- Share via

Monday is the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. Now, when the country is awash in divisiveness, fear, anger and incoherence, the message of hope delivered Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial challenges us to remember the courage and tenacity of those upon whose shoulders we stand.

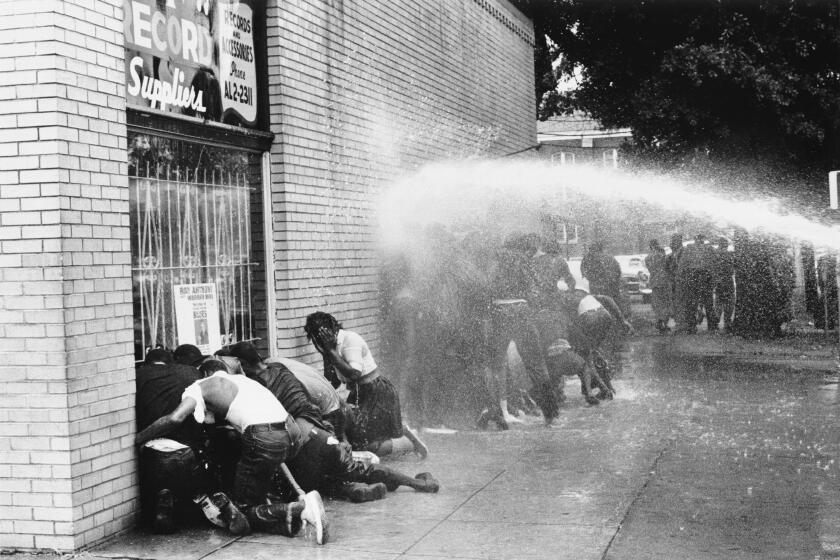

The decade of the 1960s was as turbulent as the 2020s — in some ways worse. Racism then didn’t even try to hide behind innuendo. Those were the days when police trained fire hoses and dogs on children, when grown-ups spewed slurs at Black teenage girls, in brand new dresses and with freshly done hair, as they entered formerly all-white schools, and when four little girls were killed in a fire-bombed church.

And yet, people of good intention, from all backgrounds, did not give up. They persevered in the fight for justice. The midweek march brought 250,000 Americans to Washington — young, old, rich and poor, the descendants of those who survived the Middle Passage, enslavement, segregation, the Holocaust, the Trail of Tears, the potato famine and the tyranny of kings, queens and autocrats. They stood together to protect the idea enshrined in the declaration that “all men are created equal.”

Keenan Anderson, cousin of a BLM founder, is among three men of color who have died this year after encounters with LAPD officers. A vigil was packed.

My uncle, Whitney M. Young Jr., then the executive director of the National Urban League, was one of the organizers of the march. When he spoke that day, he paid tribute to the protesters, and he shamed those who stood in the way of equal rights.

“We must remind the indifferent,” he told the multitudes gathered on the National Mall, “and we must warn the opposed. Civil rights, which are God given and constitutionally guaranteed, are not negotiable in 1963.”

I made a documentary about my uncle because I needed to understand what motivated him. He grew up in Jim Crow America, risked life and limb in a segregated U.S. Army in World War II only to return to a country that wouldn’t let him drink a cup of coffee wherever he wanted. How does one do that without descending into anger or despair?

I discovered Uncle Whitney learned at an early age that character and determination were essential. As a teenager in 1930s Kentucky, Whitney and his Black basketball teammates were refused service at a local restaurant following their championship victory. He was furious. His father — my grandfather, Whitney Young Sr. — told him, “Son, never let anyone drag you so low as to hate them. Because you only hate that which you fear, and I want you to fear no man.”

The short answer is probably not. But the movement is 10 years old and, after several controversies, public opinion is down. Some want a new strategy.

Granddaddy made it clear that Whitney’s humanity as well as his survival were contingent upon his understanding that connection. It was a lesson that served him well.

Whitney Jr. became one of the “Big Six” civil rights leaders in the country. He played a major role in gaining support for the March on Washington from corporate America, the middle class and a reluctant President Kennedy. Adept at persuading the powerful to do the right thing, he deserves credit for helping to push the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965) through Congress, and for being the architect of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty.

I try to summon my uncle’s grace and perseverance now, but it’s hard. Some of our most prominent public officials shamefully denigrate swaths of people — Latinos, Black people, women, Asians, the LGBTQ+ community. And there have been consequences. The California 2022 hate crimes report showed a 20% increase from the previous year.

With Melina Abdullah and Patrisse Cullors playing key roles, Black Lives Matter has transformed from a small but passionate movement into a cultural and political phenomenon.

We have many times thought we were beyond all this only to be disappointed. African Americans were emancipated after the Civil War only to later be subjected to deep and lasting segregation. Black, Native American and Japanese American soldiers wrongly believed service to the United States would win them acceptance by the majority population. In the early ’60s, there was a chant, “We’ll be free by ’63.” We weren’t.

And then there was the election of President Obama, when the hopeful and the naive declared our country was “post-racial.”

But the dog whistles of racism keep coming back with a vengeance, and now the guardrails of democracy — the right to vote and the institutions of government — are challenged.

How do we break the cycle and truly advance?

Let’s start by affirming our shared values. Do we believe that all of us are equal and entitled to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”? There are forces, domestic and foreign, that are willing to sow seeds of chaos by using the transparent technique of divide and conquer. But what do we the people want, and can we unite around this vision? We must decide.

When Martin Luther King Jr. needed funds for Project Confrontation in Birmingham in 1963, Harry Belafonte made it happen.

Next, to ensure that we do not succumb to schemes of the greedy and ambitious, we need more education, not less.

America’s disinformation crisis began at its founding, when the land of the First People was seized and when Africans were imported, enslaved and bred as cheap sources of labor. To justify these actions, the fiction arose that Native Americans and Black people were “others,” not really human, that they were stupid, lazy and, above all, to be feared.

This nonsense persisted. In 1890, a dean of sciences at Harvard University, Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, wrote this about slavery, “The discipline of orderly, associated labor, though the activities were limited, had a civilizing influence, for it tended to subjugate the passions of the savage.”

Still today we hear a presidential candidate suggest that enslavement was beneficial because it taught Black people skills like blacksmithing. Clearly, this man was never taught that forging iron was evident in West Africa as early as the 6th century BC.

White people shouldn’t just pat themselves on the back for being less terrible than the crowd that attacked a lone Black man on Saturday.

We desperately need inclusive education in our history as an elixir against the poison of ignorance and bigotry. It is not about guilt. It is not about hating America. It is about facts and the need to own up to and address our mistakes so we can move toward a better future.

As we remember the March on Washington, we can learn from my uncle and his father’s counsel to never let anyone drag us so low as to hate. In the words of my friend and colleague Pastor James M. Lawson, now 94, a hero of the 1960s civil rights movement, “We must not allow our humanity to become deformed.”

We build our precious democracy together day by day. Now it is time to transform the “dream” Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of so eloquently 60 years ago into something stronger, a vow to never give up until America, in word and deed, becomes the nation of our hopes and expectations.

Bonnie Boswell is a reporter and producer. Her film “The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights” was shown at the White House on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. “Bonnie Boswell Reports” is the lead-in to “PBS Newshour” Fridays on KCET/PBS and at PBS.org.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.