to charge Trump with efforts to hide federal crimes such as illegally financing and influencing the presidential election. Bragg was criticized across the political spectrum for trying out a novel legal theory in a historic indictment. Even those hoping to see Trump held accountable were concerned that the questions surrounding the case could exacerbate national polarization.

When the indictment was unsealed, sighs of relief greeted the revelation that Trump could also be charged with concealing state tax crimes, which are well within Bragg’s jurisdiction. But the fact is that Bragg is on solid legal ground in accusing the former president of covering up federal crimes, too. There is nothing remotely novel about charging a defendant in one jurisdiction for trying to commit a crime in another.

The Manhattan district attorney pointed to new evidence that the payment to Stormy Daniels was meant to break campaign finance and even tax law.

Take the 1894 case in which two men, William Hall and John Dockery, fired shots from North Carolina across the border into Tennessee, where the bullets struck and killed someone. They were convicted of murder in North Carolina, but the conviction was overturned on the grounds that the killing took place in Tennessee, where they should have been brought to trial.

But what if Hall and Dockery had missed? In that case, the court made clear, North Carolina would have been within its rights to prosecute them for attempted murder. The attempted crime can take place in a jurisdiction other than the one that would rightly prosecute if the attempt were successful.

Or consider a much more recent case in New York. In 2009, Theophilis Burroughs took a deposit from undercover New York police officers and agreed to meet them in South Carolina, where he would sell them illegal guns. Had the plan been completed, Burroughs would have violated South Carolina’s gun laws, not New York’s. On these grounds, Burroughs claimed that New York had no right to prosecute him for the attempted illegal sale.

But a court rejected his argument. If you try to break South Carolina’s laws in New York, the reasoning went, you are committing a crime in New York: the crime of the attempt.

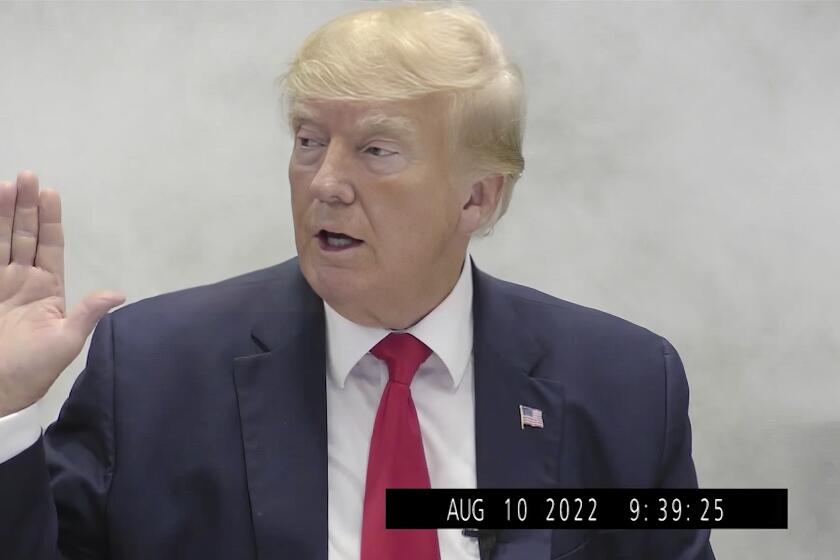

Cases brought by Alvin Bragg and E. Jean Carroll put the ex-president in the impossible position of having to take the stand to make much of his case.

Trump, likewise, is not charged with successfully influencing a federal election. That would require showing that the election would not have proceeded as it did if he had not paid hush money to Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal, which would be a very tall order. Trump may well have won in 2016 even if Daniels and McDougal told their stories before the election. If success would have required flipping the election his way, there would be at least reasonable doubt about such a charge.

Trump is really being charged with an attempt to illegally influence the election. To prove Trump is guilty of the crimes he is charged with, Bragg needs to show he was trying to hide something illegal by falsifying business records. And the crime Trump tried to commit that way need not be a crime in New York. That is, it’s as if he fired a shot across the border and, for all anyone can tell, missed.

This isn’t to say we know how the case will turn out. People with the money to hire first-rate defense attorneys are regularly acquitted of quite ordinary charges. And judges are sometimes moved by specious arguments to the effect that ordinary charges are extraordinary.

But there is nothing extraordinary, much less new, about being charged with attempting to commit a crime in the jurisdiction where you made the effort — even if the successful crime would have taken place elsewhere.

Gideon Yaffe is a criminal law professor and a member of the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School. He is the author of “Attempts: In the Philosophy of Action and the Criminal Law.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.